Hyman Bloom

by Frederick S. Wight

Originally published by The Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA. April, 1954

- Catalogue Essay

- Announcement in the ICA Bulletin

Hyman Bloom is one of the strongest painters in America today. He is essentially a religious painter. His work stays with a few deep and persistent themes; the separate paintings are related as the Psalms are related. The spectator is given a scene, but what Bloom has chosen for subject is not visible. It is progressively his self-awareness, his Jewish identity; it is childhood, birth, the mystery of origins: and in a more recent series of canvases, it is mortality. In short he has painted a testament, at times recognizably an Old Testament.

Hyman Bloom is one of the strongest painters in America today. He is essentially a religious painter. His work stays with a few deep and persistent themes; the separate paintings are related as the Psalms are related. The spectator is given a scene, but what Bloom has chosen for subject is not visible. It is progressively his self-awareness, his Jewish identity; it is childhood, birth, the mystery of origins: and in a more recent series of canvases, it is mortality. In short he has painted a testament, at times recognizably an Old Testament.

It is a curious thing that such a testament should re-emerge in New England with an intensity almost forgotten. This is more than accident of migration, as Bloom is well aware. He has been conscious of the Puritan tradition — the early sense of retribution and the relenting atmosphere of Transcendentalism — and has seen its correspondence to his own orthodox upbringing and his later interest in philosophy.

Bloom’s early background is Baltic. His painting is Eastern European in its expressionist splendor, with an oriental instinct for coruscations, for jewel-like effects. Bloom has escaped the decorative diffuseness of Russian painting, just as he has escaped the orgiastic vanity of Expressionism — so pleased with the ecstatic moment. The emotion in Bloom’s work is deep and meditative, the feeling moral rather than sensuous.

Migration, with its problems and tensions, is one of the great commonplaces of our century. To make the best of it, to add two lives and not subtract one from the other, is a major problem for an artist. Such a salvaging of everything past and present is essential to Bloom. He has dealt with a whole experience, and made it a total human account, taking the accident out of experience.

Hyman Bloom first saw the light of day in the village of Brunoviski, a mere crossroads in Lithuania, a few clustered farms and some fifty or sixty people. The place was variously close to the Latvian border — in the days that Bloom recalls the frontiers changed daily. Bloom’s father, like the father of his later friend Jack Levine, was a shoemaker, a trade of some importance in the village. He made shoes — he did not repair them with a machine.

Bloom was born in 1913. In that year two much older brothers moved to America. The remaining members of the family were due to follow. As it was, they were trapped by the First World War and were unable to leave before 1920. By that time they were only too glad to get away. The war that Bloom witnessed was a war for temporary independence, Latvians fighting Russians with the help of German mercenaries who lived off the peasantry as they went along. Bloom spent his first seven years in Latvia and was old enough to remember.

He was the youngest of four. The two brothers in America, nearly a generation older, were only a legend to him, but there was a third brother closer to Hyman’s age. The family name was Melamed. It became Bloom with the move to America, as though to make the change complete. The Melameds spoke Latvian, German, Russian and, of course, Yiddish. Bloom has forgotten the German, Russian and Latvian. His mother’s father was a teacher, and his mother fostered the idea that her side of the family had an intellectual background, but Bloom thinks that mothers claim this the world over.

When they moved, Bloom discovered the outer world, first nearby Bausk on the Baltic, then Riga. They sailed from Riga to Copenhagen, were delayed here a month, and then came directly to Boston, to Auburn Street in the West End. Here they joined the elder brothers who were established in a leather goods business, manufacturing bags and briefcases. Bloom’s father worked for these two sons for the rest of his days.

The boy went to Washington High School in the North End. An art teacher, a Miss Cullen, got him “started” when he was thirteen or fourteen. She advised him to go to the West End Community Center in North Russell Street, and here he met Harold Zimmermann. This man was to have a determining influence on Bloom’s development. He had been teaching a year at the Roxbury Center and one of his pupils was Jack Levine. He showed Jack’s drawings to Hyman, who remembers looking at them with awe and envy and asking if he could hope to do as well. Jack was two years younger than Bloom. From now on, the two boys had parallel experiences that only served to point up the divergencies in their temperaments. Both worked along with Zimmermann, and both came under the influence of Denman Ross of the Department of Fine Arts at Harvard, who strove to foster their talents.

