Hyman Bloom:

A Survey of Works on Paper

by Robert Alimi, © 2024

As one of the most technically gifted draftsmen of the 20th century, his drawings hold their own against any in history. They are masterworks, in which volume, shading, light, and line are brilliantly communicated.

“Hyman Bloom: Landscapes of the Mind” exhibition introduction, MFA Boston, 2024

- Drawings by Hyman Bloom by Bernice Davidson, 1957

- Eight Drawings by Hyman Bloom by Hyman Swetzoff, 1962

- The Drawings of Hyman Bloom by Marvin Sadik, 1968

- Hyman Bloom: The Lubec Drawings by Philip Isaacson, 2001

- The Drawings of Hyman Bloom by Sigmund Abeles, 2002

- Hyman Bloom: A Survey of Works on Paper by Robert Alimi, 2024

This essay provides an overview of Hyman Bloom’s lifelong engagement with works on paper. The illustrated works cover the 80 year period from 1926 through 2006.

Bloom is particularly admirable for a lifetime spent fully developing his natural gifts as both a draughtsman and a painter. Never squandered any of his innate talent, he devoted himself to pursuing a continual path of growth as an artist, both in terms of vision and technique, from the age of 13 until his passing in 2009 at the age of 96. He was a multicultural artist who drew inspiration from both Eastern and Western art, and as much from the art of the 16th century as from the art of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. An examination of his works on paper provides an especially interesting way to follow his lengthy and fruitful artistic journey.

Known as an artist whose exploration of a particular subject would often result in a complete series of paintings, his drawing work shows a similar approach, both with subject matter and with medium. He would sometimes consider a singular subject through the lens a varying mediums, while at other times employ a single medium (e.g., white ink) and apply it to multiple themes.

The first museum exhibition entirely dedicated to Bloom’s works on paper took place in 1957. Organized by the curator Bernice Davidson, the exhibition featured 35 drawings and traveled from the Currier Museum in Manchester, New Hampshire to the Museum of Art at the Rhode Island School of Design before finishing at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Connecticut.

A subsequent museum exhibition of works on paper took place in 1968. Organized by Marvin Sadik, this exhibition featured 44 works and traveled from the University of Connecticut Museum of Art to the San Francisco Museum of Art before finishing at The Whitney Museum of American Art.

It’s unfortunate that the catalogs of these two Bloom drawing shows were printed in black and white. Lost were the subtle variations in the red and brown conte crayon works and the rich, almost velvety, texture of many of the charcoal works, as well as the color introduced through the use of dark toned colored papers used with white ink drawings. The majority of the works included in the galleries of this essay are improved images over what has been published previously.

Throughout his career, Bloom included a variety of materials and techniques, including the following:

- Graphite

- Charcoal

- Silverpoint

- Conte crayon

- Ink (black, white & sepia)

- Gouache

- Monotype

- Monoprint

- Etching

- Pastel

- Watercolor

Bloom was open to experimentation with both materials and techniques; for instance, his use of dissolved conte crayon applied with a pen. Another example, as recalled by Bloom’s first wife, the artist Nina Bohlen, was his use of an electric vacuum to reduce the density of charcoal in areas of charcoal works.

In a 1958 article1 published in the Studio Talk column of ARTS magazine, Bernard Chaet discussed Bloom’s variety of materials and techniques. Chaet wrote:

For one who pursues so many different drawing methods, theories which separate drawing and painting into various categories are of little concern. When pressed for definitions he simply described drawing as "forms without color." Drawing, then, as practiced by Hyman Bloom, is a separate discipline. He has developed personal techniques which have expanded his visual vocabulary. He works both in a graphic manner -- showing each tool mark constructing the form -- and in a tonal manner wherein the blending resembles painting. And although he works with many different techniques, his drawings contain the same symbols which have long been identified with his paintings.

Bernard Chaet, March, 1958

This essay follows Bloom’s career chronologically with sections organized largely based on the Bloom chronology included in Modern Mystic: The Art of Hyman Bloom:

As with his paintings, Bloom was never overly concerned when it came to the titling of works on paper: many landscapes are simply titled “Landscape” and most rabbi portraits are simply called “Rabbi with Torah”. This creates challenges when cataloguing the works. For example, there are four different drawings previously exhibited as “Landscape 2” — from 1957, 1958, 1962 and 1970. Thankfully, they are of distinctly different sizes and materials.

Some of Bloom’s drawings are initialed, some are dated, many have no signature or date. The exception is the series of charcoal landscapes completed between 1962 and 1967, but even in this case there are some inconsistencies in the sequence numbers.

