The Bacon / Bloom Exhibition

by Robert Alimi, 2018

In 1953, Frederick Wight, Associate Director of Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), began working with Lloyd Goodrich, the Associate Director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, in planning a major Hyman Bloom retrospective which would open at the ICA in April, 1954. Wight wrote an insightful essay for the accompanying catalogue. The exhibition opened at the ICA and over the next 12 months traveled to the Albright, de Young and Whitney museums. Shortly after the plans were finalized for the Bloom retrospective, Wight left the ICA to take a position as director of the new Art Gallery at the University of California, Los Angeles. Over the next few years at UCLA, Wight organized shows for a variety of American and European artists including Hans Hofmann, Arthur Dove, Henri Matisse, and Pablo Picasso.

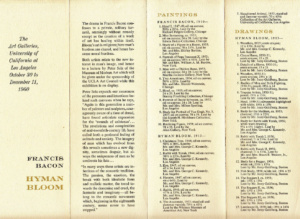

In 1960, Wight organized a two-man show of Francis Bacon and Hyman Bloom. The exhibition included 10 Bacon paintings, 7 Bloom paintings and 17 Bloom drawings; the show ran from October 30 until December 11, 1960. The majority of the Bloom oils came from the collection of George and Sally Kennedy. Kennedy had met both Bloom and Wight during his tenure as a geology professor at Harvard and had been a lender to Bloom’s 1954 retrospective. Kennedy, like Wight, left Massachusetts in 1953 to take a position at UCLA, in his case, to join the UCLA Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics.

In addition to sharing an overall focus on the human condition as subject, Bloom and Bacon had a bit more in common. The NY dealer Durlacher Bros. had Bloom solo shows in 1946 and 1948, and in late 1953 was preparing for another Bloom solo exhibition to take place in early 1954 while simultaneously presenting Bacon’s first solo show in the US. The Bacon exhibition at Durlacher Bros. opened in October 1953.

During the UCLA exhibition, MoMA curator Peter Selz gave a talk on the exhibition. In a 2017 conversation with me about the exhibition, the then 98 year old Selz reflected “Fred Wight had a very good idea to pair Hyman Bloom and Francis Bacon. It was a very good exhibition — Bacon and Bloom shared a common sense of despair for mankind.” As the exhibition reviews included below illustrate, the critics generally shared Selz’s opinions regarding the pairing of Bacon and Bloom.

The Exhibition Brochure

The drama in Francis Bacon confesses to a private, solitary turmoil, seemingly without remedy except as the creation of a work of art has healing within itself. Bloom’s art is religious; here man’s burdens are shared, and hence become moral burdens.

Both artists relate to the new interest in man’s image, and hence to a lecture by Peter Selz of the Museum of Modern Art which will be given under the sponsorship of the UCLA Art Council while this exhibition is on display.

Peter Selz expands our awareness of the pressures and intentions behind such canvases when he says, ”Again in this generation a number of painters and sculptors, courageously aware of a time of dread, have found articulate expression for the ‘wounds of existence’… The revelations and complexities of mid-twentieth-century life have called forth a profound feeling of solitude and anxiety. The imagery of man which has evolved from this reveals sometimes a new dignity, sometimes despair, but always the uniqueness of man as he confronts his fate…

“In many ways these artists are inheritors of the romantic tradition. The passion, the emotion, the break with both idealistic form and realistic matter, the trend towards the demoniac and cruel, the fantastic and imaginary’—all belong to the romantic movement which, beginning in the eighteenth century, seems never to have stopped.”

The Bacon & Bloom Paintings

Click on any image to start a slide show

( Images 1 - 10: © 2018 The Estate of Francis Bacon, images 11-17: © 2018 The Estate of Hyman Bloom)

The Bloom Works on Paper

(11 of the 17 Bloom drawings included in the exhibition are illustrated below)

Click on any image to start a slide show

(© 2018 The Estate of Hyman Bloom)

Reviews

- Imagery Returns - Henry J. Seldis

- The Way I See It - Jules Langsner

- Arts - Charles S Kessler

- ARTnews - Jules Langsner

Imagery Returns at UCLA Galleries

by Henry J. Seldis

LA Times, Sunday November 6, 1960

For more than 15 years the focus of attention in contemporary art has been on painters who made explosive gestures in which the image lost all coherence. Out of the recognition that essential unity of the sensory, emotional and rational elements is the desirable basis for a meaningful work of art comes the current reawakening of interest in the imagists of our time.

