HYMAN BLOOM

by Brian O'Doherty

Art in America, Vol 49, No. 3 - 1961 [This was the first in a series of Art in America "portraits" of contemporary artists] © Brian O'Doherty. Reproduced with permission.

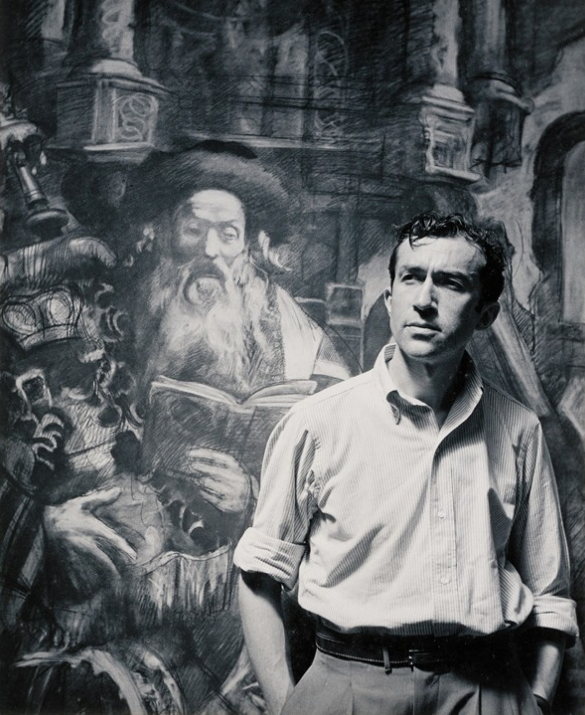

Hyman Bloom once said to me with a serious air, “There must lots of people I haven’t met.” There are lots of people who haven’t met Hyman Bloom. He pursues his craft in secretive seclusion with an almost monastic dedication.

He is something of a legend in Boston, and what Hyman Bloom is painting now is hidden behind the deceptively fragile, but iron curtain of his silence. Creation is a private affair.

When, four flights up, you knock at the door of his Dartmouth Street studio, the voice says “Wait a minute”: inside, a canvas is taken down and turned to the wall, the door slides open, and brown eyes contemplate one from a serious and secret face. Then in an extraordinary transformation, the whole face changes with welcome. Thus Hyman Bloom introduces you to two Hyman Blooms, and there may be others that I have not yet met.

The two Hyman Blooms share a face of extraordinary mobility. Its most stable expression is one of rapt and brown-eyed seriousness, with the glance reflectively sidelong, as if he were slightly distracted in listening to you by the duty of keeping a third interior eye on his own thoughts. From long practice, he does this so well that he achieves the impossible. He is the only person I know who can be warmly remote. But produce a thought that fascinates him and his face breaks into all kinds of fluid and responsive attention, and expressions chase each other across his face like whippets of wind across a pond.

He talks in a low, slightly-hurried voice, with soft edges, that forces his listeners to incline toward him, so that they become included in his isolation, and separated from the rest of the world. Such meetings often take place over a table in a Greek restaurant, to which he unerringly leads you through twisting back streets. He has a repertory of restaurants which he catalogues on his fingers as he gives you a sort of phantom choice before he selects the one for the night himself. If a large party has joined him for dinner, he takes, when the check arrives, a piece of paper from his pocket, puts horned-rimmed glasses on the end of his nose, mimics a usurer for a moment, and then most seriously begins to separate individual accounts out of the total bill in front of him. He always gets it right.

Walking with Hyman always gives me a feeling of potential, as if something extraordinary were going to happen in a prosaic Boston street. He walks as if the next buoyant step were going to lift him. I always have the impression that someday, with no surprise at all, I will see him walk up step by step from the street beside me, on some invisible staircase of air.

He was of course, marked from the start, when Harold Zimmerman, a Boston artist with strong theories about teaching, found two young geniuses (Jack Levine was the other) in Boston’s rough South End. Zimmerman was a teacher of almost military discipline, and he insisted on an exacting training of drawing from memory after intense observation. It is discipline that marks Bloom to this day. So much so that the presence of a model before him can still induce a sort of paralysis. For him the gap between observation and creation is a highly gestatory interval, during which a great deal of hidden machinery is silently turning over.

I once asked him to do a tiny picture, with one condition. I would supply the model—a dried-up old apple of which I am very fond. Then the fun started. Hyman delights in this sort of ridiculous dialectic.