There are a total of 17 embedded image galleries throughout this essay illustrating over 100 works. To view higher resolution gallery images in a slideshow format, click on any of the images included in a gallery. The galleries in each section generally group works by materials or subject matter. The selected works for each section show Bloom’s proclivities towards materials and/or subject during a given time period. While he may have had a predominant focus on a particular medium at a point in time (for example gouache or charcoal) he would concurrently produce sketches and studies, most often in ink or conte crayon.

Student Years & the Zimmerman Method (1926-1933)

In 1926, Mary Cullen, Bloom’s eighth grade art teacher at Washington Junior High School, successfully recommended him for a scholarship to attend after-school classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. At Cullen’s suggestion, he also enrolled in drawing classes at the West End Community Center, a settlement house on Blossom Street. The instructor at the settlement house was Harold K. Zimmerman (1905–1941), whom Bloom later described as a “hero figure.” Bloom remained Zimmerman’s devoted pupil for the next seven years.

Harold Zimmerman was just 20 years of age and a student at the Boston Museum School when Bloom became his student.

Born in New York City in 1906 to parents Samuel and Lena, by the time he was five, the family had moved to Malden, MA. One of his four siblings was his older brother Isadore, who in 1950 commissioned the Frank Lloyd Wright “Zimmerman House” in Manchester, NH, now owned by the Currier Museum and open to the public.

In her dissertation, art historian Judith Bookbinder quotes Bloom describing Zimmerman as “a teacher of almost military discipline” who instituted “an exacting training procedure of drawing from memory after intense observation.”2

Zimmerman’s unique approach to art instruction is discussed in Denman Ross‘s “An Experiment in Art Teaching” , a 1930 proposal to gain funding from Harvard University for support of Zimmerman’s teaching of Bloom and fellow student Jack Levine.

The whole problem of art teaching is involved in Zimmerman's experiment and a solution of the problem will be not only interesting but may be far reaching in its consequences.

Denman Waldo Ross, February, 1930

In his proposal, Ross included images of drawings by Bloom and Levine with notes on each drawing (Bloom’s drawings along with the associated comments can be viewed here). Ross never received his requested funding, but continued to pay out of his own pocket to keep the project going for another 3 years.

Another resource on Zimmerman’s method is the journal of her studies with Zimmerman kept by Rosamund Pickhard 3 covering the period between October, 1936 and May, 1938. Also, raw footage from the Bloom documentary “The Beauty of All Things” includes a 35 minute segment by Nina Bohlen showing her progress through the Zimmerman method while a student of Bloom.4

Hyman Swetzoff briefly described the Zimmerman method in a 1962 article for The Massachusetts Review5:

The method evolved by Zimmerman was based on a series of physical rhythms: the hand, following its natural movements, rhythmically traced with a hard pencil on paper what looked to be a giant spider's web. From this the imagination took over to perceive in the linear patterns, figures and landscapes, the subject which the pupil was to develop. As the hand became more controlled and proficient, the imagination, with the aid of observation and memory, formed more specific concepts until the maze of lines disappeared into the total idea. And a picture was produced. At that period, the drawings of these students were very much alike. But in a very short time, an amazing development could be seen in each one. The differentiations that occurred were those of touch and, increasingly, as the imagination took hold, of personality.

Hyman Swetzoff, 1962

With Zimmerman as his instructor, Bloom’s draughtsmanship and composition skills advanced rapidly.

By the age of 16 his subject matter included genre scenes and a heavy dose of mythological beasts and figures. His most well-known juvenile work is certainly “Man Breaking Bonds at Wheel” (gallery 1, first image). A close look at the drawing reveals the name “Hyman Bloom” on the figure’s belt along with the name “Robert Reilly(?)” written on the right leg shackle. It would be interesting to learn what Robert’s relationship was to the young Bloom.

Drawings from this time are often both verso and recto, with some works featuring a series of smaller studies on one side with the larger completed drawing on the other. Some of the earliest works have mechanical drawing homework assignments on their back. I’ve not seen any with Bloom’s own name on the assignment — he apparently would scrounge graded and returned assignments from fellow classmates at Boston’s High School of Commerce, since the paper was of good quality.

By 1929/30 Hyman had become more intently focused on the human figure. Wrestling and boxing scenes came to dominate his subject matter. The Fogg Museum at Harvard holds a good number of these early Bloom drawings, many having been donated by Denman Ross.

Gallery 1

Student Works (1926-1933)

In 1961, Art in America featured Bloom in the first of a series of “portraits” of contemporary artists. In his article, Art in America editor Brian O’Doherty wrote:

Bloom’s early drawings under Zimmerman are young master drawings and, like the glass flowers at the Peabody Museum, they are among the major Boston phenomena. They are incredible achievements for a young boy with resilient sureness of line and a facility that is breathtaking.