Zimmermann was a painter in difficult circumstances. Denman Ross was a collector, benefactor of the Fogg Art Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, and a painter in his own right. Both Zimmermann and Ross made an extraordinary effort to help Bloom and Levine. Zimmermann had his teaching to offer. Ross not only taught, but he made work space available at the Fogg Museum and later hired studios for Zimmermann and the boy painters on Brattle Street in Cambridge and on Dartmouth Street in Boston. He gave both boys a stipend of twelve dollars a week.

Bloom and Levine viewed these men somewhat differently. The two views should not be allowed to refute or cancel each other. Their divergencies are no doubt largely subjective. As time went on, Levine became irked by Zimmermann, aware that the teacher had for some reason grown to reject his work, and he venerated Ross. This veneration survived the fact that Ross had Procrustean ideas about the art of teaching. Believing that the method was all, he was prepared to give very little credit or play to the personality much less the originality of a pupil. But for Levine this was overbalanced by the dazzling gift of the past: it was Ross who led him into the world of the museum and opened his eyes to the great inheritance. Levine has respect for intelligence, for awareness, and he felt that Ross banished his ignorance.

Bloom on the other hand felt that his primary debt was to Zimmermann, whom he still sees as his spiritual father. It was Zimmermann who showed him “the possibilities of the imagination”. And from both accounts, one thing stands out. Both boy painters were athirst for the experience of art. They had come from outside the orbit of Western Europe, and the European tradition was not something ripe for rejection, but a precious discovery, a great revelation. For them, the past was new too.

For Bloom, Zimmermann was an inspiring teacher who made it possible, he still feels, for him to become a painter. Zimmermann expected his pupils to work from memory or from the imagination. Drawing was making or building. To give an idea of Zimmermann’s method, Bloom cites Florence Cane’s “method of relaxation”. To this utilization, or stimulation, of a child’s vision, Zimmermann “applied standards of mature performance”. “He disinhibited the student so that he could follow a succession of images. It was a technique of working which made it possible to follow the movements of the imagination.” Later, in his own teaching, Bloom adopted Zimmermann’s approach.

One thing that Bloom has preserved from Zimmermann is the pragmatic belief in “learning only what is specifically necessary to deal with a particular problem”. If you want to draw or paint hair, for instance, you look into the matter, see how it has been done before and figure out how you want to do it. Zimmermann took time out to show Bloom how Botticelli drew hair. “He wanted to make available all that might be useful. He gave you a chance to view everything, opened up a whole library of experience. He didn’t come between you and a great painter or inflict a point of view.”

Seeking for the needed thing in place of a general or formal discipline is not unrelated to Bloom’s larger educational pattern. Bloom did not go to college and in consequence he is a reader. His education is from the public library. “I never had any difficulty in getting information either from books or through inquiry from the right person.” This pursuit of learning under the stimulus of immediate purpose took on spiritual as well as practical qualities in Zimmermann’s thought. He also urged Bloom to go after what he admired and make it his own. Bloom admired Michelangelo, Tintoretto, and Tiepolo. Above all, “Blake was my hero from way back” — a fact which shows clearly enough in the early drawings.

It should be stressed that the two future painters only drew during the formative years from fourteen to nineteen. They underwent an enormous discipline, not in copying but in imagining and understanding. When Bloom was about nineteen, he began to paint with Denman Ross, “but it didn’t amount to anything that year because it was from models.”

Bloom and Levine and Zimmermann too — who was only ten years older than Bloom — were being swept into the orbit of Denman Ross’ interest. Ross was able and willing to change the pattern of their lives. There is an element of rashness in influencing genius. Were his protégés to go to Harvard, Ross meditated? He finally decided, according to Bloom, that college was inappropriate. “Although whether Harvard was inappropriate for us or we were inappropriate for Harvard, I never knew.”