This emphasis is found, for instance, in the ensemble of exhibitions which will make the UCLA Art Galleries an especially popular place with Southern California gallery goers until Dec. 11.

An exhibition providing a revealing comparison of the paintings of Francis Bacon and Hyman Bloom; a promising show of works by 10 UCLA alumni and a remarkable selection of Marc Chagall prints constitute this varied and dynamic display. Though some of the young UCLA graduates prefer the non-objective approach, all of them come to their art as both thinking and feeling persons.

Keep Vision Intact

Neither Bacon nor Bloom suffer from the fragmentation of vision which has marked postwar painting. Images deriving solely from a rational assessment of the external world, without passion of the eyes, are only topographical records. Images without real roots in the environment are isolated graphs of a person’s inner workings. And the most beautiful combinations of color and shape, the most exquisitely measured proportions of line, area and volume, leave us where they find us if they have not grown out of a rational and emotional balance. The best works of Bacon and Bloom achieve that meaning in depth which finds at each level a corresponding level of human response to the world.

Bacon’s personages live in a nightmarish world of glass cages, obliterated features and silent screams. One can find an emotional equivalent to the terrifying beauty Bacon creates by his blurred images in the cage, trapped behind a transparent but impenetrable wall, in those slim Giacometti figures of whose presence we have no more than a hint. Only Giacometti’s impact is more lasting on the spectator since we are not disturbed — as we might well be with Bacon — by the uncomfortable but persistent thought that too much of Bacon’s effectiveness lies in his shock technique.

The most recent canvas in this exhibition does point to a drastic change in Bacon. The glass is off, the figure is raw and stark against a bright background. If there is shock here, it is at least visual, not literary.

Sumptuous Use of Paint

Bloom, whose sumptuous use of paint and ritualistic subjects gives his work an exotic flavor, offers us paintings which draw their form from the meaning they contain,

At best Bloom’s canvases have an inner radiance which envelops the spectator and removes him from the commonplace sensation that might otherwise be evoked by the portrait of a rabbi or the picture of a Christmas tree.

The Christmas tree painting reveals his capacity for sardonic comments. The related paintings of “The Anatomist” and “The Slaughtered Animal” are initially shocking through their paint quality rather than their subject matter.

Even Bloom’s most “unpleasant” canvases are undramatic, spiritually involved and moving, while Bacon at times seems self-consciously theatrical and isolated. It may be that Bloom’s paintings basically embrace humanity in its pitiful and defenseless mortality while Bacon rejects the emptiness and meaninglessness he finds in life.

Since Bloom, like Chagall, came from the religiously saturated Jewish communities in Eastern Europe It is interesting to compare certain elements in their work.

The Chagall prints, largely from the Grunwald Foundation and other significant local collections, offer an excellent opportunity to review his development as a graphic artist

The most encouraging aspect of the “10 from UCLA” exhibition is the catholicity at taste and the excellence of craftsmanship it represents.

Outstanding here are the eerie figurative statements of James McGarrell, the robust and dynamic abstract expressions of Harry Nadler and the muted richness of Jo E. Carroll’s canvases.

Noteworthy also are the Blakeish fantasies of Louis Lunetta, the vigorous and sensitive space explorations of Jack Hooper, the intaglio print by Raymond Brown and the Beckmannesque compositions by Lea Billet. Though evidently talented, Mike Todd, Roland Reiss and Les Kerr seemed least impressive to me at this stage of their careers. UCLA can be proud of the training its artist-students receive.

The Way I See It

by Jules Langsner

Beverly Hills Times, Oct. 1960

The Art Galleries at UCLA currently offer a tripartite exhibition well worth the effort of finding a place to park at the behemoth educational plant in Westwood. The three attractions at UCLA consist of Prints by Marc Chagall, presented by the Grunwald Graphic Arts Foundation, Ten from UCLA, an exhibition of paintings by graduates of the Art Department, and, finally, a two-man show of pictures by the English artist Francis Bacon and the Bostonian, Hyman Bloom.