Brian O'Doherty, 1961

The period of 1926 through 1933 was an incredibly fruitful time for Bloom. His skillset had grown remarkably and under the guidance of Zimmerman, whose approach to picture making was entirely logical to Bloom’s way of thinking, he had developed all the tools he needed to strike out on his own. He now needed to develop his unique voice as a visual artist.

Exploring Themes (1934-1938)

In 1933, having a conviction that his student days had reached their end, Hyman broke with both Denman Ross and Harold Zimmerman. Needing studio space, he started sharing a studio with two close friends, Jack Levine and Betty Chase. Bloom lived in the unheated studio except during periods of bitter cold, when he moved back in with his parents.

For financial support he signed up with The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and when that program ended, he moved on to the Works Progress Administration (WPA). He would drift on and off the WPA’s roster of Boston easel artists until 1941.

He continued his work with themes that featured the human figure — particularly figures in motion — including a series that he referred to as his “circus pictures”. The circus pictures typically featured equestrian acrobats and trapeze artists. Gallery 2 shows some representative works from this period.

Gallery 2

Theme Exploration (1934-1938)

By the end of 1939, Bloom had found his own voice as a painter, starting with his series of four powerfully expressive Christmas Tree oils. In 1942, he gained national recognition when 13 of his paintings were selected by Museum of Modern Art curator Dorothy Miller for inclusion in the exhibition “Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States”. After the exhibition opened, he was courted by a number of prominent New York dealers and finally settled on Durlacher Brothers in late 1944, where his first NY gallery exhibition opened in 1945. His career as a painter was well underway.

The Young Painter (1939-1954)

The period of 1939 through 1954 represents Bloom at his oil painting peak. From the bride pictures, the treasure pictures, the chandeliers, to the cadaver and autopsy series, Bloom produced a very powerful body of work.

During this time, he filled a large number of sketchbook with ideas that would sometimes lead to the paintings we know today. The Bloom Estate holds 127 of Hyman’s sketchbooks totaling over 5,000 separate sketchbook pages.

The sketches are done in a variety of materials, including black ink, graphite, charcoal, gouache and occasionally watercolor. Gallery 3 shows a selection of sketchbook pages from the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s.

Gallery 3

Sketchbook Images (1939-1954)

Notably, in the late 1940s, as part of the “treasure picture” painting series, Bloom completed two “fully finished” gouache pictures as part of this same series. These two works are his only documented major gouache works with a full-color palette. “Old Glass” was purchased by New York dealer/collector Edith Halpert for her personal collection while “Pompeian Glass” was purchased by Karl Zerbe, the head of the Department of Painting, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Gallery 4

Gouache "Treasure pictures" (1948/'49)

In 1952 Bloom began to experiment with producing large-scale, fully rendered drawings as cartoons to be used for paintings; this approach lasted a few years and was primarily concerned with anatomical themes. He abandoned the practice after deciding that this approach interfered with his painting process when it came to rendering the works in oil.

In his 1958 article Chaet wrote:

The oversize Conté drawings exhibited a few seasons back in his retrospective at the Whitney Museum were intended, we learned, as actual "cartoons" for paintings. He found that transferring these "cartoons" to canvas was a very difficult job at best. And when it was possible to transfer them properly he found it uninspiring to paint on an already completed vision; there was little margin for development. He jokingly remarked that "cartoons would be practical if an apprentice would do the transferring and the painting."

Bernard Chaet, 1958

In gallery 5 we can see side-by-side comparisons of the two drawings that ultimately had counterparts in oil, while gallery 6 shows large conte crayon drawings never resulting in oil renditions.

RIGHT The Anatomist (1953), Oil On Canvas, 70.5 x 40.5 in.

Both in the collection of The Whitney Museum of American Art

RIGHT Cadaver on a Table (1953), Stand Oil And Dammar varnish, 52 x 40 in., Currier Museum of Art.

Gallery 5

conte crayon with related oils (1952)

Gallery 6

conte crayon without oil counterparts (1952)

In addition to the anatomical pictures, Seance/Medium subject matter was incorporated into Bloom’s visual vocabulary starting around 1952. Two of his early seance paintings, “The Medium” and “Apparition of Danger”, were purchased by Joseph Hirshhorn and are now in the collection of The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. In gallery 7, seance theme works from this period are shown, in ink, charcoal and conte crayon.

Gallery 7

mediums/seance (1953 - '54)

Bloom’s renewed engagement with drawing in the early 1950s — initially undertaken as an aid to painting — became very significant; by 1955 more and more of his attention would become devoted to drawing for its own sake. He seems to have reignited the passion for drawing he had as a teenager and was eager to immerse himself in applying his considerable skill with works on paper to entirely new subject matter using an expanded set of materials. As was his practice in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, he returned to approaching drawings as fully realized works. A new chapter was unfolding.

