I. The Artist as Chandelier: An Introduction to Bloom’s Visionary Aesthetics

I would like to thank Edward Shein for this kind invitation to participate in the symposium, Robert Alimi for his collegial conversations and his help with visual materials, Stella Bloom for generously making available the contents of the artist’s sketchbooks and library, Erica Hirshler for her work in assembling this amazing exhibition and symposium, and Kristen Hoskins and Liz Battey for their assistance with the event.

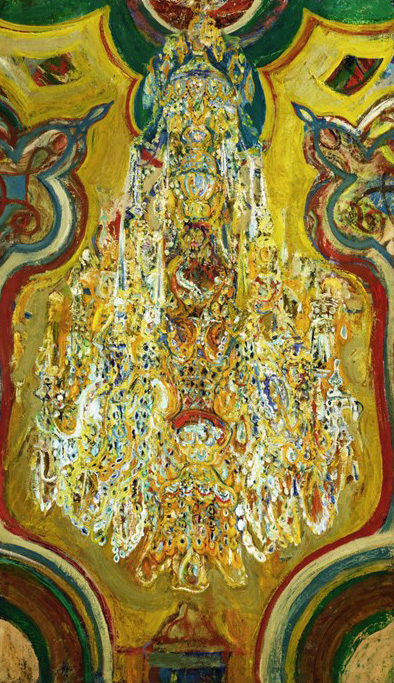

Soon after I started to engage deeply with the research materials for the book project Modern Mystic: The Art of Hyman Bloom, I began to think of Bloom himself as a very special kind of “chandelier”. This symbol became something of a running joke as I chatted with the core members of the team, with Ed Shein and Bob Alimi, about Bloom’s visionary modernist project. And, the more extensively I engaged with Bloom’s artworks, the more vivid the image of the chandelier became as a metaphor for the artist’s creative practice, and for the distinctive type of spirituality that underpins his contribution to mid-century modernism.

We’re fortunate to have a striking example of an actual Bloom chandelier painting on display in this exhibition; Chandelier II, of 1945.

Okay, so, why a chandelier? Because this object provides a vivid metaphor for envisioning ever-shifting constellations of luminous presences. And that, too, is Bloom. Despite the differences between the subjects he depicted and the various stylistic modes in which he worked, Bloom’s oeuvre can be approached collectively as an intricate configuration of prisms, a conglomeration of dynamic, shifting frameworks that produce a host of luminous perspectives. In this painting, as in so many of Bloom’s images, fragments of everyday life become transfigured so that they appear to be radiant. In turn, Bloom’s transformational vision creates a sense that viewers are inhabiting an illuminated reality. Thus the expressive image of the chandelier provides something concrete to hold onto as we examine some of the more subtle and esoteric aspects of the artist’s engagement with mystical spirituality.

II. What Bloom Read

First, it’s important to note that Bloom was a voracious reader and a constant explorer. He was fascinated by the study of comparative religion, as well as by various esoteric philosophies and spiritual systems. Notably, Bloom did not adopt an orthodox approach to any particular tradition. Instead, he engaged a number of eclectic sources quite broadly, and he found novel ways to make them his own.

Bloom was born into an Orthodox Jewish family who left their village on the Lithuania/Latvia border to settle in Boston in late 1920. While Bloom made his Bar Mitzvah—and later, he requested a traditional Jewish burial—the artist lived his adult life as a culturally assimilated Jew.

At an early point in his career, Bloom painted groundbreaking images of The Synagogue. Here I show you an example from 1940, and you can see a chandelier hanging in the background. As Bloom later noted, he was drawn to what he saw as the ecstatic moments within sacred rituals, particularly as voiced in the exquisite songs of the cantors. In addition, throughout his career Bloom produced elaborate paintings and drawings of rabbis holding Torah scrolls, or being deeply immersed in the contemplation of sacred texts. Extending these themes, the Jewish mystical tradition of Kabbala also informed Bloom’s thinking, not because the artist identified as a Kabbalist per se, but because this esoteric system figured prominently in the Theosophical texts that Bloom engaged so deeply. Just as Theosophy represented the great synthesizer of systems, one of the most influential books that Bloom encountered was Helena Blavatsky’s multi-volume compilation, The Secret Doctrine: The Synthesis of Science, Religion, and Philosophy (1888). Notably, Bloom read these volumes during the summer of 1939. Blavatsky’s hybrid, compendious works provided elaborate conceptual frameworks of esoteric terms and symbols, which she often approached from a comparative perspective. This, in turn, allowed Bloom to correlate multiple systems of thought, including Kabbala, Hinduism, and Buddhism.

