Color and Ecstasy in the Art of Hyman Bloom

by Isabelle Dervaux

The artist’s reward is pleasure, ecstasy from contact with the unknown. Hyman Bloom1

All art deals with intimations of

mortalityimmortality Mark Rothko2(amended by Hyman Bloom)

In one of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short stories, a poor Jew comes to the rabbi on a Sabbath evening with an unusual request: may a man sleep with the corpse of his dead wife? The “gruesome question” — it is the title of the story — comes as a shock among the rabbinical court gathered at dusk to ponder the mysteries of the Torah. In the midst of these lofty preoccupations, in the “atmosphere of wonder and miracles” suggested by the stars and moon rising in the sky, the problem of the poor man whose wife’s body is threatening to be eaten by rats — that’s why he must place her corpse on his bed — strikes an unexpected note.3 Such a combination of spiritual concerns and harsh realism, typical of Singer’s tales, is also at the core of Hyman Bloom’s art. From their common background in the Eastern European Jewish community, Bloom and Singer have created parallel worlds populated with rabbis, corpses, brides, spirits, and demons — colorful worlds in which the familiar and the supernatural come together in the expression of a wider cosmic order.

While Singer exploited the success of his first stories published in the United States in the early 1950s to develop a popular style of Yiddish-American literature, Bloom, more introverted, remained aloof from the art scene and pursued his artistic career in relative isolation. Although he is usually associated with the so-called Boston School of Expressionism, which also includes Jack Levine, Karl Zerbe, and David Aronson, Bloom was never part of any organized artistic movement. “Hyman Bloom was unique among us”, artist and critic Lois Tarlow recalled “He guarded his privacy and his time. He seldom went to openings, even his own, or hung around with other artists for mutual support and admiration.”4 From the beginning, Bloom was reluctant to show his paintings to anyone. When the curator of The Museum of Modern Art, Dorothy Miller, wished to see Bloom’s work for a group exhibition she was organizing in 1942, she had a hard time persuading him to show her his paintings and lend them to the museum.5 The thirteen paintings she included in the landmark exhibition Americans 1942, the first works by Hyman Bloom ever shown in New York, launched his reputation. In 1950, Bloom was one of seven artists (including John Marin, Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock) selected to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale. Bloom’s fame culminated in 1954 with a retrospective at the Whitney Museum. Although his drawings were again the subject of an exhibition at the Whitney Museum in 1968, by then Bloom’s commitment to figurative art was keeping him on the margins of mainstream American art. In revisiting his work in 2002, however, it is striking to see how his obsession with death, the macabre, and the spiritual is relevant today, and how much it relates to the art of the last two decades.

"TO FOLLOW THE MOVEMENTS OF THE IMAGINATION"

The son of a shoemaker and a seamstress, Hyman Bloom was born in 1913 in the village of Brunoviski, on the border between Latvia and Lithuania. At the age of seven he emigrated with his parents to America, where two older brothers had preceded them before Bloom was born. Growing up in Boston’s West End neighborhood, in a familial atmosphere fraught with tensions as each generation coped differently with the difficulty of adaptation to a new country, Bloom shared the experience of many artist immigrants of the twentieth century.6 Like Arshile Gorky or Mark Rothko, he suffered throughout his life from a feeling of displacement and alienation. At the age of thirteen, after celebrating his bar mitzvah, Bloom turned away from the strict Orthodox faith in which he had been brought up. This was the beginning of a spiritual awakening which took him from Spinoza and Eastern philosophy to a profound involvement with an array of mystical and esoteric systems of thought, including theosophy, astrology, and the occult. In this metaphysical quest, art came to play a fundamental role. For me,” Bloom explained, “paint and thought amount to the same thing, or at least they have a goal in common. They are an attempt to cope with one’s destiny and become master of it.”7

Bloom began drawing earnestly at an early age. When he was in eighth grade, he attended classes for talented students sponsored by the municipal school system at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. He also enrolled in drawing classes at the West End Community Center, taught by Harold K. Zimmerman, whose unusual teaching method had a major influence on the young Bloom. Eschewing the traditional use of plaster casts and models, Zimmerman instructed his students to draw from memory and imagination. They were encouraged to examine paintings and drawings in local museums, to study books of anatomy, and to look at photographic reproductions, but never were they to copy directly from any of those. “The idea was to feed the imagination with visual images of the human form” and to draw later from this “storage of visual impressions accumulated partly in memory but mostly in subconsciousness.”8 According to Bloom, Zimmerman “dis-inhibited the student so that he could follow a succession of images. It was a technique of working which made it possible to follow the movements of the imagination.”9 The main source of inspiration was not the real world but the art of the past. Should the students wish to draw hair, they would study the hair in Botticelli’s paintings; to draw a knee, they would turn to Michelangelo.

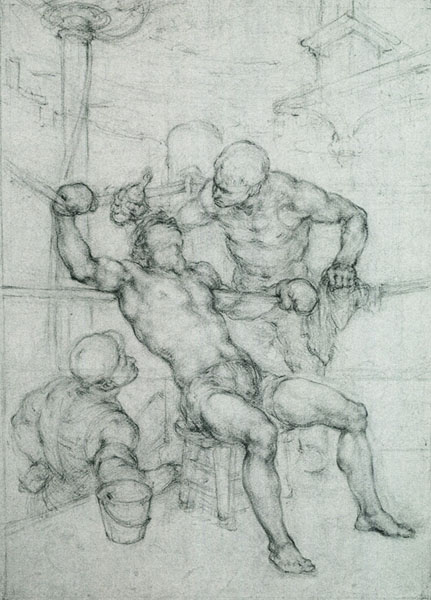

A devoted teacher, Zimmerman gave his instruction free of charge to his most talented students, Bloom and Jack Levine. The drawings Bloom made in Zimmerman’s class at the age of fourteen and fifteen show a remarkable mastery of the human anatomy. Their swirling forms and linear style reflect Bloom’s early admiration for William Blake, whose mythical and visionary world also inspired some of their subjects: Prometheus, The Opium Smoker’s Dream, Virtue Victorious over Brutality, and Man Breaking Bonds on Wheel (fig. 20).10 In a more realist vein, Bloom drew scenes from boxing and wrestling games (fig. 1, 3), which have their source not only in Blake, Rubens, and Michelangelo, but also in the musculature of Bloom’s eldest brothers — two bodybuilders whom the physically frail artist observed with envy. “Jack [Levine] and I had very different interests,” Bloom recalled, “Jack was always interested in heads, I was interested in muscles.”11

Zimmerman’s experimental method and the exceptional quality of his students’ work attracted the attention of Denman Waldo Ross, an artist, collector, and Harvard professor, who offered to subsidize Bloom and Levine and teach them painting. He rented a studio for them and offered the young boys a stipend of $12 a week. Once a week, on different days, Bloom and Levine went to Ross’s house to receive instruction. Ross had written several books of art theory, in which he elaborated a system of rules of design and color. Persuaded “that it is perfectly possible to make of the painter’s palette an instrument of precision,” he established scales of values and colors and devised methods to arrange the pigments on the palette according to a theory of tone relations.12 Using music as a model, he organized colors in scales from light to dark and cool to warm. Recalling his training with Ross, Levine pointed to the limitation of Ross’s method: Once the palette was organized like a keyboard, there was no rule on how to place the paint on the canvas. Ross, Levine said, “didn’t know anything about layering, glazing, etc.: He was an impressionist painter.”13 Ross’s collection and his vast knowledge of art history were perhaps more influential on Bloom and Levine than his painting instruction. An expert in Oriental art, Ross owned over 10,000 objects, which he eventually gave to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. 14

THE FISH, THE SYNAGOGUE, AND THE CHRISTMAS TREE

Ross’s knowledge of art history, however, did not extend beyond Impressionism, and little modern art was available in conservative Boston until the creation of the Boston Museum of Modern Art in 1936.15 In the early 1930s, Bloom traveled to New York with Zimmerman to visit the newly opened Museum of Modern Art there and view examples of European modernism in private galleries. He was particularly impressed by Soutine and Rouault. “It was a clarifying experience,” he said later, “and I began to imitate Rouault to Zimmermann’s chagrin and Ross’s dismay. Ross couldn’t stand Rouault or even Cezanne.”16 Although Rouault’s popularity declined in the second half of the century, he was highly regarded as a modernist in the 1930s and 1940s. Pierre Matisse exhibited him regularly in his New York gallery, and by 1939 the catalogue of the exhibition Art in Our Time at The Museum of Modern Art, which included several Rouaults, described him as “the greatest of the artists called ‘Expressionist.’” Rouault’s religious mysticism and his reliance on color and the sensuous quality of paint to express it on canvas appealed to Bloom, who was searching for a pictorial form that would convey the intensity of his own spiritual preoccupations.