The Mature Draughtsman -- PART I (1955-1961)

1954 was a very notable year for Bloom: in March his Durlacher Bros. gallery show opened, followed by the opening of his major museum retrospective in April. His painting “Apparition of Danger” was featured on the April cover of ARTnews and a full page color image of his “Slaughtered Animal” painting was featured in the April 26th issue of Time magazine. Also in April was his supervised LSD experiment with Harvard physicians Drs. Benda and Rinkle. And in September, he married Nina Bohlen.

In 1955, Bloom moved away from anatomical subject matter as his dominant theme. He continued to explore seance scenes and rabbi portraits, plus newly introduced themes of skeletal fish and turban squash still lifes. His output in oils continued at his typical pace of about 5 works per year, but his output of works on paper skyrocketed.

In 1955, Hyman and Nina started going to Lubec, Maine for three weeks every August. The experience of Lubec becomes very evident in Bloom’s themes, which now include a number of fish skeleton drawings and, for the first time, landscape works inspired by the Bold Coast area of Lubec. The Bold Coast is adjacent to what is now Quoddy Head State Park, the easternmost point of land in the United States. More information about Hyman and Nina’s time in Lubec can be found in this essay.

Bloom had sporadically used fish as subject matter going as far back as the early 1940s, but these earlier works were essentially one-offs and didn’t develop into a series until 1956. He produced a large number of fish pictures in the mid to late 50s — mostly drawings, and again in the 1970s and 1980s – mostly paintings. The fish paintings of the 1970s are some of his most iconic works.

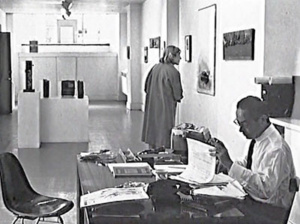

While Durlacher Brothers in NY was Bloom’s primary representation for paintings, the Swetzoff Gallery in Boston provided primary representation for his works on a paper. Hyman Swetzoff worked very closely with Kirk Askew, the owner of Durlacher Bros., and he did sell paintings on a fairly regular basis, acting as an agent for Askew. Conversely, Askew would get occasionally take drawings on consignment from Swetzoff for sale at Durlacher Bros. But there was a clear understanding: Askew provided primary representation for oils and Swetzoff provided primary representation for works on paper.

Swetzoff had met Bloom in the mid-1940s and they remained good friends. Swetzoff established a healthy market for Bloom’s early student works and contemporary studies, which were both plentiful. The vast majority of Bloom drawings produced in the 1950s and 1960s were sold by Swetzoff.

The Swetzoff Gallery held solo exhibitions of Bloom drawings in 1957 and 1965. These gallery exhibitions served as precursors to the museum shows taking place in 1957 and 1968, and Swetzoff was heavily involved in both museum exhibitions.

Through Hyman Swetzoff, Bloom met Jerry Goldberg, a businessman who, like Bloom, had grown up in the West End. Goldberg became a good friend and patron, and paid Bloom a monthly stipend in exchange for drawings. Eventually, through acquisitions directly from Bloom as well as purchases from Swetzoff Gallery, the Goldberg Collection of Bloom drawings grew to over 35 works. Of the 17 drawings included in the 1960 “Francis Bacon/Hyman Bloom” exhibition, 13 came from the Goldberg Collection. Many of these drawings, thanks to the generosity of Goldberg’s son and daughter, are now in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and The Morgan Museum and Library in New York.

Another notable collector who collected Bloom works on paper was Boston dentist Dr. Earl stone. In the late 1950s and through the 1960s, Dr. Stone built a collection of 8 excellent large Bloom drawings. All are now in the hands of private collectors.

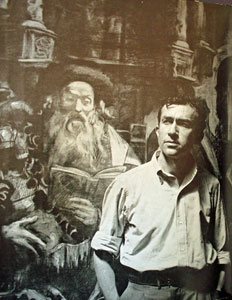

Rabbi pictures merit special attention within Bloom’s body of work. His relationship to Judaism is often brought up in discussion of his heavy use of rabbi imagery. After all, just after his bar mitzvah in 1926, he had turned his back on practicing the faith that he was born into, and by the late 1930s was deeply immersed in the study of Eastern religions and Theosophy. Yet, from the 1940s on, he produced more rabbi portraits than any other single subject, and by a wide margin.

Bloom’s comments on rabbis as subject matter provide insight as to why he found this theme so compelling. He said “[Rabbis] represent the best that can be made of a human being…even if they don’t live up to that standard, they still have a symbolic value.” 7

Rabbi pictures merit special attention within Bloom’s body of work. His relationship to Judaism is often brought up in discussion of his heavy use of rabbi imagery. After all, just after his bar mitzvah in 1926, he had turned his back on practicing the faith that he was born into, and by the late 1930s was deeply immersed in the study of Eastern religions and Theosophy. Yet, from the 1940s on, he produced more rabbi portraits than any other single subject, and by a wide margin.

