The Spirits of Hyman Bloom: The Sources of His Imagery (excerpt)

by Dorothy Abbott Thompson

© The Estate of Dorothy Abbott Thompson. Reproduced with permission.

Among the many people who worked at the Mirski Gallery from time to time were the Swetzoff brothers, Hyman and Seymour. In 1948 they decided to open a gallery of their own, which began as the Frameshop Gallery on Huntington Avenue. In 1953 Hyman Swetzoff became the director and moved to Newbury Street, where the Swetzoff Gallery remained until his death in 1968. Swetzoff was urbane and charming. He was well educated, spoke French, translated French poetry, and wrote poetry of his own. He wrote critical articles about Redon and Bresdin and was, generally speaking, more intellectual in his approach to art than Mirski. He was widely considered to be the most knowledgeable and erudite of the Newbury Street dealers, the one with the most discerning eye. He was particularly a connoisseur of prints and drawings, and brought works by many masters of those media to Boston: Kathe Kollwitz, Gustave Klimpt, Egon Shiele, Odilon Redon, Rodolphe Bresdin and James Ensor, among others. The gallery also showed the work of Boston artists such as Jason Berger, Robert Eshoo, Alcalay Boghosian, Harold Tovish and Gyorgy Kepes.

Among the many people who worked at the Mirski Gallery from time to time were the Swetzoff brothers, Hyman and Seymour. In 1948 they decided to open a gallery of their own, which began as the Frameshop Gallery on Huntington Avenue. In 1953 Hyman Swetzoff became the director and moved to Newbury Street, where the Swetzoff Gallery remained until his death in 1968. Swetzoff was urbane and charming. He was well educated, spoke French, translated French poetry, and wrote poetry of his own. He wrote critical articles about Redon and Bresdin and was, generally speaking, more intellectual in his approach to art than Mirski. He was widely considered to be the most knowledgeable and erudite of the Newbury Street dealers, the one with the most discerning eye. He was particularly a connoisseur of prints and drawings, and brought works by many masters of those media to Boston: Kathe Kollwitz, Gustave Klimpt, Egon Shiele, Odilon Redon, Rodolphe Bresdin and James Ensor, among others. The gallery also showed the work of Boston artists such as Jason Berger, Robert Eshoo, Alcalay Boghosian, Harold Tovish and Gyorgy Kepes.

Swetzoff admired Bloom’s work and supported him enthusiastically, creating a market for his small notebook drawings, selling his work, and advancing him money when he needed it. Bloom occasionally traded his own drawings for prints by Redon and Bresdin. Swetzoff had introduced Bloom to Bresdin’s small, dense etchings with their teeming, leafy landscapes and curling clouds, and in these mysterious landscapes, suffused with an air of anxiety, Bloom found images mirroring his own perceptions of nature as more threatening than sheltering. Eventually he incorporated this influence into his own large landscape drawings of the 1960s.

The gallery was popular with the intellectual and artistic community of Boston and Cambridge. Serge Koussevitzky and Leonard Bernstein were frequent visitors, as were many artists and collectors. A Boston businessman, Jerry Goldberg, was a frequent visitor who bought work regularly. Goldberg shared with Bloom a common origin in West End. He had left home in his late teens and spent his twenties in footloose travels. When his wanderlust subsided, he returned to Boston to work as a jobber in the clothing business. He married and had a family and gradually developed the business into an enterprise that provided a comfortable bourgeois existence for him and his wife and two children. As he grew more comfortable financially, his wife, Sophie, undertook to reflect their prosperity by redecorating their house. To find the painting she wanted to hang over the sofa, she persuaded her husband to go with her to the Swetzoff Gallery. It was an important visit for both Goldberg and Bloom. It was in 1954 just before the retrospective of Bloom’s work at the Institute of Contemporary Art, and Swetzoff had a group of Bloom’s small notebook drawings out to show visitors. Goldberg was immediately attracted to the drawings, bought one, and sought out the artist. It was an exciting moment for him. He had discovered art and Bloom became his guide and mentor in his new avocation as a connoisseur and collector. Both men, products of an immigrant Jewish culture, had relatively little formal education, and each was a somewhat rootless and solitary person; they found the greatest companionship together through their mutual love of art and the comfort of a shared background. Goldberg and Bloom met every Saturday for lunch, then visited the galleries on Newbury Street, watched by the curious for clues about what they thought was important—what to like and what to buy. Goldberg, having discovered art, was always buying, always owed money, and relished his role as a patron. He formed a distinguished collection in the process and extended his support of Bloom to include a stipend, which he continued to provide until his death from cancer at the age of 53 in 1965. His daughter, Judith, described the relationship as one in which he felt in some awe of Bloom, and believed, as did others who are scattered through Blooms life, that it was his special privilege to support his creativity. Bloom painted several portraits of him; a final one, unfinished when Goldberg died, was put aside and never worked on again.

Bloom’s career was advancing steadily. In 1949 the Carnegie International included his painting The Bride, which Alfred Frankfurter described in Art News of December of that year as “as lyrical and beautiful a tragedy complete in pictorial terms as anyone could today paint.” In 1950 Frankfurter selected Bloom for inclusion in the Venice Biennale with the painters Rico Lebrun, Arshile Gorky, Lee Gatch, John Marin, Willem de Kooning and Jackson Pollock. The Americans were seen as the descendants of Gauguin, Van Gogh and Redon through the Fauves, Kandinsky and Klee, and the Americans Dove and Tobey. Though to some extent schools had already been defined and titles given, which would assign some of these artists to “correct” positions and leave others on the “wrong” path, the art world was not yet dominated by the authoritarian voice of formalist criticism. For all the differences that separated them as artists, Pollock, de Kooning, Gorky and Bloom shared emotive and painterly qualities that were clearly demonstrated when their paintings were shown together. Inclusion in such an important exhibition only eight years after Bloom’s work was first shown in Americans 1942 was evidence of the rapidity with which his career was developing.

Art News of January 1950 carried a sympathetic essay about the artist by Elaine de Kooning. In “Hyman Bloom Paints a Picture,” de Kooning, a painter herself, insightfully identified a crucial characteristic of Bloom’s work.

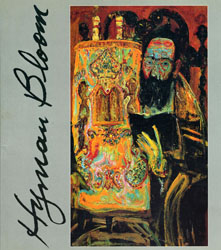

A rabbi, remote in grand proportions against an incandescent wall, a chandelier cascading in cut glass pendants from the ceiling of a synagogue, or a disemboweled corpse lying on an autopsy table—the subject of a fainting by Hyman Bloom is as inseparable from its physical aspects as is the work of Griinewald or Rembrandt. Like these artists he seems to think with his brush; complex philosophical implications are conveyed in the act of painting.

This was precisely the quality of Bloom’s work that attracted such painters as Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Franz Kline. He was increasingly admired for the poetic richness he achieved by the unity of materials, technical means and emotional and philosophical content.