“If I’m to paint an apple,” he said, “you must allow me the freedom to paint it as I wish.”

“Full freedom. All I want is the apple.”

“Do you want it alone or with something else?”

“I don’t mind. That’s up to you.

“I don’t know if I can really express myself in an apple.”

“Well, you like Caravaggio’s moth-eathen apple.”

“What sort of an apple would you like? A cubist apple maybe? Or a futurist apple?”

”Just my apple. Only you must paint it from life.”

“From life?” said Hyman, with mock apprehension, “do you want to destroy me?”

This is not as funny as it sounds, however, for Hyman’s inner eye surrounds any artistic problem with a number of intensely vivid images, which his capacity to visualize calls up with almost eidetic force. His very fertility of invention and the possibilities he confronts diminishes his output.

Zimmerman’s influence was complete for about six years, until Hyman was 19. Then he and Levine were taken up by one of Boston’s great pundits in the Fine Arts, the late Denman Ross who had been long associated with the Fogg Museum, an institution perhaps justified in taking itself so seriously. When Hyman met Ross, he was Professor Emeritus at Harvard, a man who behaved grandly in the great tradition of patronage. He hired a studio where Zimmerman could instruct the two boys, and after their graduation from high school gave them each an allowance of $12 a week. Ross also gave them the benefits of a theory of color he had developed, through which precise effects could be repeatedly achieved by a strict limitation of means. Thus color could be manipulated like the notes of a musical scale, and complex effects produced by simple combinations. He also introduced them to Oriental art and to the Old Masters and their drawings which the two youngsters studied avidly. They developed a formidable respect for tradition.

Bloom’s early drawings under Zimmerman are young master drawings and, like the glass flowers at the Peabody Museum, they are among the major Boston phenomena. They are incredible achievements for a young boy with resilient sureness of line and a facility that is breath-taking. Often of metamorphoses fixed in transition, they are metaphysical weddings between fact and fancy performed by an introverted, almost painfully sensitive imagination. They remind you of that middle air where many of William Blake’s apocalyptic figures spend themselves. I remember one drawing of a bull or animal with human head, like the beast in Yeat’s poem, shambling towards Bethlehem to be born.

During the years with Ross the broadly civilized professor tried to make a humanist out of bloom but he was a mystic manqué. I have on occasion met him, with his dark inscrutable face, drifting through the Twilight, a slim figure that looks as if you could step into a Zurburan and look quite at home. His is a Spanish sort of mysticism, and I can imagine him contemplating seriously one of those miracles of the liquefying blood.

It was around 1943 that he paid that strange historic visit to the autopsy room at Kenmore Hospital and contemplated the human fragments so pitiful exposed. As he looked at them the silent marriage between paint and subject took place in the imagination, and out of this mysterious moment some of his greatest pictures were born, many of them years later. In that one confrontation, he studied the sheen of fascia and tissues watched the rapid color changes in exposed viscera, and stocked that avid memory of his with all their subtle changes against the exposed field of red. Many years later he was to return to the autopsy room, this time at the City Hospital, to satisfy an anatomical curiosity. He remembers the doctors were often surprised at autopsy when they discovered the cause of death.

He has searched then, with surgical devotion among the chasms and abysses of viscera, like some materialist for a physical coordinate of pain or for some ultimate metaphysical abstract, like meaning. Although meaning, like knowledge, is something he finds that continually recedes with greater understanding. But it is a rich journey

I said Hyman Bloom was a mystic materialist. It would be more correct call him a materialistic mystic. He is a painter and the materialist comes first. For all his spirituality, the fingers that hold the brush are full of animal heat. Most Anglo-Saxon painters are chastely wedded to their paint. Hyman bloom has had a most erotic affair with it. He mixes his own paints with greatest love and care.

During a walk through a gallery, it is always the warm, running juice of paint that has clotted in to a glistening passage that attracts his eye like a magnet. He finds this in the most unlikely places. I remember being with him when he stopped to put his nose close to a jewel-like glaze of paint in a Diaz, inspect curiously the raised eruptions in a Mancini canvas, looked hard at a passage in a Millet which out-shown a Delacroix beside it, and shook hands in his own mind with the 19th century American painter named Cropsey, for his juicy autumnal reds.