Bloom’s comments on rabbis as subject matter provide insight as to why he found this theme so compelling. He said “[Rabbis] represent the best that can be made of a human being…even if they don’t live up to that standard, they still have a symbolic value.” 7 Perhaps the most astute summary of Bloom’s use of rabbi imagery is contained in the catalog essay of his 1968 drawing exhibition, where Marvin Sadik wrote:

In his drawings of Rabbis, Bloom has striven to personify his Ideal Man. Garbed in and surrounded by all the regalia of religious ritual, these Rabbis are not only involved in the world of Hebrew orthodoxy, but, seemingly saturated with immense learning and profound wisdom, they have risen above it, and are, ultimately, mystics. And it is this mysticism which interests Bloom most, an ecstatic state, which, though it has been arrived at here through the medium of a specific religious tradition, in the final analysis, has nothing to do with it.

Marvin Sadik, 1968

Rabbis were his chosen metaphor for what man should strive for: the dedicated pursuit of knowledge & enlightenment. It is ultimately his completely optimistic view of what man can achieve in a lifetime. It’s what he was striving to achieve as a spiritual being and artist.

It’s worth noting that while Bloom was no longer engaged in the practices of Judaism, he hadn’t completely turned his back on some of its fundamental traditions. His extensive library, in addition to numerous texts on Hinduism and Buddhism, included volumes exploring elements of Jewish mysticism such as Kabbalah. And ultimately, at life’s end, he opted for a traditional Jewish burial.

Shown in gallery 8 is the series of four large rabbi drawings completed in 1955 which are among Bloom’s best figurative works. All are now in institutional ownership.

Gallery 8

rabbis (1955)

In 1956, Bloom shifted to mostly ink and conte crayon. He completed a series of works in black ink and another series in white ink. He also produced a number of conte crayon works using both sanguine and brown conte crayon.

Notably, Bloom completed his first known landscape drawing inspired by Lubec, Maine, a black ink drawing (Gallery 9, image 1). Dated Aug 15th, this is a rare work that Bloom completed while actually staying in Lubec8.

He also completed a series of “beggar pictures” in black ink, some of which are shown in gallery 9. Bloom would reference beggars when discussing certain similarities between artists and rabbis. In her essay for the 2006 exhibition “Hyman Bloom: A Spiritual Embrace” 9, curator Katherine French wrote :

...he uses the word ‘beggar’ to describe artists and rabbis, who both must depend on society to make their living. “Rabbis were the aristocrats of learning,” he says, deeply respectful of a knowledge acquired through diligent study. “But rabbis had to live through the help of rich people. They did the service, but they had to beg for everything to be supported.” The connection between the painter and his chosen subject is clear.

Katherine French, 2006

Gallery 9

black ink (1956 )

Gallery 10 features a selection of white ink drawings. The white ink drawings introduced an element of color through the use of dark toned paper in either red, green or blue. The color from the dark toned papers has been lost in previous black & white reproductions, and unfortunately some of the images in gallery 10 are from B&W sources. These images will be updated as better photos are obtained.

Theme-wise, the beggar series continued and a new theme of fish skeletons was introduced. Bloom had been using fish as subject matter for both painting and drawing since the early 1940s, but now the decidedly more skeletal theme developed into an important series of drawings.

Gallery 10

white ink (1956/'57)

As an example of an unconventional drawing technique Bloom sometimes employed, the 1956 conte crayon “Fish Skeletons” (gallery 11, image 1) drawing is notable for the use of dissolved conte crayon applied with both a pen and a brush.

Chaet discussed the process used in this drawing in his 1958 article:

Fish, a recent red ("Watteau") Conte-crayon drawing, reveals a seemingly mixed-media work. It is perhaps better described as a mixed-instrument drawing (if there is such a category). Let us explain. The darkest tones at the top have been rubbed with a dry brush to insure a rich, smooth dark. The watery effect at the lower right is created by wetting the already applied Conte surface. The darker brush strokes at the lower left are produced the same way, but with less water. And still other light tones are produced by working into the drawing with kneaded gum eraser. Thus far the technique is not too unusual. But the pen strokes are produced with an "ink" composed of fine Conte-crayon particles and water. These pen strokes can be seen in the upper left; here they gradually blend the darks around the form. Pen marks are also employed to detail the structures within the main forms.

Bernard Chaet, 1958

Once he had re-engaged with works on paper in the early 1950s, Bloom’s drawings generally drew upon the same themes found in his oils, along with the addition of a few new subject areas such as beggars and skeletal fish. However, one slightly unusual series of drawings took him back to his days as a young student.