A trip with Zimmermann to the newly opened Museum of Modern Art in New York brought Bloom in contact with the canvases of Rouault, and he saw a Soutine. He was impressed — “it was a clarifying experience, and I began to imitate Rouault to Zimmermann’s chagrin and Ross’ dismay. Ross couldn’t stand Rouault or even Cezanne”.

Early recognition in effect amounted to a second transplanting when the first great transplanting to a new country was still in process. Bloom went home to elderly parents who had brought with them their orthodox outlook, as limited in fact as it was scholarly in intent. The tension between the old family tradition at home and the pull of Americanism on a new American was very real. “The problem worked out very badly. Art for me was the third way out.” Bloom is given to third ways out, rather than to taking sides. He has always wanted a reconciliation of conflicting elements. The fusion of such disparate elements is a life’s work, it implies a philosophy, and is enough to account for the depth, the richness, and the slowness of Bloom’s development.

Bloom read philosophy. Spinoza was one of his first interests. “I read him quite young: his Ethics, his Essay on the Improvement of the Human Understanding—his definition of God was the first that made any sense to me.” Bloom went on to Plato and Kant. But above all he was impressed by Ouspensky. He thought, and thinks Tertium Organum “a basic book”.

Bloom has studied astrology and has been a Rosicrucian. He understands these deviations as part of a search for substitutes for an orthodox faith. His thought and his work, as they have matured, are one and the same thing — “an attempt to cope with one’s destiny and become master of it”. He is refreshingly “in search of a greater individualization, needing less support from groups”. With this preoccupation, it would be strange if he did not have reflections on psychoanalysis — that great Jewish contribution to the thought of our time. For him, “psychoanalysis, like mysticism, is concerned with the development of a greater consciousness”.

These inner searchings parallel the Depression years, the chanciness of the 1930’s for which Bloom was both well and ill prepared. His training had been in the arts. He had been encouraged and supported. When he was twenty and Jack Levine was eighteen, the two young painters set themselves up in a studio in the South End — 21 Kirkland Street, near the Morgan Memorial. After three years Levine could afford to move out; he had a dealer; he had begun to sell.

But those were the years when the real support for the arts came from the government. “PWA — WPA — I was in all of them. I was used to getting off them and then on again. We didn’t live too well, you understand, it was a minimum level. None the less, whatever painting there is in America today is due to WPA.” Holger Cahill, head of the Federal Arts Project, came to Boston with his wife Dorothy Miller, who was in search of new work for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. Dorothy Miller came to know Bloom’s painting. As a result, Bloom was included in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition of discovery and recognition: Americans 1942.

This exhibition was early in terms of what was to come. Yet the thematic character of Bloom’s work was already clear. The themes in his work are concentric; they are all widening aspects of self-discovery. The innermost theme is his own orthodox background, by no means to be repudiated — it would be a denial of parents. This theme opens with the SYNAGOGUE. There are two versions, one belonging to Millard Meiss, the larger canvas in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art. Both were worked on simultaneously during 1940 or 1941. Here Bloom identifies himself with a group — it being still the practice of the age for a man to define himself by belonging. This is the confession of origins, the admission of roots; yet Bloom is the observer here, beyond the railing rather than a participant.

The paintings are in a low key, to reach for resplendence. Here is a vaulted, mystical world in which light itself has a controlled meaning. Here light has been for centuries a sacred symbol. Objects in Bloom’s paintings seem to be luminous rather than to reflect light, to have the qualities of precious stones; the artist knows how to evoke a child’s vision so that one feels a gesture of reaching out toward a point of bedazzlement. It is almost as though the breastplate of multicolored stones of the high priest were the artist’s palette. Figures are hieratically large and small, there is a mannered Byzantine warp of necks. The paintings fuse themselves on ceremony, and for this very reason details are hypnotically obvious to the attention.

This theme continues in the JEW WITH TORAH paintings, of which there are four all told. The earliest was painted in 1940, the year of the SYNAGOGUE. From 1945 there are two, the ELDER JEW WITH TORAH and the YOUNG JEW WITH TORAH. The final example was painted in 1947. All these Rembrandtesque portraits stress a conception of spiritual identity between man and sacred symbols. Torah and figure are curiously blended in color, in handling, the very features of the man taking on a jewel-like shimmer of green and blue as though the artist had chosen this means to make flesh morally resplendent—a matter to note, for the painter will eventually make us face such colors in flesh as the colors of putrescence.