Although both Francis Bacon and Hyman Bloom are widely acknowledged as significant contemporary imagists, the UCLA presentation marks their first appearance in Southern California. For the past quarter of a century these two artists have engaged the elusive problem of fashioning pictorial images of man in terms of twentieth century experience. Each of them brings to painting a relentless preoccupation with the emotional dislocations of life in our time. Neither of them skirts the anguish, terrors, brutalities, anxieties of existence in this golden age of science and technology. Consequently both have been subjected to such terms of abuse as morbid, depressive, cruel, cankerous, unhealthy, anti-humanist.

But then, I am certain both Francis Bacon and Hyman Bloom refuse to be rattled by the castigations of those who would have us “look only at the cheery side of things.” One doesn’t have be a venerable philosopher to recognize this is not the best of all possible worlds.

MOVING

Unless you are an indestructible Candide you are bound to find the paintings by Francis Bacon and Hyman Bloom profoundly moving, and, I hasten to add, disturbing in that both artists ore imbued with a tragic sense of life.

Of the two Hyman Bloom has been the least publicized. He is a reticent man who assiduously avoids the politics and hooha of the art world. Indeed he seldom admits people to his studio, and when he does, he is, likely as not, to face the pictures-in-progress to the wall. I suspect, however, in the long run the Bloom paintings will survive well, and that he is assured of a place as an important painter of our epoch.

With that assessment in mind I will devote the remainder of today’s column to Hyman Bloom, a rare bird among American painters, leaving the review of the UCLA exhibition to my colleague Charlene Cole.

At first glance the paintings of Hyman Bloom appear to be an exotic product of the Boston most of us know primarily through the fiction of J. P. Marquand. The art of Hyman Bloom is remote from the world of H. M. Pulham, Esq. But the Boston of the Lowells, the Cabots and the Lodges has undergone vast changes in the last half century. Tidal waves of immigrants have changed the complexion of the city. Among these immigrants have been the Irish Catholics of whom presidential candidate John P. Kennedy is a representative. In addition to the Irish and the Italians, Boston numbers a large colony of Jews of Eastern European extraction.

TOP NOTCH ARTIST

Hyman Bloom is one of a number of top-notch Jewish artists reared in the slums of Boston, the best-known of these Jewish contemporaries being the painters Jack Levine and David Aronson.

Happily for Levine and Bloom, they came under the influence at an early age of an influential teacher, Denman Ross, at the art school of the Boston Museum. Ross made his students aware of the rich heritage of art without imposing his own approach to painting with the encouragement of this splendid teacher.

There is a deep religious streak in Hyman Bloom. He wisely has allowed that tendency to shape his art from the beginning. Thus he turned to the works of such artists as Rembrandt, Rouault and Soutine as sources of influence. From these painters he gained insight into the problem of transmitting intense mystical feelings into pictorial images.

The measure of Bloom’s achievement can be found in the transformation of internal states of being into pictorial equivalents. The spectator experiences these intensely-felt states of being in the language of painting. That is to say, the swaying synagogue interiors, the venerable Hebrew scholars, the cantors, choir boys, bearded worshippers, Torah scrolls that long have engaged Hyman Bloom exist as complete visual entities. The viewer does not have to be acquainted with Jewish lore to be fully responsive to his symbolic imagery. If Bloom has returned again and again to the mystical rapture that is part and parcel of ancient Hebraic life, he also, at times, confronts head on the callous brutality continuously present in twentieth century “civilization”. Thus Bloom has taken to painting “visceral subjects” —carcasses of beef, surgical operations, as in two of the key works currently at UCLA.

Whether imaging the tragic solemnity of the synagogue or a dismembered carcass, Bloom invests his themes with a richly jeweled, luminous, vibrantly-hued surface. Thereby he adds tension to these images, and thus increases their power to involve us in them, Hyman Bloom is a passionate artist in an age that considers demonstration of emotion somehow ill-mannered. Moreover he has committed himself without reservation to realizing his emotional life to the fullest as a painter, a precarious enterprise, and one in which, he has succeeded admirably, as you can see for yourself.

LOS ANGELES: BACON, BLOOM, LEBRUN

By Charles S Kessler

Arts 35, 4 (January 1961): 14

Around election time, exhibitions of work by Francis Bacon, Hyman Bloom and Rico Lebrun brought “New Image” Expressionism to the fore in Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. A striking Bacon-Bloom show was mounted by the University of California at Los Angeles, and three exhibitions of Lebrun drawings were presented in Santa Barbara — at the gallery of the University of California at Santa Barbara, at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, and at the gallery of Esther Bear. The UCLA exhibition drew attention again to the theme of man “in a time of dread,” which Peter Selz introduced a little over a year ago at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The recent drawings by Lebrun shown at UCSB, including some cartoons for the mural at Pomona College on which the artist is now working, also belong emphatically to the new imagery of dread.

In the UCLA exhibition Bacon was represented by ten paintings of the last decade, including two of his exacerbated travesties from Velazquez and Van Gogh. Projecting a nightmare vision of tabloid humanity drawn from contemporary news photography and the films, Bacon’s most arresting pictures are utterly infernal displays, as in an artfully illuminated waxworks, of mauled images of demagoguery surrounded by spitted carrion. Dramatic, almost electric contrasts of tone (the expressionist luminism of Tintoretto comes to mind) and the simple opposition of fairly intense complementaries augment the theatrical punch of this sensational imagery of revulsion, which is otherwise conveyed in the Surreal manner of photomontage. Two Americans, a more modest but no less pungent statement of murderous resentment, takes revenge on two representatives of the hearty, good-naturedly rapacious type by smudging and blurring the features of their energetic and open-mouthed faces. In his recent reclining-figure compositions, Bacon complements his imagery of anger and violence with one of paralysis and naked abandonment.

In contrast to Bacon’s surreal journalism, Hyman Bloom’s approach to horror is quietistic and luxurious; yet the Poe-esque morbidity of his Anatomist and Slaughtered Animal affects us in somewhat the same way as Bacon’s savage commentaries on the essential indignity of man. Bloom’s anatomist, known only by his fastidious, patient, blood-soaked hands, is almost as scary a fellow as one of Bacon’s late-news grislies, and the corpse he investigates remains so much sliced-up meat, for all its chromatic gaudiness. Balancing this delicately drawn image of raw horror were several mellower, more painterly talismans of hope: Christmas Tree, Rabbi and Rabbi with Torah. Seventeen drawings showed Bloom’s sensitivity and skill as a draftsman, beginning as early as 1925 when the artist was twelve.

Twenty years ago, Rico Lebrun was also known for his virtuoso draftsmanship, and the sharp, precisionist line that once characterized his style (before Guernica became a gratuitous influence on his work during the forties) is seen at its best at the Santa Barbara Museum in such large, highly disciplined figure drawings as Seated Woman and Seated Clown. But in his recent drawings, the former classicist explores what he calls the geometry of pain. Exercises in monstrous invention, these drawings also represent, after the Cubistic Expressionism of a decade ago, a decisive return to the model: an aging Willendorf Venus chosen for her monumental volumes and the pathos of her decaying physique. Drawn with a deliberately uglifying line and modeled with planes of gray wash, the naked human body metamorphosed by means of drastic anatomic displacements into a vivid symbol of the organically inoperative and the spiritually appalling.

Bacon, Bloom

by Jules Langsner

ARTnews 59 (December 1960): 46.

A trio of shows—Francis Bacon paired with Hyman Bloom, “Ten Painters from U.C.L.A.” and Chagall prints are on view at U.C.L.A. Neither Bacon nor Bloom previously have exhibited here and both are bound to find responsive audiences, if only because each, in his separate way, transmutes into pictorial terms the persistent anxiety afflicting the age. Of the two, Bacon is more likely to exert influence on local painters, his out-of-focus imagery approximates the devices of some local artists. I am more impressed by the Hyman Blooms, notably the curiously Redon-like, 1947 The Eye, and Christmas Tree from 1944, when Bloom was under the spell of Soutine.

Of the “Ten Painters” all graduates of the U.C.L.A. Art Department, James McGarrell easily is the most mature and realized of the group; the remainder are still in the process of assimilating influences. Jack Hooper, Louis Lunetta and Robert Reiss evidence most promise.

Chagall prints (from the Grunwald and McLane collections) reveal the full graphic range of this master of fantasy.