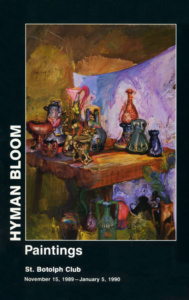

Hyman Bloom Paintings

by Dorothy Abbott Thompson

© The Estate of Dorothy Abbott Thompson

Thanks to the Estate for permission to reproduce this text.

Hyman Bloom has been variously described as a baroque painter, as a painter of the grotesque, an expressionist, a Jewish painter, a realist, and perhaps most surprisingly of all, by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning as the first of the abstract expressionists. His work, in fact, eludes classification. He would agree, believing as he does, that all attempts at categorizing art are inimical to the creative process. Bloom is an eccentric, a poet in paint, a visionary whose life and work are inextricably woven. It has been his task as an artist to distill his life experiences, to absorb and transform them. He has sought to paint the shape of emotions, dreams and fears, and the memory of ecstatic states. His mastery of draughtsmanship and the use of materials combine with the intuitional image in his drawing to liberate in the picture that which is not directly revealed by nature.

Hyman Bloom has been variously described as a baroque painter, as a painter of the grotesque, an expressionist, a Jewish painter, a realist, and perhaps most surprisingly of all, by Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning as the first of the abstract expressionists. His work, in fact, eludes classification. He would agree, believing as he does, that all attempts at categorizing art are inimical to the creative process. Bloom is an eccentric, a poet in paint, a visionary whose life and work are inextricably woven. It has been his task as an artist to distill his life experiences, to absorb and transform them. He has sought to paint the shape of emotions, dreams and fears, and the memory of ecstatic states. His mastery of draughtsmanship and the use of materials combine with the intuitional image in his drawing to liberate in the picture that which is not directly revealed by nature.

Bloom was born in 1913 in Brunoviski, Latvia, the youngest son of Joseph and Anna Melamed. The time and the place are crucial. Many of the themes which have preoccupied him throughout his creative life are embedded in the experiences of his first seven years as a Jewish child at an historic crossroads of violence, civil war and revolution. The chronic social disorder which had been a condition of life in Eastern Europe for centuries was intensified by the First World War and the Civil War in Russia. Waves of armies, mobs and looters flowed back and forth across the countryside, Russians more feared than Germans, Cossacks most feared of all. For the Jews, always at the mercy of the powerful, violence was a fact of life. By the time he was four years old Bloom had seen the Devil in the night, his face crimson and lit from below, staring fiercely through the bedroom window, gritting his teeth in rage.

In 1920 enough order had been restored to the world for the Bloom family to revive its plan to join Hyman’s two older brothers in America; they had gone there in 1912 and changed the family name from Melamed to Bloom. Bloom’s mother was certain that opportunity was greater in the New World, where Jews, free from oppression could mingle freely and have the opportunity for education denied them in the Old World. The recent past only confirmed that Eastern Europe was a place from which to escape. To be sure America held promise, but the essential nature of the migration of 2,000,000 people, of which the Bloom family was a part, was to flee a world made intolerable by hopeless poverty and their helpless position.

With their departure from Europe the Blooms began to experience the serious dislocations of life so common among the thousands who had preceded them. What had been a traditional and rather rigid family structure, with authority vested in the father, the wife formally submissive, and the children obedient, began to collapse. Bloom’s father went to work for his sons in the leather business, which in itself represented a demoralizing loss of authority. Neither of the parents, exhausted by relentless work, had the reserves of energy needed to learn English. Frictions which already existed between the parents were exacerbated by their separate griefs and losses and the isolation forced upon them by their inability to become assimilated. Eight people were uncomfortably crowded into three rooms in the slums of Boston’s West End, and family conversations when they occurred, were filled with arguments and recriminations. Bloom’s mother was frequently ill, and Hyman as the youngest child was sent periodically to live with an aunt and uncle. Theirs, too, was a crowded, chaotic household, marked by an atmosphere of emotional violence, recrimination and a profound sense of grief and displacement. Bloom began to see the intimacy of family life as dangerous and to sense that safety lay in avoiding emotional entanglements. The anxieties he had brought from Brunoviski grew, and he began to rely increasingly on his inner self, turning to a world of fantasies and imagination to which he alone had access and which he alone could control.

In the local public school Bloom was rapidly learning English though at home the family continued to speak Yiddish. Inevitably he came to feel that he was subject to the tensions of moving daily between two worlds: at home the world of Eastern Europe, emotional, capricious and anxiety filled; at school, America, open and challenging. His parents, unable and unwilling to abandon ancestral beliefs, and clinging to old ways and customs, reassuring in their familiarity, remained outsiders even in the absence of anti-Jewish barriers. But for Hyman the image of a wider society glimpsed in public school provided evidence, however fragmentary, that in America a Jew could be a full member of society, not consigned to live forever at the mercy of others. The feeling that he was straddling two worlds increased his sense of existence as tension, issue and drama. Life was woven of contradiction and paradox, with the price of self-realization being alienation and loss. It was not, as he has said, “a very comfortable nor easy way to live.”