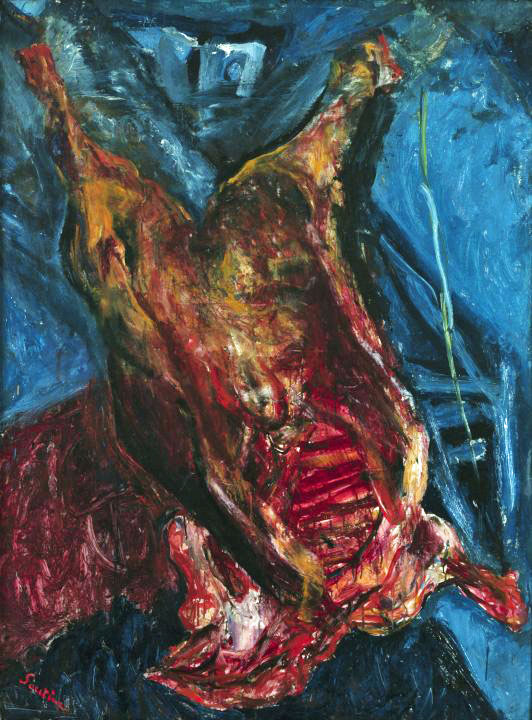

Bloom felt even closer Soutine, who had the same Eastern European origins did, and whose paintings struck him from the beginning as “very Yiddish.”17 When shown in the United State: Soutine’s paintings had been criticized as “the creations disintegrating mind,” but interest in his work rose in 1930s, culminating with four solo exhibitions in New York galleries in 1936 and 1937.18 Soutine’s commitment to painting from direct observation (he was known for throwing fresh blood on carcasses to revive their colors while working on them) was at odds with Bloom’s emphasis on the imagination. But as in Rouault, Bloom found in Soutine style that could convey emotion and a sense of the tragic, a modern equivalent to the painterliness of Titian and Rembrandt. In the 1930s, Bloom painted several circus scenes directly influenced by Rouault, including the latter’s trademark of a heavy black outline. Although this black contour is still present in The Fish of circa 1936 (fig. 5), its subject and handling are closer to Soutine. The focus on the dead animal, the intense red of its entrails, and the bold, swirling brushwork recall Soutine’s own depictions of dead fish, plucked fowl, and sides of beef (fig. 4). Under the influence of Rouault and Soutine, a heavy dose of realism entered Bloom’s art, not as an end but as a means to express his ideas on life and, especially, death — a theme that would become central to his art in the following decade.

In the last years of the 1930s, Bloom’s involvement in mystical and spiritual matters increased. Prompted by the reading of Helena P. Blavatsky’s occult treatise The Secret Doctrine, and seduced by its mixture of esotericism and Eastern philosophy, he attended lectures sponsored by the Theosophical Society, of which Blavatsky had been one of the founders in 1875. In search of a solution to his growing anxieties and profoundly disturbed by the suicide of his close friend, the artist Elizabeth Chase, in the fall of 1939, Bloom looked in many directions for a meaning to life. He joined the Order of the Portal, an offshoot of the Rosicrucian Order, visited the Spiritualist Church and the Psychical Research Society, and attended meetings at the Vedanta center. It is in the midst of such a spiritual quest that he produced his first ambitious painting, The Synagogue (fig. 23), a work that attracted much attention at the Americans 1942 exhibition and was purchased soon after by The Museum of Modern Art. Looking into his own background for a subject that would express a transcendental experience, Bloom remembered the feeling of ecstasy aroused in him by the cantoral music he heard at the synagogue. To give this feeling visual expression, he used formal distortions and an animated paint handling that suggest the transport of the singers. The heads turned ninety degrees upward and the swinging of the chandeliers under the ceiling materialize the sound of the music filling the space of the synagogue. Such an emphasis on physical expression corresponds to the theatricality and emotionalism that characterizes Eastern European synagogal music. This musical tradition, represented for instance by the cantor Pierre Pinchik whom Bloom admired, is well known for its moving and pathetic accents and for the wide range of emotions the cantor expresses in order to seduce –almost hypnotize–the listener and renew his faith.19 In the Hassidic tradition, in which the chant plays a major role, the cantor accompanies the melody with movements of his torso, his arms, and his entire body to the point that he appears to be “in a real state of trance.”20 Bloom’s comment about Soutine’s paintings being “very Yiddish” resonates with this music’s particular emotional appeal. He immediately felt that these works were “in line with Hebrew music,” that both expressed the same “suffering.”21 A Jewish feeling in art,” Bloom said, is often reflected through a sense of nervous energy or exuberance -– pathos — angst …it is epitomized by the music of the synagogue …it is weeping from the heart.” 22

The ecstatic experience suggested in The Synagogue doesn’t come only from the music but also from the intensity of the light, represented by the chandeliers, the menorah candles, and the wall candelabras. Bloom developed this theme in a group of pictures of Christmas trees and chandeliers painted from about 1939 to 1945 (fig. 2, 25, 26, 30). In all of them the illuminated object dominates the picture surface to such an extent that light itself becomes the subject of the painting. The glimmering effect of the refraction of light on the crystal pendants of the chandeliers is rendered by short strokes of rich color applied in multiple layers of fluid paint, in a technique reminiscent of Bonnard. Despite the Christian connotation of the tree, the flame-like brush strokes and the red and yellow palette evoke the imagery of the Burning Bush, a major symbol of Jewish mysticism. Abstracted from their surrounding, the trees and chandeliers lose their material presence and acquire a visionary quality. Their insistent symmetry, and, especially in the case of the chandeliers, the two-dimensionality of their rug-like patterns, remove these objects from the domain of empirical observation to transform them into symbolic images of light as a spiritual phenomenon.

EXQUISITE CORPSES

Even a blind person can see that you are a corpse. Unbutton your coat, and you will see that you are walking about in a shroud.

Isaac Singer, “In the World of Chaos” 23

Well, of course, we are meat, we are potential carcasses…. And, of course, one has got to remember as a painter that there is this great beauty of the colour of meat.

Francis Bacon 24

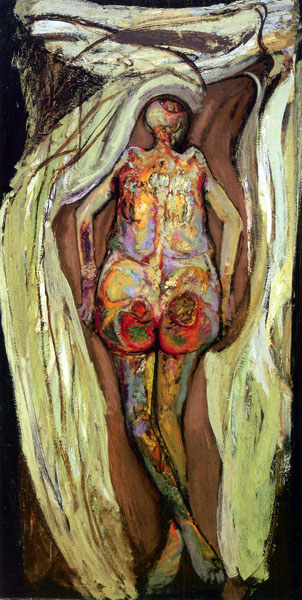

In the mid-1940s, Bloom painted three extraordinary pictures of corpses — two female, front and back, and one male (fig. 6, 28, 29). Upright and almost life-size, the naked corpses stand in front of us devoid of anecdotal context, apart from the suggestion of the morgue in the shrouds that surround them. The sagging flesh of their decaying bodies is depicted in the most unlikely shimmering red, green, and yellow. In the same years, Bloom also painted A Leg (fig. 8), a brightly colored, gangrenous limb isolated on a table against a bare background. The inspiration for these decomposing cadavers and body parts came from a visit to Boston’s Kenmore Hospital in 1943 with artist David Aronson, who, having obtained a pass to go to the morgue and do sketches for a painting of the Resurrection, invited Bloom to come along.25 “On the one hand it was harrowing,” Bloom recalled of his viewing of a dead body, “on the other it was beautiful–iridescent and pearly. It opened up avenues for feelings not yet gelled. It had a liberating effect. I felt something inside that I could express through color. As a subject it could synthesize things for me. The paradox of the harrowing and the beautiful could be brought into unity.”26

At the morgue, Bloom observed firsthand the transformation of the body after death, especially the changing color of the flesh. His paintings evoke the descriptions of medical experts familiar with the colors that mark the successive phases of putrefaction, “the red, green, and black palette of bacterial growth that creeps across the body in the days and weeks after death.”27

To complete his observation, Bloom immersed himself in old medical treatises that feature brightly colored depictions of wounds, lesions, and other ulcers for the education of the medical student, such as the multi-volume Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion (1861–65), with its color lithographs of bullet wounds, lacerations by shell fragments, gunshot fractures, and numerous forms of gangrene (fig.7). 28

The latter especially offer a vivid palette of red, green, and black, which found its way into Bloom’s Leg. The verticality of Bloom’s corpses, their systematic front and back presentation, and the clinical display of the amputated leg also refer to textbook images.

The subject of death preoccupied Bloom early on. In the mid-l930s, he painted on a narrow horizontal canvas a skeleton, derived from Hans Holbein’s The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb.29 In the traditional Western representation of the male corpse, dominated by images of Christ’s crucifixion, deposition, and entombment, Holbein’s painting stands out for its striking immediacy. The viewer is confronted at eye level with a bold close-up of a realistically rendered, stiff-dead body lying inside a tomb. No sign of transcendence or divinity in this unsettling depiction, which prompted Dostoyevsky to exclaim, through the character of Prince Myshkin who comes upon this painting in a scene in The Idiot: “Why, some people may lose their faith by looking at that picture!”30 Holbein emphasized the humanity of Christ by exposing the bare fact of death in such a crude image. Yet, in doing so, he underscored by contrast the miracle of the Resurrection. For Bloom also, who believes in reincarnation, the reality of the death of the flesh brings home the life of the spirit, a theme he explored in his corpse paintings.