With this orthodoxy behind him, Bloom considers origins in more general terms. The theme now becomes childhood; and Bloom will move backward from childhood and approach the mystery of birth. We have both the adult philosophic query, and the child’s query, whence do we come. There is the BABY of 1941 and the CHILD IN THE GARDEN and the CHILD, both of 1945. The shift in metaphor in these last two paintings is significant. In the CHILD IN THE GARDEN, a young Buddha stands in the center of a stylized garden which might be an oriental rug — which, of course, is a garden. He exists in a nirvana, happy in his own solipsistic importance. This is prenatal isolation, as the painting CHILD makes abundantly clear. Here Bloom uses physiological language. Here, as in the later paintings of death, one hesitates to say Bloom is painting the fact. It is truer to say he is describing our situation as nature describes it.

This leads us to paintings which can be read into this theme, once we have the obvious clue. TREASURE MAP, painted in 1945, is at first sight an abstraction; then it is seen to be an archaeologist’s map of a Mesopotamian city. Consider that this is the infancy, pre-infancy of the race of men, a dim forgotten past waiting for adult re-discovery, the city having become a tumulus. TREASURE MAP, then, is simply a less physical metaphor; we are still with our subject. ARCHAEOLOGICAL TREASURE of the same year, and BURIED TREASURE painted in 1947, only shift the metaphor. The paintings now seem to be jumbles of precious stones, all purples and greens, the colors only vaguely visceral, the forms dimly ovular.

As though to give a lighter aspect of wonder to this philosophical brooding, there are two related childhood themes; the Christmas Tree series and the Chandelier series. The child interest, the childhood salvage, in the Christmas Trees one need not argue. The Chandelier paintings are not so obviously a theme of childhood. Yet both series are curiously related as Christian and Jewish symbols, and this is quite deliberate. And in both Christmas Trees and Chandeliers, the major aspect is be-dazzlement, a hypnotic taking over of the spectator’s attention.

There are four Christmas Trees, to Bloom’s recollection: an early example is on permanent loan to the Museum of Modern Art from the PWA Project; another is in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The Chandelier paintings in particular are progressively more sumptuous and ornate. They recall the chandeliers visible in the synagogue canvases; they have a quality of splendor which associates itself with ceremony.

Equally early paintings are the two BRIDES — and here there is the same prismatic effect of broken light. Nothing could make more clear Bloom’s feeling that light and color are attributes and emanations.

It seems logical enough that Bloom, having given half his art to the mystical theme of origins, should face the theme of conclusions: of death; where do we go? This is a question which can only be asked, much less answered, in figurative language. When England was Christianized, Edwin’s councilor said to the King: “While you are sitting at supper in your hall, warm and comfortable by the fire, and snow and rain sweep down outside, a sparrow flies in one door, and passing through the hall goes out at the other. For a little time it lingers; it passes through a festival, but it flies from winter to winter. So is the life of man; for a brief space it lasts, but what comes before or what follows after it, of this we know nothing.”

Mortality is the one great fact which propriety, taste, and convention struggle to smooth over. Mortality has become dubious in our culture in proportion as immortality has become doubtful, and there is the illusion abroad that the frontiers of death are retreating, as though death were being defeated or outsmarted, in short, as though death were really an unlikely thing. This great farce only masks a moral contradiction. For if we are mortal, what becomes of all the inducements to invest in ourselves in this market which has passed its peak? Bloom now coolly takes us in hand, asking us to see ourselves for ourselves, to look at the universal Buchenwald and admit that we know what we know. He takes us to the hospital, which turns out to be the place where we die — where else? These paintings come very rightly in a series too.