When Bloom was 14 his eighth grade art teacher, Mary Cullen, suggested that he enroll in the drawing classes being offered at the West End Community Center. It was there that he met the teacher who was to be the most important influence of his creative life. Harold K. Zimmerman was an art teacher still in art school himself, scarcely 10 years older than his pupils. He went from settlement house to settlement house teaching a method of drawing which relied upon the imagination and emphasized “picture making,” the development of an organic unit defined by balance and harmony. He taught his pupils that it was the composition, the movement within the enclosure of the drawing, the rhythms of the various elements that mattered, not the illusion of movement in outward life.

It was a manner of working that perfectly suited Bloom’s nature. It gave primacy to the intuition, allowing the inner self to guide the pencil and the hand. The artist became the medium through which the dream became form. From Zimmerman’s teaching Bloom extracted the things which characterize all his mature work: mastery and control and an ability to give form to the emergent sensibility of the artist himself. As he describes the process:

“The ideas are waiting and when one is ready they come to the fore. Paintings are made at a creative level behind the scenes; the curtain is drawn back and then the interaction takes place, from the inner self to the hand, and then to the brush and pen. The message of the painting is to be found in the hidden side, the something apprehended under the surface of life. You must see into things to see their reality, things are not to be imitated but to be revealed.”

During their high school years Bloom and his equally talented friend, Jack Levine, continued to study with Harold Zimmerman, and in 1930 they were brought to the attention of Professor Denman Ross of Harvard University. Professor Ross, impressed with the two young virtuosi, accepted them as proteges, saying:

“These boys have already reached discrimination, appreciation, and judgement. . . . they are able at the ages of 15 and 17 respectively to produce imaginative designs of unquestionable merit. In other words they are able to think in terms of drawing and painting and able to express themselves as easily as they do in talking and writing. Ross introduced them to the Old Masters and taught them painting according to the complex Denman Ross color theory. Most importantly he became their patron, providing a monthly stipend and arranging for Zimmerman to have studio space where he could continue teaching.”

By 1934 the Federal Artists Project of the WPA replaced Ross as patron, and it was in his years on the project that Bloom created his first mature work. Dorothy Miller, wife of Holger Cahill, the Director of the Artist’s Project, selected twelve of Bloom’s paintings for inclusion in an exhibition “Americans 1942” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It was Bloom’s first opportunity to exhibit his work. The Museum bought three of his paintings, and his work attracted the attention of many important people in the art world, such as James Johnson Sweeney and Alfred Barr. In the fall of 1945 the Stuart Gallery in Boston presented a major exhibition of Bloom’s work. It created a stir in Boston and was received with a mixture of enthusiasm and ambivalence by critics and public alike. In 1946 Kirk Askew of Durlacher Brothers Gallery became his dealer. Askew was strongly supportive of Bloom’s work, and the artist’s career developed rapidly. In 1950 paintings by Bloom were included in the Venice Biennale. By 1954 he was the subject of a large retrospective which originated at the ICA in Boston, traveled across the country and concluded at the Whitney Museum in New York. Art News for April of that year reproduced his painting “Apparition of Danger” on the cover, and he was the subject of a lengthy article in Perspectives USA by the distinguished scholar Sydney Freedberg. In the short twelve years since his first painting had been exhibited, he had become acknowledged as an American master.

Throughout his career as an artist Bloom has had a consistent thematic commitment. From his earliest student work in the Fogg Museum to the present, his work has dealt with the impermanence of things — the transitoriness of life; with human dignity and sorrow. The innermost core of his work is in his Jewish origins. It is the point of departure for examining ambiguity, mortality, the overwhelming of the weak by the strong. The emotional intensity of the Eastern synagogue, the rhapsodic quality of cantoral singing and the richness of the Yiddish language appear in his paintings in the use of glowing color and jewel-like paint surfaces.

Bloom is committed to a cosmic consciousness, a belief in predestination and the concept of time as illusion. His beliefs reflect values more consistently found in earlier or non-Western cultures than in our own rationalist society. His life-long interest in the occult illuminates the subject of metamorphosis and the nature of reality in which the boundaries of perception are shifting and unclear, subjects continually explored in his paintings throughout his career.

Hyman Bloom has said that it is through art that everything has opened up to him. With teachers and friends whom he has met as if by appointment, and the workings of fate which brought the right people together at the right time, he has been able to achieve the personal transformation and freedom to create with art his own spiritual world.

Since Bloom’s character from his earliest years has been shaped by forces that have led to alienation, a sense of loss, and anxiety, creating art became for him a requirement for survival, an assertion of purposiveness over the forces of negation. He believes his image-making to be less a matter of choice than of personal necessity. Aware that life is a consciously fearful condition, filled with tension and paradox, Bloom has found the greatest hope of resolution in the creation of art.

— Dorothy Abbott Thompson