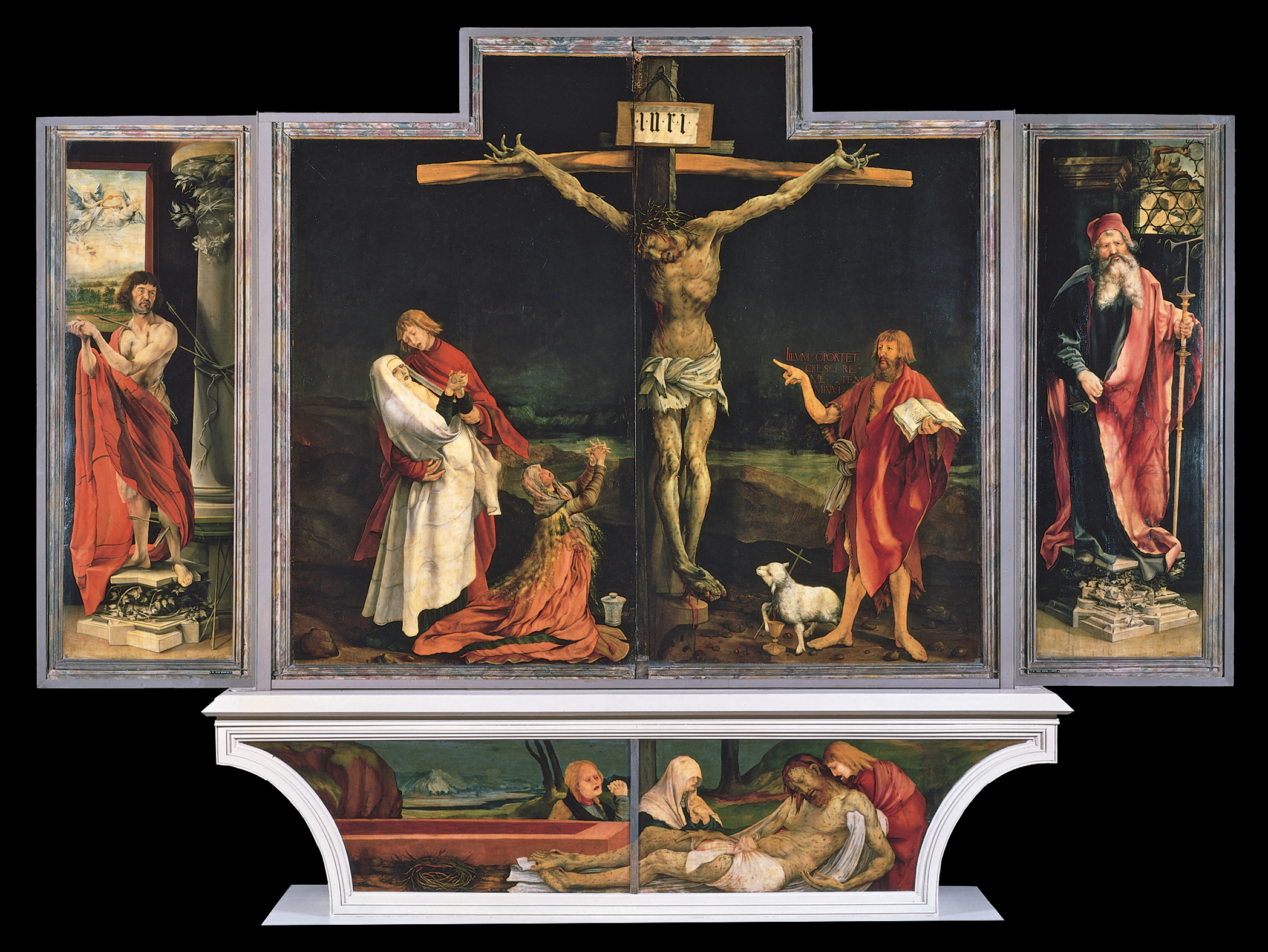

Despite its realism, Holbein’s Christ, like most of the dead Christs from the Renaissance on, shows little of the wounds and lesions inflicted by the torture of the Passion. One must turn to another masterpiece of early German Renaissance, the Isenheim Altarpiece, to find images comparable to Bloom’s in the depiction of a suffering body (fig. 9). In Grunewald’s polyptich, Christ’s body, lacerated by the flagellation and the crown of thorns, already suggests the putrefaction of the flesh, while on a side panel representing the Temptation of St Anthony, another figure displays a skin covered with sores. The famous altarpiece, which was rediscovered in the middle of the nineteenth century and which had already been a subject of fascination for the symbolists and the German expressionists, was familiar to Bloom, who studied it in reproduction.31 The altar was all the more relevant as a source for Bloom that it was initially associated with the curing of illnesses, especially the so-called St Anthony’s Fire, the symptoms of which included gangrene and severe muscle cramps-hence the skin disease and distorted hands of the painting.32

Bloom’s corpses mark a culminating moment in the rep- representation of the body in modern art, a representation that began its drastic transformation at the end of the nineteen century. At that time, the invention of radiography, the publication of photographs of medically- and mentally-ill patients, the collections of wax models and casts of deformities assembled by doctors, and the development of anthropology, with its study of human physiognomy, heralded a new era in the depiction of the human body.

“This material,” Jean Clair wrote: “would be to modern art what the re-opened excavations of Rome had been to the Renaissance: an immense repertory or stockroom in which to find a contrario, new models the contemporary world.”33 The realists-Courbet, Manet, Degas-had already abandon the classical canon of beauty. With the symbolists, and even more so the cubists, expressionists, and futurists, the body in art was subjected to all sorts of transformations,deformations, and fragmentations. The frontier between the inside and the outside of the body opened up as the inner body was explored both physically with X-rays an, mentally with psychoanalysis. Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avigno and Oskar Kokoschka’s early portraits are major examples of this disintegration of the body in the first decades of the twentieth century. The atrocities of World War I led to further representations of distorted bodies, as in Otto Dix’s gruesome depictions of dead and wounded soldiers. In the early 1940s the war led artists to question again the possibility of painting the figure. “A time came,” Mark Rothko said of these years, “when none of us could use the figure without mutilating it.” 34 The last figurative paintings Rothko produced before developing his abstract style were crucifixion scenes inspired by Grunewald and depicting fragmented bodies (fig. 10).

Bloom’s corpses have often been linked to the war and the Holocaust.35 The artist, however, denies having painted them as a specific response to contemporary events. His strict Orthodox background instilled in him a deep concern with the long history of the persecutions of the Jews. As Sydney Freedberg expressed it in a 1949 review of Bloom’s paintings: “The decaying corpses of the medical school became a visual symbol in which there converged a major concern of Bloom’s private psyche and a general comment on the situation of the world at war.”36 Moreover, Bloom’s paintings differ from the works of artists, such as Rico Lebrun, who were inspired by the atrocities of Buchenwald or Auschwitz in that Bloom’s purpose was not to express horrors, but to celebrate life and convey a positive message about humanity. “Life is not just what we experience on earth,” he said, “you don’t just die and rot away. That would tell us that life is trivial, and that wouldn’t make sense.”37 In contrast to the conception of the “perfect” body promoted by the Nazis in their National Socialist art, Bloom proposed the decaying corpse as a symbol of immortality. “In his paintings,” Freedberg continued, “the luminescent markings of decay upon the corpse are symptoms of the continuation of organic processes; the very activity of putrescence is a kind of victory over death.” For those, like Bloom, who believe in reincarnation, death is part of a larger vision of life; it is but one phase of the universal cycle. “The paintings are emblems of metamorphosis,” Bloom said, “as the living organisms which inhabit the body in death transform it into life in another form.” 38 Therefore, death should be seen as a peaceful process. Describing the last of the three corpses (fig. 6), Bloom evoked the serenity of this cycle of human decay and rebirth. “The Female Corpse, Back View I see as being more subdued, opalescent, nocturnal than the other corpses. It has some of the quiet coldness of bodies returning to earth.”39

Bloom can look at an actual corpse with none of the shudder that would shake most of us. Fascinated by science, especially medicine, he observed the corpses at the morgue with the detachment of a surgeon. (A friend described him watching an autopsy, concentrating on figuring out which red pigment could match the deep hue of the blood dripping in the pan.40) Confronted with the reactions of disgust expressed by some viewers in front of his paintings, Bloom candidly replied: “I really thought people would be delighted. It seems to me that if you have any conviction of immortality you can look at such a subject as objectively as at anything else. The body is very beautiful and its insides are just as beautiful as the outside.”41 In Corpse of Man (fig. 29), the emphasis on the sexual organs prominently exposed in the center of the painting points to the regenerative role of death. The picture associates sex and death as the two natural forces essential to the survival of humanity, a theme Bloom will take up again in later paintings such as The Facts of Life (fig. 58). In this context, one can also speculate on the meaning of the skin diseases that affect Bloom’s corpses, since such afflictions are commonly related to syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases. (In his recent study of the Victorian Age, Peter Gay tells the story of the playwright Arthur Schnitzler, whose father, upon discovering that his sixteen-year-old son was having a lively sex life, forced him to read a treatise on syphilis and skin diseases, accompanied with gruesome illustrations. 42)

More generally, Bloom himself commented on the corpses as metaphors for human moral corruption. The bodies are emblems in which the process of decay symbolizes the corruption of society and of the human spirit.” 43 Yet,in representing this process of decomposition with the most seductive colors, Bloom exposed the ambiguity between attraction and repulsion, thereby giving a visual expression to the “paradox of the harrowing and the beautiful” that he felt when first visiting the morgue.