Bloom was particularly intrigued by the images of the “wheel of life” and the “wheel of existence”. He found suggestive thematic resonances between these perennial images and the classical motif of Man Breaking Bonds on a Wheel of 1929, which he depicted in an elaborate crayon drawing that is featured in this show. Here you see the image, and a detail. For Bloom, the wheel also functioned as a means to express recursive cycles and circular formulations of temporality, including in the calendar and in the wheel of the zodiac, imagery that the artist developed extensively in his sketchbooks. In the late 1930s, Bloom visited Boston’s Vedanta Center; Vedanta is a form of Hindu philosophy. In Hinduism, the wheel refers to notions of fate and rebirth, existence and recurrence, as well as the chakras, or spinning wheels of luminous energy embedded within the energetic or subtle human body. In Buddhism, prayer wheels relate to sacred practices in which wheels are spun continuously to engage the blessings of a spiritual being who is thought to be the embodiment of compassion, thereby awakening the spiritually powerful sense of compassion that resides within the higher self of human beings.

Such notions of compassionate avatars, or bodhisattvas, held considerable appeal for Bloom. The artist painted these transitional figures in Theosophically-inflected paintings such as The Medium, which you see here, and Apparition of Danger. Both date from 1951 and they are now housed in the Hirshhorn Collection in Washington, D.C. As was the case for Bloom and others, the study of Eastern religions in America represented a compelling means for cultivating a comparative, cross-cultural perspective. These traditions provided complementary ways of approaching notions of compassion and suffering, as well as insight into a phenomenon that scholars refer to as theosis. Theosis is the process through which human beings become godlike as they consciously recognize their own inner divinity. Esoteric Buddhism in particular provided Bloom with an enhanced understanding of related Bodhisattva imagery, as these transitional figures of wisdom and compassion manifested as incarnated, human-like divinities.

Yet the seeds for these spiritual explorations were evident at an early point Bloom’s life. As a young man, the artist read the metaphysical poetry of William Blake, and he engaged the mystical texts of William James and P. D. Ouspensky, particularly the latter’s Tertium Organum: A Key to the Enigmas of the World. Bloom attended meetings at the Boston Society for Psychical Research and at the Order of the Portal, an esoteric group that discussed various occult subjects. These formative experiences provided Bloom with open doorways of thought, as well as with robust comparative frameworks for approaching various topics in mysticism and Esotericism. Moreover, these experiences provided the young artist with a means to build a community, to engage in thoughtful discussions, and to consult specialty libraries. Later in life, Bloom also experimented with Spiritualism. He attended séances, and he created elaborate drawings inspired by these mystical subjects. Indeed, mediums provided suggestive motifs for envisioning multiple, transitional worlds.

III. What Bloom Saw

Each of these practices and traditions can be seen as a constituent element within Bloom’s composite vision, or, as an individual crystal within his metaphorical chandelier. While all were important, arguably, no single experience was as impactful as the mystical experience that Bloom had in 1939. Notably, this event followed a period of extended darkness and struggle in the artist’s life. Here, Bloom’s own words are crucial. As the artist recalled: “I had a conviction of immortality, of being part of something permanent and ever-changing, of metamorphosis as the nature of being. Everything was intensely beautiful, and I had a sense of love for life that was greater than I had ever had before.” This encounter was accompanied by a sense of “dazzling color” that transformed Bloom’s view of the world around him, a vision that united mortal flesh with a sense of transcendence. As Bloom further observed: “Spiritual life cannot be delegated; true spiritual experience can only come from within, and it is only through individual effort to deepen the process that a state of grace can be achieved. Certain kinds of knowledge can only be earned, sometimes through effort, and sometimes through suffering.”

IV. How Bloom Made This His Own

Now, let me provide you with another way to envision the ways in which Bloom represented his mystical experience. In addition to the chandeliers, another hallmark image in Bloom’s oeuvre is his evocatively titled Self-Portrait of 1948, a painting that is also featured in this exhibition. When viewed in light of Bloom’s description of his mystical experience, Self-Portrait can be seen as instantiating the ways in which aesthetics can function as a language of epiphanies. In this numinous corporeal image, Bloom presents an alternative anatomical display, as flayed human flesh converges with the prismatic spectral body to produce a configuration of colored light.

These physical and metaphysical themes are consistent not only with Bloom’s mystical experience, but with his practice of attending the actual dissections of cadavers in hospital morgues and anatomy labs.