Predictably enough, his favorites have included those who traditionally mix blood with their paint – Roualt, Soutine, Rembrandt, Kokoschka. His other confrontations include Blake, Redon, and a little known fantasist, Manzu Desiderio. These are two lines of painting, two divisions of men, and two states of mind perhaps in Bloom: his paintings bring them together.

But to go back to bodies. Like Baudelaire, Bloom is fascinated by the erotic beauty of decaying flesh and the sensuality of the attraction in repulsion. He delights in finding a subject that makes sort of a plexus through which such contraries can move in and out, like breath, and restore the spirit what is become inanimate. I always consider Bloom a religious man, and for many years his Cathedral was roofed by the Gothic vault of the rib cage that covers man’s most intimate vitals. His act of creation has often taken place among maimed and exposed and glistening entrails.

He doesn’t talk about art – mainly because it has little to do with art. It would be like him to say that no one tries to explain John Donne in terms of painting. Nor does he think a painter should be under any obligation to talk about art. I once asked him to talk about his pictures with me on television. He ran off immediately on a semantic journey thorough corridors of allusion, suggestions, and explanations through which I clumsily followed as best I could. It was like being hit by battalions of reeling shadows, as if the sun had suddenly accelerated in the sky. I finally deciphered all this as a refusal. Although he did have a suggestion. He suggested that I resurrect Ingres and Delacroix. “Conflict, you know” he said, “you television fellows like conflict.”

His enthusiasms are for music rather than words. And outside his door you are liable to pause to hear the single note of an Indian flute being put through a progression of adventures. Carefully, and with much love, he takes from special cases sitars and ouds and vinas, stringed and bulbous, and he draws from them the wayward rhythms and subtle dissonances of Indian music, his head bent toward the instrument as if he and it were having a conversation. Over 20 years ago in Boston, he watched the Indian dancer, Ouday Shakar, perform to music that was later put out in an album by RCA Victor. The Hebrew music that had surrounded his childhood had given him and ear for it, for there are similarities. Hyman speaks most feelingly of Indian music as the melodic line in the void. It is a frail bridge across which hope and dreams pass and die, are submerged and lost, then found again. This perspective of the human odyssey against the void is one that attracts him, for his art is based on a similar perspective.

He is willing to talk about music endlessly. I remember one more memorable sight of such a conversation — Bloom and the composer Hovhanis in conversation in a Greek restaurant. Hovhanis, lank and prickly and bearded, inclined cross the table like some kyphosed crane toward the shave Bloom — a satyr in earnest conversation with a Jesuit.

Once we got lost in a Museum and Hyman said

“Why are museums so big?”

“Because fellows like you keep painting”

“If it were only me,” said Hyman, “it would be a very small museum.”

He paints very slowly. And part of the mystery of Hyman Bloom is the disparity between the huge total of hours he spends behind the closed door of his studio, and what comes out in the way of painting. He gets to the studio late in the morning and continues until early in the morning, and I am sometimes haunted by the idea that he is inventing a new alphabet, or digging a tunnel that will come out between the railway tracks outside or playing planchette with the skeleton whose skull rests on a shelf. He denies that his creative parturition is excessively painful. He has no difficulty in finding a subject, and he has chosen a definite repertory of subjects—chandeliers, buried treasure, brides, mediums, seances—because he feels that these are subjects that can reflect his total preoccupation with life and art. The painting is for him a palpable flash of insight, layered and encrusted with paint, thrown off from some complex circulating logos. The only problems are the painter’s problems, finding the shapes and colors which trap the vagrant spirit. I once quoted to him the remark that mystics make bad painters. He replied that the mystics’ preoccupations are the great subject for art.

His studio is a large, low-ceilinged room inhabited by an extraordinary collection of objects. A skull without a mandible still manages to smile from a shelf: not far away is a photographer’s 8-by-10 camera on a tripod. In a corner behind it a dried fish’s head hangs from a string, the naked skeleton trailing out of it like a bony feather; there is a row of tools hanging up; an elaborate recording-machine in another corner; a photograph of a Bronzino young man; beside it, Bresdin’s print of the Good Samaritan. There are dried-out leaves and flowers, still and brittle with decay, that would shatter at a touch. A branch covered with moss looks like a bewigged arterial tree against the whitewashed wall. Near it are some plaster masks he has made himself and a cast of an aged, female hand. Hyman shows you some dog-skulls, and sights through the snout to show the hanging curtains of bone, like tissue-paper. In a corner are some faded gourds, knobbly with nodes, as if they had leprosy. Hyman likes to gather them when fresh and watch with curiosity as they go through their shimmering mutations of color. He is fascinated by the waxing and waning of organic life, as if such outward changes can lead the mind inward to the mysteries of flux and development. If he happened to bruise himself, I’m sure he would watch it change from blue to violet to indigo and ochre with the same fascination. Scattered here and there in the studio are other paraphernalia and incunabula of his vision—fossils, shells glowing with tiny concentric rainbows. All that glistens takes his eye.

Hyman was seven and one-half when he came to this country from Latvia, a place so fertile of American painters that Russia, if it has a mind to, can claim to have invented a great deal of contemporary American painting. His earliest memories of Latvia are vivid and shocking. This was during and immediately after the first World War, and to the young boy the facts of war had little to do with the ideas behind it. There were, he remembers, Germans and two types of Russians, and what he saw left him with a violent antipathy to all ideas of progress by physical violence. The human animal is an instrument of profound evil and profound good, and the mystery is impenetrable. Morally he is a realist, and partly stoic.

Practically, this has occasionally worked out as a negativism that was once a legend among other painters. Loren Maclver, herself a retiring and sensitive person, once planned a surprise birthday party for Hyman, to which be responded with surprise all right. Then with dismay he watched himself, holding in one state of mind contrary emotions of pleasure and displeasure, batten down all the hatches and refuse to participate. Years later, he confessed that he had wanted to break his silence and join in. Since I heard this story, I select the most dreadful birthday card I can find each year and send it to him.

Through the wry facade of irony and the thorny thickets of wit one can see some large convictions resting uncompromisingly, like boulders. He expects nothing from the world, and expecting nothing, owes it nothing. He has nothing to do with schools or fashions or popular causes. He is suspicious of the doubtful blessings of professional success, and the pater nosters of directors and dealers. He has the creative artist’s respectful contempt of the scholar, and the creative artist’s mistrust of the critic—with Hyman, an indulgent mistrust; I rather think I could find in him a belief that paintings are, for critics, modified Rorschach tests in which the critic always discovers himself, and may stumble across the painter by accident. He also extends his contempt to those artists whose favorite topic is the insensitivity of the patron and purchasing fund to their work. The expectation of success is to him a vulgarity. One is not ultimately judged by ones contemporaries and one’s contemporaries don’t matter very much. He is the only artist I know who doesn’t care if the abstract expressionists win or lose. Win or lose has nothing to do with art. His perspectives are awesomely wide, and it is this that makes him seem like some astronomer watching his thoughts circulate like planets. It is this that absorbs all bitterness and leaves only a wry irony.

One Hyman Bloom is, then, a dedicated epistomologist of the visceral and the metaphysical. He is in constant search for the system that makes the moment of visionary illumination fall into place in the larger framework of a life. Most people have experienced moments of heightened awareness which promised deeper fulfillment, and for Hyman it is these moments which must be made always accessible through a personal system. Such moments of vision, or awareness, or insight, become the axis around which a system begins to revolve. But against this background of deeper search, his mind has a limber and agile wit, and he is a shadow-master of verbal charades. His jokes are always a bit like a condemned man’s. They are immediately brilliant and make you laugh. A day later, the laugh has seeped into the void and one has a glimpse of the rather terrifying spaces and distances in the mind that can make such jokes. If he has a Jesuitical head, with brown hair the color of a cowl, he has also the Jesuitical gift of dialectic. Thus every statement is quickly teased out into its reductio ad absurdum. He brings all seriousness to the abyss of jest. It is almost frightening, for it is Godot-like in its sense of paralysis.

He seems to find his affirmation where facts are reduced to echoes. When with him, the safe world may suddenly lose its bottom and leave you treading air. He riddles every seemingly solid fact out of existence, and leaves it suspended among a wilderness of mirrors. He surrounds the fact with so many points of view that our eyes are distracted from the fact to the many ways Hyman sees the fact. A great deal of Hyman’s life has been dedicated to the conquest of many points of view around the same fact. To test an invented point of view, and make it solid and accessible to others through his art is to him a major achievement. Perhaps the slow struggles of his painting are an attempt to make the unsubstantial world solid again, and to synthesize life’s fragments as he wishes, into the coherent and wordless language of painting.

– Brian O’Doherty