HYMAN BLOOM, AN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST?

In one rare instance, The Harpies of 1947 (fig. 31), Bloom set the theme of the corpse within a mythological context. A barely recognizable body–the hand at the bottom is the most legible part–is being torn apart by winged black creatures, the Harpies, ravenous monsters of Greek and Roman mythology known for their destructive behavior. In subject and style this painting is close to the Abstract Expressionists’ contemporary works. Its congested space and turbulent brush strokes recall Pollock’s 1943 myth paintings such as Pasiphae (fig. 11), in which the mythological figure is called upon to express the power of the sexual drive and the bestiality of man. The hand on the margin of The Harpies also brings to mind Pollock’s own hands on the edge of the later Number IA, 1948, a human presence emerging from the web of lines and stains covering the canvas.44 It is not surprising that in her 1950 article “Hyman Bloom Paints a Picture,” Elaine de Kooning singled out The Harpies for analysis. Her description could apply as well to a painting by Pollock or Willem de Kooning: “The composition progressing toward total abstraction, seems to devour the subject, and the whole impact is carried in the boiling action of the pigment.”45

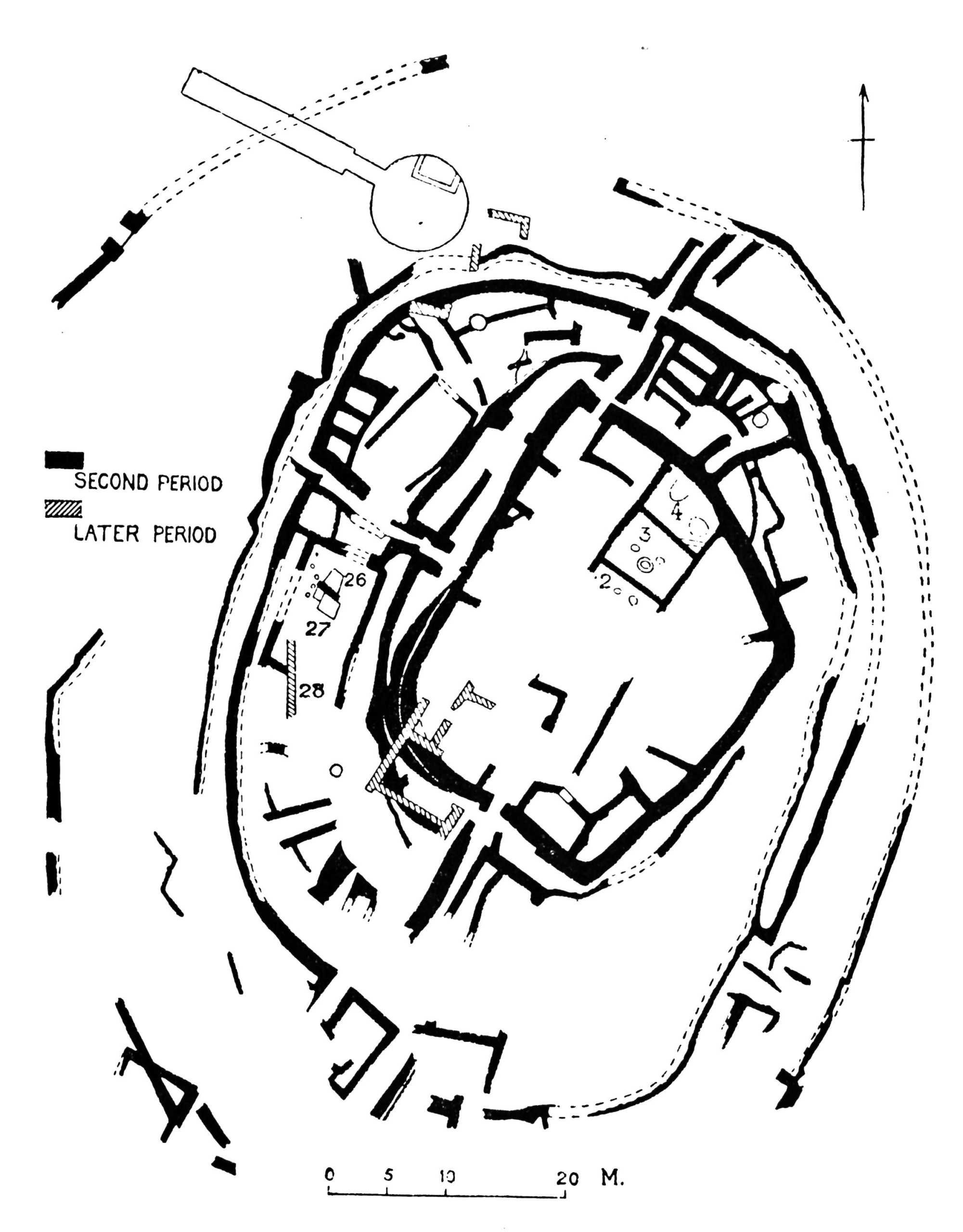

Bloom flirted with abstraction in a few other works of the late 1940s, which can be loosely called his “archeological” paintings, such as Archaeological Treasure and Treasure Map (fig. 32 and 13). In them, Bloom, like Rothko, Pollock, and William Baziotes at the same time, explored the mysteries of origin. No longer probing the insides of the human body but the insides of the earth, he exposed the beauty of these excavations with the same bright palette and sensuous brushwork he used for the corpses. Seen from above and close-up, these openings into the earth’s body reveal the same richness as the corpses’ open wounds. The comparison with the human body is reinforced in Archaeological Treasure by the resemblance of the vertical element on the right of the painting to a human spine and by the flesh color of the circular form that contains the treasure, comparable to a womb. The circular black pattern of Treasure Map is based on a map of the ancient city of Dimini that Bloom happened to see in a magazine at the time (fig. 12).46 Replying to a critic who speculated on the meaning of such a reference, Bloom clarified: “I came across the little map when I was working on the picture and made use of it. It could have been a map of anyplace…. the ‘programme’ of the picture can be put simply. There is a treasure buried in the earth. (The Earth symbolically is Adam, our body, the sense nature.) What is buried (the soul-transcendental nature) shines through and by the nostalgia it evokes incites us to its complete discovery. The uncovering of this treasure being the fulfillment of our wishes. The ‘map’ is form of something unseen as yet–a ‘promise.’” Bloom concluded with a concession to the critic: “The picture is a symbol of course, and you are entitled to whatever interpretation wish to give it.”47

The Abstract Expressionists insisted on the spiritual content of their paintings, an aspect that is also at the core of Bloom’s art. Like his corpses, Blooms’s archeological paintings reflect his metaphysical beliefs, notably the theory, central to theosophy of the “inner life” of everything. According Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine, “Everything in the Universe…is conscious: i.e., endowed with a consciousness of its own kind and on its own plane of perception. We men must remember that because we do not perceive any signs–which we can recognize–of consciousness, say, in stones, we have no right to say that no consciousness exists there.” 48 Bloom’s archeological paintings-one of them is significantly entitled The Stone–evokes this life of the spirit in all matter.49 Bloom’s slow, labor-intensive painting method, which involved working and reworking over lengthy periods of time, mirrors the slow process of excavation of the treasures from the earth. “In so exactly attuning the symbol with his means, Bloom’s minerals are also those of the chemistry of paint,” Thomas B. Hess wrote about The Stone, which he included in his 1951 landmark survey, Abstract Painting: Background and American Phase 50 His assessment of Bloom’s abstraction clearly related him to the Abstract Expressionists: “In Hyman Bloom America has another artist who fuses the abstract and Expressionist traditions, and who has achieved this difficult act within the limits of his personal metaphor-never forgetting that life and death-the body that relaxes from worship and the one that rests on the dissecting table-are one.”51

In his recollections of the 1940s in Boston, the painter Bernard Chaet reported: “Willem de Kooning … made it very clear to me in a conversation in 1954 that he and Jackson Pollock considered Bloom, whom they had discovered in Americans 1942, ‘the first Abstract Expressionist artist in America.” 52

As for Bloom himself, he thought abstraction was “a blind alley” and he treated this phase of his career as a brief experiment: “I tried Abstract Expressionism and came as close to it as I wanted to. But I thought that it was mostly emotional catharsis with no intellectual basis. It had no emotional control.” 53

CORPSES AGAIN, INSIDES OUT

I know two sorts of painters: those who believe and those who do not believe in skin.

Andre Breton54

Bloom carried his exploration of the human corpse further in the late 1940s and early 1950s with paintings of autopsies and dissections. “My concern,” he explained, “was the complexity and color beauty of the internal works, the curiosity, the wonder, and the feeling of transgressing boundaries which such curiosity evokes.”55 Composed differently than the earlier corpses, these paintings show the dead bodies propped on a table, their entrails exposed (fig. 36, 39). In several of them the hands of the surgeon performing the autopsy hover over the open cadavers. The ironically entitled The Hull (fig. 36) includes a more violent note: one of the hands still holds the knife used to cut the rib cage out of the chest. Related to these paintings are several large-size drawings, superb sanguines in the Italian mannerist tradition (fig. 19, 38 and cat. 44). In 1949, Bloom had been hired to teach at Wellesley College on the recommendation of Sydney Freedberg. Was it the influence of this scholar of sixteenth-century Italian art that turned Bloom toward this period? Adopting the erotic pose of a Mannerist reclining Venus, Female Cadaver (fig. 19) offers to the viewer the insides of her body. With their elongated forms, acerbic colors, and long sweeping brush strokes, Bloom’s paintings of the early 1950s are closer to Pontormo or Parmigianino than to Soutine.

To be sure, dissection has a long tradition in the history of painting, from Rembrandt to Thomas Eakins to Kiki Smith. While the Anatomy Lessons of the past centuries focused on the portraits of the surgeon and its attentive audience, as in Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, Bloom zooms in on the center of the operation, focusing on the open torso and viscera.56 But like Rembrandt or Eakins, Bloom preserves the sense of drama that was associated with such events, when dissections were staged performances taking place in specially designed theaters.57 In his Anatomist (fig. 39), the drama is conveyed by play of hands: that of the corpse, thrown back in a theatrical gesture reminiscent of Christ’s raised arm in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, and the disembodied hands the surgeon springing from the right margin of the canvas reach inside the open flesh.

Bloom is not the only artist of the second half of the twentieth century to have explored the aesthetics of the insides of the body. In 1960, an exhibition at UCLA paired him with Francis Bacon, another artist fascinated by slaugherhouses and butcher shops. 58 Bacon specifically described his interest in the inside of the mouth, in a manner that recalls Bloom’s approach. Bacon remembered being obsessed with a book “which had beautiful hand-coloured plates of diseases of the mouth, beautiful plates of the mouth open and of the examination of the inside of the mouth.” I like,’ he added, “the glitter and colour that comes from the mouth, and I’ve always hoped in a sense to be able to paint the mouth like Monet painted a sunset.” 59

More recently, Kiki Smith’s mixture of references to medicine and religion also echoed Bloom’s interests. Smith immersed herself in old medicine books, Renaissance pictures of circulatory systems, and books about dissection. She even studied to be an emergency medical technician. Like Bloom, she was drawn to Northern European art of the late Gothic period and admired Grunewald for his use of the physicality of the body for expressive purposes.” 60 In her sculpture, Smith has been credited with revalidating the body as a subject matter, but her interest goes beyond the naturalist representation. “In working with the body,” she said, “I feel I’m actually making physical manifestations of psychic and spiritual dilemma.” 61 In a striking combination of the physical and the spiritual, Smith has depicted the Virgin Mary as a flayed body, shining with the inlaid silver of her veins (fig.14). Fascinated by Catholicism’s stress on physicality, she conveyed in such an image the idea that it is from being incarnated “insistently and defiantly in the flesh” that the female deity derives her power.62

CHALLENGING PERCEPTION: THE ARTIST AS MEDIUM

I now suddenly understood how, to a painter — had it not happened to Rembrandt and many others? — ugliness could appear as the true reservoir of beauty, better than any treasure cask, a jagged mountain with all the inner gold of beauty gleaming from the wrinkles, glances, features.

Walter Benjamin “Hashish in Marseilles”63

In 1954, after reading The Doors of Perception, Aldous Huxley’s essay on the hallucinatory effects of mescaline, Bloom volunteered for an experiment on LSD’s influence on creative activity. His reactions and observations, recorded by the psychiatrists who conducted the experiment, concurred with Huxley’s. Mostly, Bloom noted the greater intensity of every color “as if I noticed them for the first time.”64 According to Huxley, colors take precedence over spatial relationships in the perception altered by drugs: “Colors are more important, better worth attending to, than masses, positions and dimensions…. Mescalin raises all colors to a higher power and makes the percipient aware of innumerable fine shades of difference, to which, at ordinary times, he is completely blind.” Describing the specific environment in which he took the drug, Huxley continued: “Where the shadows fell on the canvas upholstery, stripes of a deep but glowing indigo alternated with stripes of an incandescence so intensely bright that it was hard to believe that they could be made of anything but blue fire”65 To Bloom, who had been striving to reproduce the brightness of light itself in his pictures of chandeliers and Christmas trees, the experiment was “an eye-opener.”66

But it was not only the physical effects that attracted Bloom to the experiment. “I was interested in the philosophic aspects of LSD as a religious experience,” he explained.67 In The Doors of Perception, Huxley likened drug taking to the experience of the mystics, psychics, and mediums, and promoted it as a way to fulfill the religious need for transcendence. To Bloom, the LSD, like his participation in seances, was an attempt to find answers to his metaphysical questions by expanding his perception. He was hoping to witness some of the phenomena described by visionaries and mystics, such as William Blake. But, just as such visions are ineffable, they cannot, Bloom admits, easily be represented. A common characteristic of ecstatic confessions is that they abound in metaphors of fire and blaze.68 In this regard, Bloom’s chandeliers and Christmas trees were his first effort at giving ecstatic visions a pictorial form.

In the early 1950s, he tackled the metaphysical directly in several paintings and drawings of occult subjects. The earliest ones, Apparition of Danger (fig. 34) and The Medium (fig. 35), both of 1951, use color to express the transcendent. In both, the central figure–the medium–is holding the hand of other unseen figures, presumably participants in the seance. Bright red and yellow forms hovering above him suggest apparitions emerging from the dark background, as light coming out of the shadow. In The Medium, one of the apparitions is a Native American whose face painting and feathered headdress are symbols of divine forces within natural forms.

Because Bloom never observed psychic phenomena such as objects in levitation or people in trance-during the seances in which he participated, he relied on published descriptions. In his Seance paintings (fig. 41, 43, 44), the white forms floating in the air and surrounding some of the figures represent the ectoplasm, the luminous substance that appears to emanate from the medium’s body during a trance. In Seance III, for instance, the vision takes the form of a wing. The strained gestures of the hands in the foreground of Materializing Medium, with the fingers convulsively crossed or pulled backward, have their roots in medical descriptions of patients in a state of hysteria. They also, however, refer to art historical sources: the expressive hands in Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece or in Kokoschka’s portraits, in which the hands convey the sitters’ personalities as much as their faces do.69

Iconographically, Bloom’s Seance paintings hark back to the Symbolist era, when painters and poets were deeply involved in spiritualism as a reaction against the development of materialism and rationalist philosophy. The mask-like faces of the figures in Bloom’s paintings recall the carnivalesque and hallucinatory imagery of Odilon Redon and, especially, James Ensor, whose masked characters are intermediaries between the living and the dead.

Bloom’s ties to Symbolism are even more explicit in a group of drawings of 1965 and 1966 directly inspired from theosophy (fig. 53, 54). Generically entitled On the Astral Plane, the drawings refer to the spiritual journey of humanity as described in the teachings of the Theosophical Society. The astral plane is one of the stages in the general evolution of consciousness to which each individual contributes. It is the level of emotions, desires, and passions. All of Bloom’s drawings are devoted to the lower astral plane, which he describes as “an area of dreams, nightmare, unhappy emotional states, an indivisible world of suffering, in opposition to the higher plane, which is a paradisiacal world.” Asked why he only drew the lower plane, Bloom replied: “You draw your experience.”70 In his depiction of the lower plane reigns Beelzebub and other demonic creatures, insect-like monsters crawling over human heads in a chilling vision, made even more frightening by the dramatic contrasts of light and dark.

“Painting is passing from physical bodies to ether and astral ones,” the Russian philosopher Nikolai Berdiaev stated in 1916, in one of the clearest formulations of the connection between art and mysticism at the beginning of the twentieth century.71 Interest in the occult and the metaphysical played a central role in the culture of Eastern Europe and Russia from which Bloom came. As John E. Bowlt demonstrated, the esoteric culture predominant in Russian society at the turn of the century was fodder on which the avant-garde nourished itself and developed in the following decades.72 Well versed in philosophy and a reader of P. D. Ouspensky and H. P. Blavatsky, Bloom shared with the Symbolists and the early abstract painters a conception of art as a religious and spiritual quest. He admired Kandinsky’s early paintings and was familiar with the theories that informed Kandinsky’s 1910 treatise Of the Spiritual in Art. Although Bloom rejected abstraction, considering it a dead end, he agreed with many of the precepts developed Kandinsky, among which one of the most important was the intimate relation between painting and music.

THE COLOR OF MUSIC

Bloom’s passion for Middle Eastern and South Asian music has been one of his main sources of spiritual strength throughout his life. He plays a number of musical instruments–the Indian veena, the sitar, and the Turkish saz, among others—and has been an avid collector of world music records since the 1930s. His range of interest is wide, including Indian, Armenian, and Arabic music, ancient Greek songs, Flamenco, Tibetan melodies, and more. Bloom loves traditional music because it expresses basic emotions, “something old and primal, a majestic feeling of timelessness,” which he would like his paintings to elicit as well.73 “The music arouses feelings I would like to communicate in painting-an aesthetic experience through one sense expressed through another”74

Bloom’s interest in music began with the Jewish cantoral music he heard in synagogue during his childhood. We saw earlier how this musical form found a visual expression in the painting The Synagogue (fig. 23). Like traditional Jewish music, Indian music, which Bloom discovered through an album of Uday Shankar’s orchestra in the mid-1930s, exerted a special hold on him for its combination of spirituality and emotion. Few recordings of Indian music were available in the U.S. in the 1930s and Bloom began ordering them from abroad. Later on, around 1960, he co-founded the Pan Orient Arts Foundation, devoted to the collection and promotion of Oriental music, especially South Indian classical music, also called carnatic music. The main force of the Foundation-and its financial backer-was James A. Rubin, an enthusiast of Indian music who was befriended by the singer M.S. Subbulakshmi. In the 1960s, Rubin traveled regularly to South India to record concerts and performances of popular and classical music. The Foundation also arranged tours of famous Indian musicians and singers across the United States. As a trustee, Bloom had access to the hundreds of recordings gathered by the Foundation, which eventually formed the most comprehensive collection of carnatic music recordings in the world.75

Bloom’s art relates to the aesthetic of Indian music in several ways. Indian music is based on the concept of raga, which means “color” in Sanskrit. At once a scale and a set of rules to use it, each raga corresponds to a particular feeling and is associated to a season and a moment of the day. It is supposed to arouse a wide range of emotions-love, anger, fear, surprise, pathos, courage, serenity-at different levels of intensity, all leading eventually to pure aesthetic pleasure.76 Likewise, Bloom relies primarily on the emotional value of color to move the viewer. The wide range of hues and tones he explores in his paintings corresponds to the subtlety of tones and microtones that characterizes Oriental music and distinguishes it from Western music, which relies more on instrumentation and orchestration. Brian Silver, a sitar player and scholar of North Indian music and languages and a close friend of Bloom’s, talked about the musical color of the ornamentation typical of Indian music and compared it to Bloom’s painting, which, he said, shares the same “transcendent luminosity.” 77

In a more general manner, Bloom’s conception of art as an investigation of the self bears resemblance to the philosophy behind the ritualistic performance of music in India. As Ananda K. Coomaraswamy described it, “The [Indian] song is a ritual, a sacred ceremony, an ordeal which is designed to set at rest that wheel of the imagination and the senses which alone hinder us from contact with reality.”78 Indian music has a magical effect; it induces a state of contemplation and ecstasy that gives the listener an intimation of a timeless and spaceless world.

Bloom counted many musicians and composers among his friends, including the Armenian-American Alan Hovhaness (1911-2000), whose music was inspired by mystic philosophy and religious and ethnic music, from Armenian folk songs to Japanese religious music. In 1948, the avantgarde magazine The Tiger’s Eye ran an article on Hovhaness, one of “The Three Magi of Contemporary Music,” which described his conception of the melody indebted to Eastern music: “According to the composer, the melodic line follows a single continuously spiraling movement. Such a movement is submitted to many variations and-without undergoing the traditional harmonic and modulating elaboration-it grows and enriches itself with sound and melodic contrasts and also with modal mutations…. It is supposed to exert some kind of hypnotic power over the listener.”79 Such a spiraling movement characterizes the composition of Bloom’s Seance pictures and, even more so, his drawings and paintings of fish, begun in the mid-1950s (fig. 21, 47, 56, 61), in which swirling fish heads and skeletons create a dynamic, continuous circular movement throughout the surface, a visual image of the uninterrupted melody of Indian music.

THE LAWS OF NATURE

I see expression in the whole of nature, for instance in trees, and, as it were, a soul.

Vincent Van Gogh 80

Beginning in the late 1950s and for about ten years, Bloom set painting aside and concentrated on drawing. “I wanted to develop a feeling for light and dark,” he said.81 Some drawings explored the artist’s familiar themes — corpses, Jews with the Torah, and seances — while others introduced new subjects based on nature, inspired by Bloom’s trips to Lubec. Bloom first went to this fishing village on the coast of Maine in 1954 with his new wife, Nina Bohlen, an artist and one of his former students at Harvard. The couple returned there regularly the following summers. On the beach of Lubec, Bloom found dead fish, which attracted him for the interesting shapes of their skeletons, and he began drawing them. Far removed from the bloody fish lying on a table in his early treatment of the subject (fig. 5), the fish skeletons became the basis for densely linear compositions, in which many fish swirl around in an elaborate design (fig. 21, 47). Beyond the formal aspect, the dead fish acquired for Bloom a symbolic meaning. In these visions of life and death at the bottom of the ocean, where the big fish eat the small ones, nature became a metaphor for the competitive world. “Eating, pursuit, and dying,” Bloom explained. “It’s a euphemism for free enterprise, a predatory competition. Life is a contest.”82

Most spectacular among the works Bloom produced during this decade are his monumental charcoal drawings of trees, inspired by the woods near Lubec (fig. 15, 50-52). Equipped with a camera and a tripod, Bloom took photographs of the dense network of trees and used them as a source for his drawings (see photo p. 82). He did not, however, copy the photographs. Combining reality and imagination, these large-size close-ups of entangled branches, twisted roots and gnarled tree trunks create a fantastic world in which nature becomes alive on the paper. Their strong chiaroscuro heightens the sense of drama, as in the prints and drawings of Redon and Rodolphe Bresdin, which Bloom admired and collected. “I thought by reducing the variables I could get to fundamental issues. The Sung painters, after all, have a complete aesthetic in black and white, and I had hoped by imposing such limits I might be able to give greater strength to the whole composition. Also I wanted to explore charcoal tone as Redon had done, and pursue ideas I had developed from studying the drawings and prints of Altdorfer and Bresdin.”83

Uninhabited and uninviting, Bloom’s forest scenes show no path or trail. In most of them, the absence of sky creates a feeling of claustrophobia, while the dense black of the background, as in Landscape #3 (fig. 50), suggests the frightening vision of the forest at night. Bloom’s landscapes belong to the romantic tradition that sees in natural phenomena the mirror of the human condition. In this empathy with nature, a tree can become, in the words of Robert Rosenblum, “the protagonist of some drama more human than botanical, and the conveyor of sensations more emotional than physical.84 The German romantics especially endowed their landscapes with such spiritual meaning. Bloom’s Landscape #2 (fig. 15), in which a single dead tree dominates the composition, recalls Caspar David Friedrich’s Solitary Tree of 1822, a highly symbolic image of a mighty oak dominating the surrounding landscape.85

Bloom insisted that all the trees in his drawings were dead.86 Like his paintings of corpses, these landscapes are primarily symbols of the universal cycle of life. In many of them, Bloom focuses on the shrubs and roots, where the natural process of growth, death, decay, and rebirth is most visible. On the floor of the forest, fallen branches and leaves revitalize the ground to give birth to the next generation, as worms and insects colonize the dead wood and hasten the process of decomposition. The bottom of the forest, where light hardly penetrates, is like the entrails of nature, the center of its regenerative power. The large size of the drawings and the anthropomorphic shapes of the branches add a terrifying note to these metaphysical landscapes, which show the forces of nature at work.

GLAMOUR AND METAMORPHOSIS

Our painters cling to form like timid sculptors. Why do they look down on light? I saw an enormous world to explore here, a new vision to bring forth.

James Ensor 87

Although visitors to Bloom’s studio are rarely able to see the paintings in progress, as he carefully turns them against the wall before letting anyone in, they can marvel at the range of objects with which the artist surrounds himself. Already in 1950, Elaine de Kooning described seeing there, next to the phonograph Bloom built for himself and his records of world music, “his collection of Persian, Chinese and Japanese prints whose bright, elusive colors are picked up by the objects crowding the shelves in his studio: a Chinese silk ‘jewel tree’ with leaves of metal and semi-precious stones for flowers, a huge opalescent slab of highly polished petrified wood; a piece of copper slag a foot long; hammered copper cauldrons; sprays of dried red leaves; peacocks’feathers; a tiny blue humming bird; a large stuffed golden eagle; vases with iridescent glazes; chunks of mica.”88 Color and light are the common denominator of such an accumulation, to which Brian O’Doherty, in his own description of Bloom’s studio about ten years later, added: “a skull without a mandible, … a dried fish’s head hanging from a string, the naked skeleton trailing out of it like a bony feather, … some plaster masks he has made himself and a cast of an aged, female hand, … some faded gourds, knobbly with nodes, as if they had leprosy.”89 Each object calls to mind a Bloom painting or drawing, so immediate is the relationship between the visual private world of the artist and his art.

Today, Bloom’s Indian veena dominates the table in his studio, next to several richly colored velvet Torah covers. Pinned to the walls are a poster of Altdorfer’s Nativity, the photograph of a detail from Georges de la Tour’s Fortune Teller, and the cover of a book on Victor Hugo’s watercolors, among many postcards and clippings. On the floor, more postcards and photocopies from art books, as well as a few open books, on Turner, Grunewald, and synagogue architecture.”90 The array of objects described by de Kooning and O’Doherty can still be found throughout the house, where every table and shelf is covered with iridescent glass vases, carafes, and pots.

The collection of glass vases, which has inspired the luminescent quality of Bloom’s paintings since the 1940s, became in the 1980s the subject of large still lifes in which fifteen to twenty of them are assembled on a table and on the floor (fig. 57 and cat. 31). Bloom rendered their color and reflections with layers of fluid paint applied in loose and translucent brush strokes through which the previous layers show. The result is a rich, shimmering surface, without impasto. The still lifes are about “glamour,” Bloom explained. “The vases are symbols of glamour, color, shimmer, craftsmanship.”91 In other words, they are metaphors for painting itself. Fascinated with the depiction of light since his early pictures of chandeliers and Christmas trees, Bloom found in the glass vases objects that materialize his central preoccupation: how to represent the brightness of light with opaque pigments.

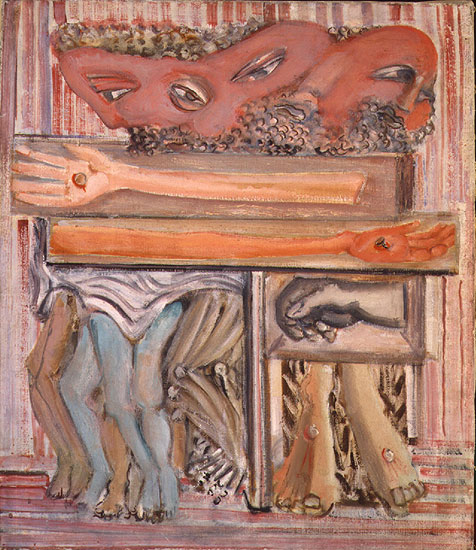

Iridescence and glow characterize another group of late paintings in which Bloom’s metaphysical concerns come together. These horizontal compositions, referred to as “leg paintings” by the artist because of the body parts that are depicted in some of them, resemble apocalyptic landscapes in which incandescent nature appears to be on fire. Their titles often evoke stages of metamorphosis or transition — Nightfall, Melting, Dissolving. In this dramatic vision of the universal cycle of life, every substance eventually merges into a primordial liquid. “All that is solid melts into air,” Karl Marx’s phrase to describe the transformation of modern life, can be applied to the fusion of mineral and organic in Bloom’s paintings. The glowing sunset colors match the intensity of the drama represented. In Melting (fig. 55), the fluid application of paint literally expresses the liquefaction of matter, while the short, impressionistic strokes suggest the disintegration of all that is solid. These late works recall a fascinating early work by Bloom, The Bride (fig. 24) of 1941, a painting of similar horizontal format in which the bride, lying down in a field of flowers that seem to engulf her, conjures up visions of the drowning Ophelia, as in Rossetti’s famous rendition. Like the “leg paintings,” The Bride represents a moment of transition, the passage from one state to another.

In the last ten years or so, Bloom has been working on a series of about forty paintings of Jews holding the Torah, rehearsing once more a theme he has never completely set aside since the early 1940s (fig. 63-64). The Jews are now older. With their beards, attenuated faces, and searching eyes, they increasingly resemble the artist himself. In contrast with the opaque application of pigment in the early portraits of Jews (fig. 26), the paint has become more transparent and dissolves the forms. The rapid, broad strokes of the gestural handling recall the open brushwork of the late Titian, displaying the same pictorial fluency of the artist who has mastered his medium. The Jew holds the Torah, the cornerstone of his faith, as a musician would his instrument, with an intensity and a fervor that communicate his spiritual engagement. The excitement of the paintbrush mirrors the transport of the subject. Working on many paintings at the same time, Bloom keeps going back to each canvas until reaching that moment of “getting a glimpse of the lost paradise,” which, in his words, marks the completion of a painting. 92

The portraits of Jews holding the Torah epitomize Bloom’s artistic enterprise. The Jew, for whom the Torah is the link between human and divine spheres, represents the painter himself, looking in his art for answers to his spiritual quest. The painterliness of the portraits emphasizes the role of paint handling in this search. “The expression is in the touch of the brush,” Soutine said. 93 Assimilating the painter to a mystic, Bloom uses the typical language of ecstatic visions to describe his own feelings: “When a day’s work has been successful, and you have a feeling of intensity and unity with the work, that’s the work you want to keep.”94 Faithful to an art more predicated on color than on line, and intent on giving painting the same emotional intensity that he found in music, Bloom has explored–and continues to explore–the expressive possibilities of color and light to suggest the ecstatic experience of the mystic.

Notes

The author wishes to thank Kimberly Lamm for the vast amount of research assistance that she contributed in the preparation of this essay and for her many valuable suggestions.

1 Dorothy Thompson, “The Spirits of Hyman Bloom: The Sources of His Imagery,” in Hyman Bloom (New York: Chameleon Books; Brockton, Massachusetts, The Fuller Museum of Art, 1996), 49.

2 Lecture at Pratt Institute, October 1958, in Dore Ashton, “L’Autumne a New York,” Cimaise 6 (December 1958), reprinted in Mark Rothko, 1903-1970 (London, The Tate Gallery, 1987), 87. Bloom amended Rothko’s quote when reading a draft of this essay, May 2002.

3 “A Gruesome Question,” in In My Father’s Court (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1962), 24-25.

4 Lois Tarlow, “Alternative Space: Hyman Bloom,” Art New England 4, 4 (March 1983): 14.

5 Dorothy Miller, oral history interview by Paul Cummings, 26 May 1970, transcript, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, 47–48.

6 For a detailed account of Bloom’s childhood in Latvia and his early years in Boston, see Thompson, “Spirits of Hyman Bloom,” 13–19.

7 John I.H. Baur, ed., New Art in America: Fifty Painters of the 20th Century ( Greenwich, Connecticut: New York Graphic Society in cooperation with Praeger, New York, 1957), 271.

8 Denman Waldo Ross, “An Experiment in Art Teaching,” October 1930, manuscript in Harold K. Zimmerman Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, reel 4961, frame 26.

9 Frederick S. Wight, Hyman Bloom (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1954), 4.

10 A large number of these early drawings are in the collection of the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

11 Judith A. Bookbinder, “Figurative Expressionism in Boston and Its Germanic Cultural Affinities: An Alternative Modernist Discourse on Art and Identity” (Ph.D. diss., Boston University, 1998), 130. Asked what he and Bloom used to go and see at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts when they were young, Levine replied “anything that had muscles.” Conversation with the author, 22 February 2001.

12 Denman Waldo Ross, The Painter’s Palette: A Theory of Tone Relations, An Instrument of Expression. Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1919)

13 Conversation with the author, 22 February 2001.

14 Ross (1853-1935) became a trustee at the MFA in 1895. See Edward W.Forbes, “Denman Waldo Ross,” in Bulletin of the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University 5,1 (November 1935): 2-6.

15 Created as a branch of New York’s Museum of Modern Art, it was renamed Institute of Contemporary Art in 1948. See Dissent: The Issue of Modern Art in Boston (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1985).

16 Wight, Hyman Bloom, 6.

17 Conversation with the author, 9 February 2002.

18 Norman L. Kleeblatt, “An Expressionist in New York: Soutine’s Reception in America at Mid-Century,” in An Expressionist in Paris: The Paintings of Chaim Soutine (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1998), 45-46. See also The Impact of Chaim Soutine (1893–1943): de Kooning, Pollock, Dubuffet, Bacon (Cologne: Galerie Gmurzynska, 2002), 12-13.

19 Pierre Pinchik (1893-1971) was born in Ukraine and emigrated to the United States in 1925. Bloom heard him sing in Boston in the 1930s and was most impressed by his performance. See Thompson, “Spirits of Hyman Bloom,” 22,

20 Herve Roten, Musiques Liturgiques Juives: Parcours et Escales (Paris: Citede la Musique/Actes Sud, 1998), 70.

21 Conversation with the author, 9 February 2002.

22 Quoted in Bookbinder, Figurative Expressionism,” 231.

23 Quoted in Jan Schwarz, “Death is the Only Messiah’: Three supernatural stories by Yitskhok Bashevis,” in Seth L. Woliz, ed., The Hidden Isaac Bashevis Singer (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), 109.

24 David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, 1962-1979 (Oxford:Thames and Hudson, 1985), 46.

25 See Bookbinder, “Figurative Expressionism,” 236–237.

26 Tarlow, “Alternative Space,” 15.

27 Jessica Snyder Sachs, Corpse: Nature, Forensics, and the Struggle to Pinpoint Time of Death (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Publishing, 2001), 20.

28 Medical and Surgical History of the War of Rebellion (1861–65) (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870–1888).

29 A copy of Holbein’s painting was at the Bush Reisinger Museum ( then called Germanic Museum), where Bloom saw it. The original, painted in 1522, is in the Basel Museum, Switzerland. Bloom’s skeleton painting is in the Saundra Lane Collection.

30 Fyodor Dostoyevsky, The Idiot, trans. David Magarshack (New York: Viking Penguin, 1955), 236. See also Julia Kristeva, “Holbein’s Dead Christ,” in Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989).

31 “I was very impressed with the paintings and studied them often,” Bloom said of the Isenheim Altarpiece (Bookbinder, “Figurative Expressionism,” 239). In 1997, while in Europe, Bloom went especially to Colmar to see the painting. On the influence of Grunewald on nine¬teenth- and twentieth-century artists, see Sylvie Raymond, ‘”Un Compagnon de lutte en esprit,’ Bocklin et Griinewald,” in La Revue du Musee d’Orsay 13 (Autumne 2001): 68–79; and Sylvie Lecoq-Raymond, ed., Regards Contemporains sur Griinewald (Colmar: Mus&e d’Unterlinden, 1995).

32 See Ann Stieglitz, “The Reproduction of Agony: toward a Reception¬History of Grtinewald’s Isenheim Altar after the First World War,” in Oxford Art Journal 12, 2 (1989): 91.

33 “Impossible Anatomy, 1895-1995: Notes on the iconography of a world of technologies,” in Identity and Alterity: Figures of the body 1895/1995 (Venice: La Biennale di Venezia and Marsilio Editori, 1995), XXVIII.

34 Quoted by Dore Ashton, New York Times, 31 October 1958, reprinted in Mark Rothko, 1903–1970, 86.

35 See especially Ziva Amishai-Maisels, Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on the Visual Arts (New York: Pergamon Press, 1993 ), 82; and Matthew Baigell, Jewish American Artists and the Holocaust (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 32.

36 “Bloom: Macabre Anatomy,” Art News 47 (February 1949): 52.

37 Tarlow, “Alternative Space,” 15.

38 Thompson, “Spirits of Hyman Bloom,” 35.

39 Letter to Kirk Askew, 3 March 1948, R. Kirk Askew Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

40 Reported by Sigmund Abeles in conversation with the author.

41 “Two Currents,” Time, 26 April 1954, 88.

42 Schnitzler’s Century: The Making of Middle-Class Culture, 1815–1914 (New York: W.W. Norton, 2002), xxviii.

43 Thompson, “Spirits of Hyman Bloom,” 53. Some critics interpreted Bloom’s corpses similarly. Emily Genauer, for instance, wrote about them: “They seemed, clearly, an allegory on present-day moral decay” (Herald Tribune, 14 March 1954, sec. 4, 10).

44 Pollock’s Number IA, 1948 is in The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

45 Elaine de Kooning, “Hyman Bloom Paints a Picture,” Art News 48, 9 (January 1950): 30-33, 56-57.

46 Erich G. Budde, “Helladic Greece” in Bulletin of the Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design 27 (December 1939): 5, fig. 6.

47 Letter, 3 March 1947, on file at the Addison Gallery of American Art. I am thankful to Julie McDonough, curatorial assistant at the Addison Gallery, for showing me this document.

48 John Algeo, “Kandinsky and Theosophy,” in Virginia Hanson, ed., H.P Blavatsky and the Secret Doctrine (Wheaton, Illinois: The Theosophical Publishing House), 222.

49 Whereabouts of The Stone are unknown. so Thomas B. Hess, Abstract Painting: Background and American Phase (NewYork:VikingPress, 1951), 118.s1 [bid.

52 Bernard Chaet, “The Boston Expressionist School: A Painter’s Recollections of the Forties,” Archives of American Art Journal 20,1 (1980): 28.

53 Bookbinder, “Figurative Expressionism,” 219–220.

54 Andre Breton, Surrealism and Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), 23.

55 Bloom to Kirk Askew, 3 March 1948, R. Kirk Askew Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

56 Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632, is at the Mauritshuis, The Hague.

57 See Spectacular Bodies: The Art and Science of the Human Body, From Leonardo to Now (London: Hayward Gallery, 2000), 23.

58 Francis Bacon–Hyman Bloom, The Art Galleries, University of California at Los Angeles, 30 October to 11 December 1960. The exhibition includ¬ed ten paintings by Bacon and seven paintings and seventeen drawings by Bloom.

60 “In Her Own Words: Interview by David Frankel,” in Helaine Posner, Kiki Smith (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1998), 36.

61 [bid., 32.

62 “Approaching Grace,” in ibid., 22.

63 Walter Benjamin, “Hashish in Marseilles,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings (New York: Schocken Books, 1986), 140.

64 Clemens E. Benda, M.D., and Max Rinkel, M.D., “Brief Account of Experiment with L.S.D.,” 24 April 1954, unpublished report, 2. I am grateful to Dr. A. Stone Freedberg for showing me this document. See also “Hallucinogen’s Effect Is Tested on an Artist,” Medical Tribune, 10 January 1966, 16.

65 Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception (1954; reprint, New York: Harpel & Row, Perennial Library, 1990), 27, 53.

66 Conversation with the author, 9 February 2002.

67 “Dr Max Rinkel is Dead at 71: An early researcher ofL.S.D.” New York Times, 10 June 1966.

68 See Martin Buber, Ecstatic Confessions, ed. Paul Mendes-Flohr (1909; reprint, New York: Syracuse University Press, 1996), 5.

69 See Patrick Werkner, “Gestures in Oskar Kokoschka’s Early Portraits,” in Oskar Kokoschka: Early Portraits from Vienna and Berlin 1909–1914 (New York: Neue Galerie, 2002), 31-35.

70 Conversation with the author, 9 February 2002.

71 John E. Bowlt, “Esoteric Culture and Russian Society,” in The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985 (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1986), 170.

72 Ibid.

73 Conversation with the author, 9 February 2002. 74 Tarlow, “Alternative Space,” 15.

75 After the death of James Rubin, in 1991, the collection was given to the Archive of World Music at Harvard University.

76 See Isabelle Clinquart, Musique d’Inde du Sud: Petit Traite de musique carnatique (Paris: Cite de la Musique/Actes Sud, 2001), 52-60.

77 Conversation with the author, 6 April 2002.

78 Ananda K. Coomaraswamy, The Danse of Siva: Essays on Indian Art and Culture (1924; reprint, New York: Dover Publications, 1985), 81.

79 Leon A. Kochnitzky, The Three Magi of Contemporary Music,” The Tiger’s Eye 3 (15 March 1948): 61.

80 Letter no. 242, 1882, The Letters of Vincent Van Gogh (New York: Penguin Classics, 1996), 208.

81 Conversation with the author, 10 February 2002. 82 Tarlow, “Alternative Space,” 15.

83 Thompson, “Spirits of Hyman Bloom,” 55.

84 Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (New York: Harper & Row, 1975), 184.

85 Caspar David Friedrich’s Solitary Tree is in the Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

86 Conversation with the author, 26 December 2000.

87 Timothy Hyman, “James Ensor: A Carnival Sense of the World,” in James Ensor, 1860-1949: Theater of Masks (London: Barbican Art Gallery, 1997), 82.

88 de Kooning, “Hyman Bloom Paints a Picture,” 31. Bloom has since clari¬fied that the “prints” are in fact reproductions and the “golden eagle” a peacock.

89 Brian O’Doherty, Hyman Bloom,” Art in America 49, 3 (1961): 47.

90 This description is based on my visit to Hyman Bloom’s studio of February 2002. A few months later, Bloom completed the construction of a new, larger studio on the ground floor of his house.

91 Conversation with the author, 26 December 2000.

92 Ibid.

93 The Impact of Soutine, 78.

94 Thompson, “Spirits of Hyman Bloom,” 33.

© 2002, National Academy of Design. Reproduced with permission

From Color & Ecstasy: The Art of Hyman Bloom, The National Academy of Design, 2002, New York, NY