And here you see Bloom’s contemporary painting Female Corpse, Back View of 1947.

This painting is not only featured in the exhibition, but it is part of the permanent collection of the Boston Museum, a wonderful Lane Collection piece. Indeed, Bloom’s groundbreaking autopsy and dissection images represent the focus of this exhibition, Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death. Throughout these pieces, Bloom’s visionary modernism appears within an artistically progressive, abstracted framework of human figuration. The result is an expressive form of mystical humanism.

Indeed, these works are remarkable for many reasons, not the least of which is because they feature a highly stylized, abstracted imaging of the anatomical forms that Bloom encountered in an actual clinical context. In so doing, the paintings engage a series of ritual boundary crossings, just as they present transgressive and otherwise-unseen subjects through a language of iridescent, translucent forms. Thus the images appear to be at once real and otherworldly. They are figural and abstract. They are bodies, and they are not bodies. They are individuals, and they are collective typological presences. In short, Bloom is having it both ways, as he moves beyond conventional dualistic categories. The logic that underpins these images is at once mystical and nondual. The anatomical images both violently and gracefully incorporate the two sides of being. In these works, Bloom is painting subjects that are coming into form, and that are going out of form, simultaneously. Thus he is painting the creation, that is the destruction, that is the creation. All of which is to say, in these works, Bloom can be seen as painting mysticism itself. When viewed in this light, Bloom is not painting ABOUT mysticism. He’s PAINTING MYSTICISM. This is both eye-opening and mind-blowing.

Once again, the artist’s own words are significant. As Bloom observed of his encounters in the anatomy lab: “On the one hand, it was harrowing; on the other it was beautiful—iridescent and pearly. It opened up avenues for feelings not yet gelled. It had a liberating effect. I felt something inside that I could express through color. As a subject, it could synthesize things for me. The paradox of the harrowing and the beautiful could be brought into unity.” Just as he engaged the paradoxical language of “the harrowing and the beautiful”, Bloom adopted a nondual perspective as he recalled his encounters with the vicissitudes of death and of life itself.

Not surprisingly, Bloom’s anatomical works were controversial, both historically and culturally. As a result, the artist repeatedly found himself in the position of defending the motives underlying his engagement with these difficult subjects, while simultaneously encouraging viewers to look beyond their conventional difficulties. Thus in an April 1954 interview in Time magazine, Bloom observed of these challenging pieces: “It seems to me that if you have any conviction of immortality you can look at such a subject as objectively as at anything else. The body is very beautiful, and its insides are just as beautiful as the outside.”

In short, as Bloom fused his composite mystical vision with his innovative modernist artistic practice, he deeply explored the premise that, ultimately, there is nothing that cannot be seen, and no place where vision cannot go. Now, this does not mean that these complex artworks are easy to understand, or easy to look at. Sometimes, when we encounter Bloom’s monumental canvases, the light comes into our eyes so strongly that we almost cannot see. It’s a bit like looking directly into a chandelier, and trying to sustain our gaze amidst an abundance of shifting light. Yet Bloom found this light within the darkest of places, so that creation and destruction became fused within an ongoing dynamic of expressive transformation. Again and again, Bloom shows us the shattering, that is the creation—the release that produces displays of otherwise hidden light.

Or, to phrase this mystical insight another way: As we look at paintings as different and as similar as Chandelier II and Self-Portrait, a shared question arises, namely: How do we know, understand, and find language for the part of humanity that encompasses and transcends the forms of the physical body? If you take away nothing else from this talk today, this is the insight I’d like you to have, so I’ll repeat it as a kind of open-ended question to which Bloom’s paintings provide one remarkable response. Namely: How do we see, know, understand, and find language for the part of humanity that encompasses and transcends the forms of the physical body? As the artist himself recognized, both trauma and grace can serve as powerful tools for cultivating an expanded perspective on the relations between humanity and spirituality. And that is the subject of our symposium today: “Hyman Bloom: Spirituality and Art”.