The subject of mythological creatures was one that Bloom regularly employed in his early student drawings of the 1920s, and it’s the one subject from his student years that he briefly returned to in the 1950s. The best example of this is the Dragon Series executed in 1956, along with the related drawing Smoke. Two of the dragon works – there are 5 known in total – were included in Bloom’s 1957 traveling museum exhibition, his first exhibition focused exclusively on works on paper.

More than any other drawings from the 1950s, the conte crayon Dragon Series shows Bloom echoing interests from his youth, when he was fully immersed in the study of Old Master works.

Bloom’s first dragon, Dragon I, is a creative reinterpretation of one of the dragons depicted in Agostino Carracci’s (1557-1602) Two Dragons, with Details of Their Heads, and Half-Length Studies of Four Further Dragons. The Carracci drawing itself is based upon the dragon in the drawing Apollo and the Python (1589) by Bernardo Buontalenti (c. 1531–June 1608). For his own dragon, Bloom provided the creature with a smoke filled background and drew the dragon as decidedly female. The wonderful drawing Smoke was possibly completed as a fully developed study of the backgrounds Bloom used in his dragon pictures.

The dragon series, along with Smoke, might be seen as works where Bloom was simply taking pleasure in the pure joy of drawing while also providing a slightly nostalgic tangent to the type of subject he loved to draw in his early teen years. He was able to further showcase his mature, virtuoso draftsmanship while revisiting a touch of Old Master subject matter. Unlike typical 16th century depictions, Bloom’s dragon is not an demonic creature about to be dispatched by a heroic saint, but is shown alone, apparently responding to some unidentified threat; perhaps a metaphor of our untamable natural world that might be somewhat related to his large charcoal landscape drawings that would come just a few years later.

Gallery 11

conte crayon (1956)

As we saw in Gallery 4, the two early 1940s “treasure” gouaches were full of color. Now, the gouaches were strictly monochromatic, from deep blacks to pure whites. Subject matter varied, but included two excellent “Rabbi with Torah” portraits. These are two of the best rabbi portraits — in oil or on paper — that Bloom completed after the 1955 Rabbi series. One entered the Goldberg Collection while Edith Halpert purchased the other for her own collection.

Gallery 12

gouache (1956/'57 )

I spent yesterday in Hartford where I went to see the exhibition of your drawings. It is a very fine show, full of wonderful drawings and very well shown. I do wish we could have had the show here before it started on the road. Some of the drawings I know, but it seems to me the best ones I did not know. The great revelation was the landscape drawings and the drawings of the last two years which are really superb. They keep reminding me of the late 15th and early 16th century in Germany and Switzerland. The landscapes are such a completely new departure and new vision for you that I was tremendously fascinated by them. I am wondering if anything like that will appear in the new paintings. However, I am very conscious that it will be some time before I see them, and you well know that I can and do wait.

Kirk Askew, March 3, 1958

Bloom never did send more paintings to Durlacher Bros. and would put aside his oil paints entirely in 1962. Askew, not able to find a suitable buyer for Durlacher Bros. when he retired, shuttered the gallery in 1967. By the time Bloom started painting again in 1971, he had new representation in New York with the Terry Dintenfass Gallery11.

From 1958 through 1961, Bloom didn’t exhibit any particular preference in materials or subject matter when it came to works on paper. He produced major drawings in ink, gouache and conte crayon. Gallery 13 shows a selection of these works.

Gallery 13

misc. works (1958-1961)

Gallery 14 shows works that Bloom produced between the mid 1950s and the mid 1960s that are best categorized as “studies”. The subjects are those that Bloom often used for studies: head portraits, fish, and rabbi with torah. Most often done in black ink, but occasionally in conte crayon, these studies were clearly something he enjoyed producing. The head studies are sometimes in the manner of Old Master caricature portraits and da Vinci’s “grotesques”12.

Gallery 14

Ink studies: heads, fish & rabbis (1955-1965)

The Mature Draughtsman -- PART II (1962 -1971)

With the intention of focusing exclusively on drawing for 6 months, Bloom put aside oil paints completely in 1962. He said “I thought by reducing the variables I could get to fundamental issues. The Sung painters, after all, have a complete aesthetic in black and white, and I had hoped by imposing such limits I might be able to give greater strength to the whole composition. Also I wanted to explore charcoal tone as Redon had done, and pursue ideas I had developed from studying the drawings and prints of Altdorfer and Bresdin.”13

Six months would turn into almost 10 years.

Between 1962 and 1967 Bloom completed a series of large (up to 6 ft. x 9 ft.) landscape charcoals14. In a somewhat uncharacteristic move for Bloom, the works in this series were numbered, dated and initialed. Of the twenty one completed works in this landscape series, nineteen are currently located.