The early SKELETON painted in 1942, is a quite conventional opening of the theme. But then comes THE LEG, painted in 1945. This is an extraordinary painting of an amputated limb against a surgically white background. The limb is ulcerous, ironically bejewelled, carbuncular in both senses. The excellence of the canvas does not counteract the revulsion of the subject. Rembrandt’s ANATOMY LESSON is serene and mild in comparison: here the lesson is quite a different one. We are almost prepared for the corpse canvases, the ELDERLY FEMALE CORPSE and ELDERLY MALE CORPSE, painted in 1945. These figures, life size, exposed in the impersonal indecency of an autopsy, are unmitigated accounts of physical disaster. They are leprous, obvious victims of final and pointless suffering. Yet they are elderly, they have lived a long time. For that very reason, they have come to this. The artist does not ask us to pity, since of course, we are not relations. But if we were Father Damiens, we could see that they are our parents too.

Two years later Bloom painted FEMALE CORPSE BACK VIEW. This is equally somber. The painting offers some slight mitigation, and is perhaps more moving because less ghastly, in that we are not put through a confrontation face to face with someone awfully not present. The shroud or sheeting swoops impressively around the figure, vaguely suggesting a great wing. The earth colors, the sculptural weight of the whites, the gravity of the painting are imposing. This is one of Bloom’s finest achievements.

The same year, 1947, saw the HARPIES. Less monumental, its morbid subject is obscured in the handling. It is a moment before the flock of large black birds resolves itself, then it becomes clear that the harpies are finishing the last of a human feast. But the painting, curiously, is far less macabre than the telling of it. There is a rich pattern of reds and blacks, an oriental sense of complex decoration; metamorphosis is Bloom’s basic subject.

In 1948, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts invited James Johnson Sweeney to select and arrange its Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Paintings. The public via the press adjusted itself convulsively to what it saw, and the FEMALE CORPSE BACK VIEW gave it an opportunity to recognize what it did not like. But it is the nature of dust to settle and join the dust; and when this was over, the painting was exhibited that summer in an exhibition of post-war paintings at the University of Michigan, arranged by the author. Here it was viewed with the sobriety it deserves.

This theme is by no means concluded. A visit to Bloom’s studio reveals new paintings of corpses. “This theme is charged with energy,” Bloom feels. “It is a fruitful area of one’s emotional life”. Besides, Bloom warns us not to take these new corpse paintings too literally. “You are familiar with the Tibetan idea of the benign and wrathful aspects? These are wrathful aspects.” In general, these paintings are less of the hospital, more chaotically imaginative. There has been nothing like this since the Disasters of War, but it is not war. And in no sense is it social comment.

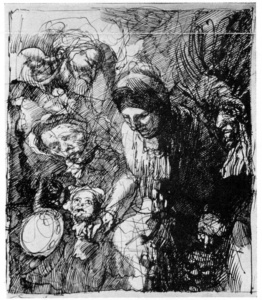

Bloom has a way of bringing a score of paintings along at once. Work on any one is spasmodic. Eventually, the canvases take on an existence of their own, and grow to maturity according to their requirements. Recently Bloom began to carry through much of the earlier development on paper, to spare repainting. Thus his new work exists also in large drawings in red or black chalk, the same size as the related canvases.

In general, the new paintings have a radically new aspect. They are no longer symmetrical compositions, with a decorative glitter, denying depth, as though everything were within reach. Instead, they are deep, tumultuous, and baroque. The light is more intense, and the color gains in proportion.

It is rare for anyone to be allowed through this door: Bloom’s studio is a conclusive and not a preliminary experience. An office building with marble stairs, on Boston’s Huntington Avenue, offers what is called professional space. On the third story, behind the frosted glass door, the scene is cluttered until it blurs, like the sight of faces in a crowd. There is also a half-room jammed with canvases — most of which will remain back-to. On every hand the large rolled drawings stand like four foot truncated columns — and most will remain rolled. The equipment for painting is submerged in the paraphernalia of Bloom’s imagination. All sorts of oddments identify themselves little by little; rocks, crystalline and weather worn, peacock feathers in an array of vases; things which are here for their iridescence. The viscera of amplifiers; music means much to Bloom. In short, it is a den, so why should there not be bones? It is a place where things become ideas, and ideas become things. “These things must be judged as paintings — you don’t expect me to found a new religion?”

Boston, June 1953

Hyman Bloom 1954: A Postscript

by Lloyd Goodrich

After a six-year abstention from exhibiting, Bloom has emerged with ten new paintings, completed from 1951 on, and a group of large drawings. All but two of these works continue the theme of mortality, but with differences. The emphasis on corruption has shifted; these are scenes of dissection, the body laid open, its innermost structure revealed. The artist shows us what we are, with a particularity beyond even Caravaggio, Rembrandt or Gericault.

The style marks a new departure. The dominant chromatic character of Bloom’s earlier work has given way, especially in the 1953 pictures, to more definite, powerful form and more conscious design. The strong sweeping movements of the forms and their complex rhythms recall the Baroque masters. Even the brushstrokes have become more dynamic, modelling with the brush. Color has burst forth into a new brilliancy, a multi-colored radiance which makes these cadavers burn like flames or flowers against the dark backgrounds.

In this new work the sense of horror is strongly present, but transcending this are deep humanity, a search for truth wherever it may lead, and the transforming power of art. The first reaction may be shock, but the final impression is one of tragic beauty.

New York, March, 1954

Exhibitions

Hyman Bloom Retrospective

The Institute’s April exhibition marks an important event in the contemporary art world: a retrospective showing of the work of Hyman Bloom. One of the strongest younger painters in America, Bloom lives and works in a top-floor, studio apartment in Boston’s Back Bay. It is now almost six years — representing a concentrated period of work —since any new Bloom canvases have been shown, let alone seen by more than a handful of privileged intimates.

The Institute’s retrospective exhibition, scheduled to travel across the country, will include 10 of the new paintings and drawings together with a large group of his older works. The dates for the Boston showing are from Thursday, April 8 to Sunday, May 16.

Bloom’s work, and indeed the pattern of his life, is composed of a duality: his consciousness of the Puritan tradition, and the pressures of his Orthodox Jewish background. On one hand, his painting is Eastern European in its expressionistic splendor and oriental instinct for coruscation and jewel-like effects; on the other, his painting reflects an emotion that is deep and meditative, and a feeling that is moral rather than sensuous.

The painter was born in a Lithuanian village in 1913, and came to Boston’s West End with his parents in 1920. An art teacher got him “started” when he was thirteen or fourteen, and sent him to study under Harold Zimmermann at the West End Community Center. Zimmermann developed “the possibilities of the imagination” in Bloom. He, and later Denman Ross of the Department of Fine Arts of Harvard, both made an extraordinary effort to help Bloom. During the depression years Bloom continued to paint thanks to the sponsorship of the government. “Whatever painting there is in America today,” he says, “is due to the WPA.”

Discovery and recognition arrived for the painter in the same year: 1942. Dorothy Miller came to Boston to search out new work for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, Americans 1942. Bloom was included. Since then he has been widely purchased for both private and museum collections and has achieved a national reputation that is steadily growing.

Essentially Bloom is a philosophic painter. His themes have dealt with the most urgent problems of man: birth, love, life and death. In essence — mortality.

To quote Lloyd Goodrich’s postscript to Frederick S. Wight’s exhibition catalogue: “All but two (of Bloom’s new works) continue the theme of mortality, but with differences. The emphasis on corruption has shifted; these are scenes of dissection, the body laid open, its innermost structure revealed. The artist shows us what we are, with a particularity beyond even Caravaggio, Rembrandt or Gericault.

“The style marks a new departure. The dominant chromatic character of Bloom’s earlier work has given way, especially in the 1953 pictures, to more definite, powerful form and more conscious design. The strong sweeping movements of the forms and their complex rhythms recall the Baroque masters. Even the brush strokes have become more dynamic, modelling with the brush. Color has burst forth into a new brilliancy, a multi-colored radiance which makes these cadavers burn like flames or flowers against the dark backgrounds.

“In this new work the sense of horror is strongly present, but transcending this are deep humanity, a search for truth wherever it may lead, and the transforming power of art. The first reaction may be shock, but the final impression is one of tragic beauty.”