V. Conclusion: Bloom as a Case Study in How Vision Can Inspire Vision

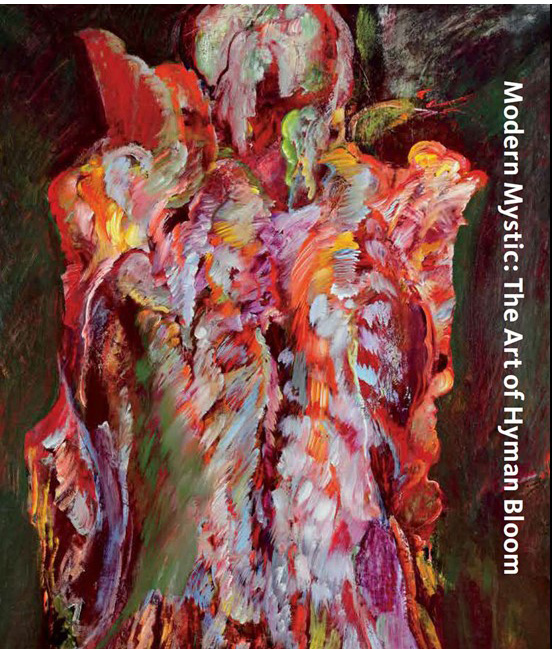

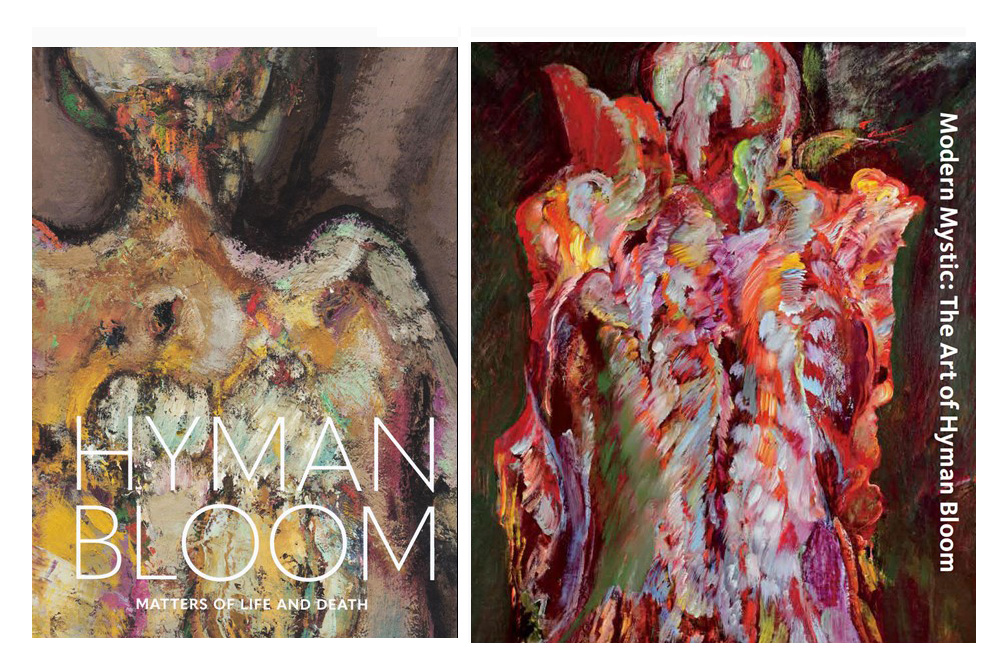

Left: Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death (MFA Publications)

Right: Modern Mystic: The Art of Hyman Bloom (Artbook/DAP)

I’ll conclude by emphasizing that Bloom occupies a singular position within the history of modern art. Again and again, his works display a dynamic of facing death and seeing life. The artist approaches these ultimate subjects in a unique and remarkable way. Not only is he a treasure finder, but he’s someone who makes these treasures visible for all to see.

The Boston show, Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death, its accompanying catalogue, and the monograph Modern Mystic: The Art of Hyman Bloom, invite viewers to consider not only Bloom’s unique artistic career, but larger, collective themes concerning visibility as they unfolded culturally and structurally, historically and presently, visually and spiritually. Bloom’s works repeatedly ask us to consider what it takes to make something visible that would otherwise remain unseen. This exhibition, the catalogue, and the monograph allow Bloom’s works to be seen collectively, and to be seen in new ways. In short, these subjects represent nothing less than an extended meditation on how vision can inspire vision. And this too is appropriate, because it represents the core of Bloom’s mystical vision, as well.

Marcia Brennan is the Carolyn and Fred McManis Professor of Humanities, and Professor of Art History and Religious Studies, at Rice University. She is also Artist in Residence in the Department of Palliative Care and Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center. Her research areas include modernist aesthetics and curatorial studies, clinical aesthetics, and the medical humanities; she is the author of numerous books in these areas.

NOTE: Full video of the Hyman Bloom: Spirituality and Art Symposium can be viewed on the MFA’s YouTube channel.