From 1962 through 1964, Bloom completed the first fifteen of the numbered landscapes. Then, in 1965 and 1966, he mostly shifted his attention to a series of large Astral Plane charcoals, completing seven in all. Returning to the numbered landscapes in 1967, he finished out the series with works #20 through #24.

The 1965 Swetzoff Gallery show consisted of twelve of these large charcoals. The 1968 travelling museum exhibition included twenty four of the large charcoals (including both Landscape and Astral Plane subjects) as well as twenty earlier works, and was well received:

From the San Francisco Chronicle:

It is not to be missed. I was particularly swept away by the landscapes which remind one of Altdorfer, Bosch, Bresdin, Blake and all other Gothic and romantic masters of dense detail and mystical inspiration, But after a visit to the San Francisco Museum… [they] will remind one forever of Hyman Bloom.

Alfred Frankenstein, San Francisco Chronicle, July 10, 1968

From the Boston Globe:

Bloom is not only a master craftsman and draughtsman, he also has something to say... Many of his drawings are limited in theme to the forest primeaval, as it were. Charcoal (or conte crayon) is the only medium used. Color is nil. Only black and white and a thousand and one shades of grey are asked to tell the story here. A native of Latvia, who came to this country in 1920, Bloom handles charcoal like an old master. In his drawing, light and shadow, shapes of all description fluid compositions, space and basic structure are all so beautifully related one to another and to the overall theme that there isn't a jarring note throughout. We urge you to see it. It's a knockout.

Edgar Driscoll, Boston Globe Nov 24, 1968

Gallery 15

Large Charcoals (1962-1969)

The high note of the museum show’s April opening was soon cut short by the tragedy of Hyman Swetzoff’s murder the following month. Having lost both Durlacher Brothers and Swetzoff Gallery representation within a 12 month span, Bloom’s representation — through a recommendation from Kirk Askew — was taken over by the Terry Dintenfass Gallery in NY. for both paintings and works on paper. It would be four years before Dintenfass presented a gallery exhibition; she knew, no doubt from conversions with Kirk Askew, that it was best not to push Bloom for new work.

The 1968 exhibition would be the last museum exhibition dedicated to Bloom’s works on paper. Subsequent museum shows have included a selection of drawings, but a dedicated works on paper exhibition is long overdue.

The Later Years (1972-2009)

Gallery 16

Monotypes, etchings, watercolor (1970-1985)

Gallery 17

Late year sketches (1980-2006)

Summary

Hyman Bloom’s lifelong engagement with works on paper produced a rich body of work unique in 20th century American art. Bloom was an incredibly gifted young draughtsman who was fortunate to meet Harold Zimmerman, whose influence helped Bloom further develop compositional skill. His drawing output as a teenager still stands as an admirable body of work. Bloom’s passion for drawing and his discipline in furthering his skill set with a variety of mediums, resulted in a large number of major works on paper, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s.

During the 2019/2020 Bloom exhibition at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Holland Cotter, co-chief art critic of the New York Times, was one of several presenters during an afternoon Bloom symposium at the museum. Cotter’s presentation concluded with the following remarks:

People tried to label his work: Expressionism, Abstract Expressionism, Symbolism, Jewish art, Spiritual art. But nothing really worked, no label was accurate. No label was enough ... Despite the fact he came on the scene and had his biggest public successes in the 1940s and 50s, I don’t really in my mind associate his art with that time. I think of it as countercultural in the 60s sense. A resistance to an established order, certainly to the “anti-spiritual in art” order that has that gained dominance from the 1960s onward in academic circles. And I think of it as multicultural in the present sense; an art that synthesizes global influences to create something brand new, not seen before ... ...no art, past or present looks like Hyman Bloom's. He's a solitary wonder. His apartness continues to be a liability to his placement in art history, but it is a great, great blessing for us all.

Holland Cotter, Boston MFA presentation, February 9, 2020

A long look at Bloom’s drawings underscores the accuracy of Cotter’s remarks. Bloom’s deep interest in Eastern — as well as Western — art and philosophy, his reverence for past masters, along with his technical virtuosity, led to a body of work that is like no other and merits continued study.

While there are only a handful of missing Bloom paintings, there are dozens of missing major drawings. We will be fortunate if some of these drawings are located and published in the coming years.

End Notes

- Chaet, Bernard. “Drawing Techniques: Interview with Hyman Bloom.” Arts, March 1958, 66-67.

- Bookbinder, Judith A. “Figurative Expressionism in Boston and Its Germanic Cultural Affinities: An Alternative Modernist Discourse on Art and Identity.” PhD diss., Boston University, 1998 (UMI Number: 9823222).

- Rosamond was married to the artist Carl E. Pickhardt Jr. who had also studied with Zimmerman. Her father, Edward Waldo Forbes, was the director of the Fogg Museum of Art at Harvard University and a Boston MFA trustee.

- The footage is not publicly available, but a portion of Nina’s explanation was included in the final edit of the film.

- Eight Drawings by Hyman Bloom With a Note by Hyman Swetzoff. The Massachusetts Review, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Spring, 1962), pp. 543-554\

- Letter from Halpert to Swetzoff dated August 23, 1961, Swetzoff Gallery Records, 1941-1968,Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

- French, Katherine. Hyman Bloom: A Spiritual Embrace. Exh. cat. Framingham, MA: Danforth Museum of Art, 2006.

- Bloom and Bohlen would spend 3 weeks every August in Lubec, when Bohlen’s parents would travel and the Lubec house was available. Bloom would spend days at a time in the deep woods of the Bold Coast area with both large and small format cameras. He would later view transparencies in his studio before undertaking works using the Zimmerman method of drawing from memory and imagination.

- Thompson, Dorothy Abbott. Hyman Bloom: The Spirits of Hyman Bloom: The Sources of His Imagery. Exh. cat. New York: Chameleon Books, in association with the Fuller Museum of Art, 1996.

- Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Kirk Askew Papers, 1928-196

- Terry Dintenfass recounts her initial meetings with Bloom in “Interview with Terry Dintenfass, Conducted by Paul Cummings”, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Read the online transcript.

- The Swetzoff Gallery sales ledgers show a good number of these studies were sold. As with Bloom’s student drawings, these studies provided a price point that was quite a bit lower than Bloom’s larger, fully rendered drawings

- Thompson, Dorothy Abbott. Hyman Bloom: The Spirits of Hyman Bloom: The Sources of His Imagery. Exh. cat. New York: Chameleon Books, in association with the Fuller Museum of Art, 1996

- The numbered and dated Landscape charcoals, along with 7 Astral Plane pictures:

- 1962: 1, 2, 3, 5

- 1963: 4, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14

- 6 & 7 were never completed

- 1964: 16, 18, 19 (two versions)

- 15 & 17 were never completed

- 16 & 18 are currently unlocated

- 1965: 3 Astral Planes

- Self Portrait with Spider

- On The Astral Plane: In A Cave

- On The Astral Plane: On The Dung Heap

- 1966: Landscape #22 and 4 Astral Planes

- On The Astral Plane: Beelzebub

- On The Astral Plane: Beelzebub, Half Length

- On The Astral Plane: Cold Anger

- On The Astral Plane: Up To Their Necks

- 1967: 20, 21, 23, 24

- NOTE: in 1979, on request from collector Phillip Isaacson, Bloom completed one additional large charcoal landscape. It was not numbered as part of the original series.

- Hyman Bloom Paintings and Drawings, Terry Dintenfass Gallery, New York, 28 March-22 April,1972.

- The Pan Orient Arts Foundation was co-founded by Bloom and James Rubin in 1960 and was devoted to the collecting, recording, and study of South Indian classical music. The Steak and Chop House stationary came into use as sketch paper sometime after 1972, the year Bloom moved to Inman Square in Cambridge. The Steak and Chop House was a business run by relatives of the Berkowitz family just prior to the opening of the original Legal Sea Foods in 1968 by George Berkowitz. Per Roger Berkowitz, excess supplies of the Steak and Chop House business were stored above Legal Sea Foods in the same space that George Berkowitz invited Bloom to use as a secondary studio. Bloom put the obsolete business stationary to good use.

Selected Bibliography for Works on Paper

Online (click on the publication image or author name to read the essay)

Sigmund Abeles,

The Drawings of Hyman Bloom: An Artist's Appreciation, Color & Ecstasy: The Art of Hyman Bloom, The National Academy of Design, 2002

Bernice Davidson

Drawings by Hyman Bloom - Introduction, 1957

Marvin Sadik

The Drawings of Hyman Bloom,The William Benton Museum of Art, School of Fine Arts, University of Connecticut, Storrs, 1968

Hyman Swetzoff

Eight Drawings by Hyman Bloom, with a note by Hyman Swetzoff, The Massachusetts Review, Vol. 3, No. 3 (Spring, 1962), pp. 543-554.

Offline

- Chaet, Bernard. “Drawing Techniques: Interview with Hyman Bloom.” Arts, March 1958, 66-67.

- Carl E. and Rosamond Forbes Pickhardt Papers concerning Harold K. Zimmerman, ca.1932-1943, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

- Swetzoff Gallery Records, 1941-1968, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

- Harold K. Zimmerman Papers, 1930-1954, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC