The Drawings of Hyman Bloom: An Artist's Appreciation

by Sigmund Abeles

© 2002, National Academy of Design. Reproduced with permission From Color & Ecstasy: The Art of Hyman Bloom, The National Academy of Design, 2002, New York, NY

- Drawings by Hyman Bloom by Bernice Davidson, 1957

- Eight Drawings by Hyman Bloom by Hyman Swetzoff, 1962

- The Drawings of Hyman Bloom by Marvin Sadik, 1968

- Hyman Bloom: The Lubec Drawings by Philip Isaacson, 2001

- The Drawings of Hyman Bloom by Sigmund Abeles, 2002

- Hyman Bloom: A Survey of Works on Paper by Robert Alimi, 2024

I was introduced to the art of Hyman Bloom at about the same time that I discovered art for myself, in my mid-teens. As I was struggling to teach myself without the benefit of public school art classes and few other cultural opportunities in the small South Carolina town in which I grew up, it seemed to me that acquiring the ability to draw had to be the foundation of all visual art. Then, as if sent by the gods, a young graduate of Karl Zerbe’s class at the Boston Museum School, Gerard Tempest, landed in my hometown, following a traveling fellowship that afforded him the opportunity to work as an apprentice to Georgio de Chirico. I was quite shy, but I finally worked up the nerve to meet him. Tempest became my mentor. So I cut my art teeth being initially steered toward Boston Expressionism. “See these amazing drawings of wrestlers, well, they were made at about the same age you are now and they, and all of Bloom’s work, stand shoulder to shoulder to any art ever made,” Tempest said, as we poured over the few reproductions available of Bloom’s art at the time. “There are many strong figurative artists in or from Boston, but Hyman Bloom is by far the singular master of the Boston School and indeed is a world-class artist. Learn everything you possibly can from his works and his methods. Push yourself to your limits. Live drawing!” Tempest instructed me, and it was not difficult for me at this formative age to completely oblige.

I was introduced to the art of Hyman Bloom at about the same time that I discovered art for myself, in my mid-teens. As I was struggling to teach myself without the benefit of public school art classes and few other cultural opportunities in the small South Carolina town in which I grew up, it seemed to me that acquiring the ability to draw had to be the foundation of all visual art. Then, as if sent by the gods, a young graduate of Karl Zerbe’s class at the Boston Museum School, Gerard Tempest, landed in my hometown, following a traveling fellowship that afforded him the opportunity to work as an apprentice to Georgio de Chirico. I was quite shy, but I finally worked up the nerve to meet him. Tempest became my mentor. So I cut my art teeth being initially steered toward Boston Expressionism. “See these amazing drawings of wrestlers, well, they were made at about the same age you are now and they, and all of Bloom’s work, stand shoulder to shoulder to any art ever made,” Tempest said, as we poured over the few reproductions available of Bloom’s art at the time. “There are many strong figurative artists in or from Boston, but Hyman Bloom is by far the singular master of the Boston School and indeed is a world-class artist. Learn everything you possibly can from his works and his methods. Push yourself to your limits. Live drawing!” Tempest instructed me, and it was not difficult for me at this formative age to completely oblige.

Over time, I learned to question almost everything, but the strength and mystery of Bloom’s art, the drawings especially, certainly hold up, and they do more than that…they continue to haunt my days and nights, to astonish and reveal new levels of feeling and meaning.

Perhaps the most fascinating part of this story is just how Bloom and his fellow Boston prodigy, Jack Levine, were trained to draw from memory and from their imagination as masterfully as they did. Harold Zimmerman, who began instructing the two young boys when they were fourteen and twelve, respectively, stressed that art must come from one’s memory or imagination and forbade his students to work from life. The real dialogue was between the draftsman and his paper. It was okay to have anatomy books, reproductions of master art, or whatever stimuli that could assist, as long as they stayed in another room. The students were encouraged to remember an event or situation recently seen. Then, with no visual references except one’s sheet of paper, they struggled to make complete, convincing drawings, not isolated parts, but whole ensemble compositions, possessing rhythm, structure, proportion, anatomy, and content. They always began by putting a margin on the paper to create a frame within which to compose the picture. Zimmerman had them hold the pencil in a special way, over the forefinger and under the thumb, very lightly and relaxed, “so that the pencil follows your fantasy on the paper,” Bloom explained. Using always the same HB pencil but applying different pressure, they would start with extremely light lines and gradually add marks all over the paper, creating the whole picture at once.

The fellows were encouraged to return to the wrestling or boxing matches, or to concert halls or the events in the streets (there is a fine early Bloom drawing of an organ-grinder and his monkey), but when at work on these sustained drawings, each young artist was required to be alone with his developing abilities to recall, visualize, and conjure. Both Levine and Bloom bought into this nonacademic methodology, and it has to be said that the discipline is responsible for the masterful strength and uniqueness of their work. Once one owns the ability to draw anything seen or imagined, the artist has an arsenal of expression, one that goes far beyond skill, that he retains for life.

(“Color & Ecstasy” cat. 38)

Man Breaking Bonds on Wheel (fig. 1) exemplifies the level of Bloom’s precocious mastery found in even the very early works, developed under Zimmerman’s disciplined training. Bloom was sixteen years old when he came up with this compelling, struggling image. Yes, he was already well aware of the art of Michelangelo, Rubens, Blake, and most probably another earlier Boston eccentric, visionary, and anatomist, William Rimmer. But copying was never a part of Bloom’s training. Instead, he learned to memorize, analyze, and get to the essence of these older artists’ ideas and understanding of intention, proportion, and structure with strong emphasis on composing using the abstract elements of geometry and rhythm and applying these principles to the entire page. And last but hardly least, to express emotion was a constant goal. No doubt, in-depth study of the work of the great masters added greatly to Bloom’s drawing arsenal.

The huge, powerfully built,bound male portrayed in this drawing would today be referred to as a superhero. Surely, the boy artist also thought of him in similar terms. The very idea of a man of great strength, a Samson or other mythical hero breaking his bonds, was likely connected to Bloom’s own breaking with his family and religious training at such a tender age. He was substituting familiarity for a total involvement in perfecting his gifts, learning to draw the figure more and more masterfully at a wildly rapid rate. As the contours got more and more refined, even exaggerated to emphasize great power, there is the dual motion of the turning on a rack-like wheel at the foundation of the page and then moving upward over the massive torso toward the main energy of the muscular arms and hands, with the man’s head playing a huge part in conveying the action. Nothing is tentative, neither the means of the drawn lines that emphasize bursting volumes nor the ambition of this struggle for freedom over bondage, which is created by suggesting tension throughout the entire body. The final effect is of a contained cyclone.

(“Color & Ecstasy” cat. 39)

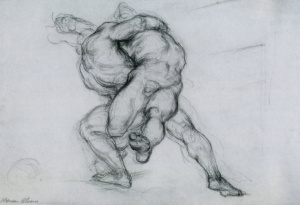

A similar powerful effect can be seen in Wrestlers (fig. 2),drawn when Bloom was seventeen. Here one is confronted with violent push-me-pull-you action that makes this packed composition unique. The searching lines that build this contest, rendered with a softer, darker pencil, are much looser and more fluid than in Man Breaking Bonds on Wheel. As in both Rubens and Degas, searching lines add to the sense of action as we witness the actual thinking process of the draftsman reconstructing one moment recalled from a previous night of wrestling.

Bloom and Levine shared a studio for a while in Boston and weathered the Great Depression by joining the ranks of so many artists who were given government funds to continue their art, in the form of small but manageable and steady salaries paid by the WPA Arts Program. Levine’s subject matter increasingly reflected the economic hard times of the Depression in biting political satire. Eventually, he moved to New York and became a well-known, successful player in the art scene, until the ascension of the Abstract Expressionist movement almost cancelled out the careers of even the best representational humanist imagists.

Bloom stayed in Boston, by choice, living very quietly, patiently developing his personal themes and dipping deeper and deeper into himself. He was by nature highly introspective, a religious seeker with a mystical and philosophical bent. His art was informed by personal experiences with the occult via seances, psychoanalysis, experiments with LSD, voracious reading, and the daily practice of studio work. One essential aspect of this artist that compelled me from the very moment I saw the work in reproduction — and that still holds me today — was that he made Jewish imagery, unabashedly, one of the central themes of his work. In my own very limited experience growing up in a Jewish family comprised solely of small-business people who moved from New York to the Deep South, drawing and painting and artists were not given any consideration by my Mother or aunts or uncles. Seemingly, they had no way to relate to art except to know one could never make a living doing it. I was aware that up North and in Europe before World War II, there were Jewish violinists and writers, mainly because my mother loved classical music and read. Crazy as it seems, I knew Bloom before I’d seen or even heard of Chagall or Soutine or Modigliani.

(“Color & Ecstasy” cat. 48)

Bloom holds a lifelong respect for William Blake and Albrecht Durer, as well as for Rodolphe Bresdin and Odilon Redon. Among his contemporaries who worked mostly from their heads, I feel two others are in his league for draftsmanship, Rico Lebrun and Pavel Tchelitchew. And then there are the obsessive, dark, haunting works of Ivan Le Lorraine Albright. All the above were strong, unique artists whose internalized art has little to do with any school of art and much to do with an isolated individual with brooding emotions brilliantly communicated.

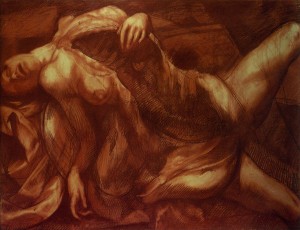

In the 1950s, Bloom made large drawings of corpses related to his paintings of similar subject. The grand-scale Female Cadaver, 1954 (fig. 3), a fully realized sanguine drawing, is so terrifyingly disturbing, yet also truly impressive, deeply felt art, its content unlike any other works of art I know. The autopsied woman, despite the unbelievable violation of her wide-open torso for medical purposes, is shockingly sensual in a Bernini’s St. Theresa-like swoon, her final one. For once — it is rare in Bloom’s work — the artist drew a young, attractive woman. The horrifically huge opening from her crotch to her sternum is nothing less than vulval in form. Even the red chalk, which makes reference to old master drawings, here also reminds one of dried blood. A High Renaissance quality links the manipulated cadaver to Michelangelo’s marble carving of Evening in the Medici Chapel. Bloom’s drawing is grand in form, dark in intention, and haunting — one is completely unable to erase her from one’s memory. She is a unique and terrible beauty.

(“Color & Ecstasy” cat. 50)

The Law of the Fishes, 1956 (fig. 4), is a page of great energy and great menace. Even muffled by the medium of water, this drawing is almost audible. I am reminded of Berlioz’s Symphony Fantastique. The forceful movement drives one’s eye toward a central vortex close in form to much of the compositional devices of Abstract Expressionism, but in this dense work, it was also consciously created to express emotional subject matter. The viewer becomes awestruck by the consummate structure of precisely drawn fish devouring other fish. The anatomy and expression of the individual morphology of the many different fish add and build up to this swirling ensemble. Clearly, this is Bloom’s metaphor for both evolution and humankind’s endless warring on his neighbor, if for no more reason than the need to eat and to survive. Violence becomes a way of life, a necessity.

As in all Bloom’s white ink drawings on dark grounds, the work is done on Coloraid paper, which is a paper prepared with a finely, mechanically painted surface. All those Yale graduates who studied with Joseph Albers used this paper for their design projects and studies in the phenomenon of the interaction of colors. For Bloom, it simply became the ideal smooth surface on which his dip pen could flow and swiftly dart, cross, and crisscross with, in places, highly built-up tonalities, as here in this deftly described fishy hell. With their wide variety of densities and masterly calligraphic line, these drawings on dark paper resemble photographic negatives.

(“Color & Ecstasy” cat. 52)

Bloom used yet a different technique in Old Woman Dreaming, a gouache of 1958, which I find to be nothing less than miraculous (fig. 5). Is this crone snoring, or in the throngs of a death rattle, or simply totally silent? Her eyes can see nothing. Her elongated nostril seems to be taking in air, likely close to her last? If she could relate to us her last dream, what might it reveal?

Technically, Old Woman Dreaming is a loose grisaille painting, messy in places, deliberately blurred, smudged, or washed out, yet exactly on the emotive button. It is a bit like a huge blowup of a late Goya brush drawing. At the same time, it also has some aspects of a child’s big-brush tempera work, so freely painted and open to discovery. We wish to look away from this obligatory visit to the aged, but find we can’t. The experience reinforces our mortality and yet we stand in front of a masterpiece for all time and all ages. Great art often appears deceptively easy; here is a prime example. The highly sustained series of monumental landscape drawings created by Bloom in the sixties were the result of his summer visits to Lubec, Maine, where the family of his former wife and good friend Nina Bohlen had property. Lubec is the easternmost point in the United States and the dark old-growth forest meets the sea in this awesome and remote location. Here, Bloom’s imagination caught fire in his first whole hearted submergence into nature and outdoor light as subject, giving birth to this dense and uninviting, almost impenetrable, forest drawing series.

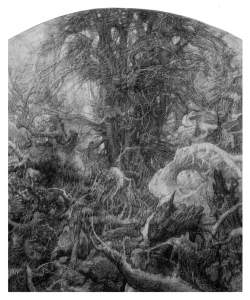

In each drawing, we are surrounded by a menacing thicket on a huge scale. The viewer is enveloped in an almost dark fairy tale forest and grows fearful.In Landscape #14 (fig. 6), for instance, we are blockaded by a foreground consisting of a profusion of massive, spiked branches. It is all a tangle, yet the artist does manage to make a pictorial order from the natural random chaos. This is absolutely no place to amble about or stretch out under a tree, but rather a harsh, lichen-covered, insect-infested forest allowing in just so much filtered light. Although Bloom took photographs of the dense forest for reference, he was true to his commitment to working from memory, and none of these drawings are from his photos.

(“Color & Ecstasy” cat. 59)

Bloom’s charcoal drawings recall the etchings and engravings of Northern European print makers like Albrecht Altdorfer, as well as the dense images of the nineteenth-century French visionary Bresdin. It helps one to know that hanging on the wall of Bloom’s sixth-grade classroom was a copy of Albrecht Durer’s engraving Knight, Death and the Devil (1513). It was at this time that Bloom was recognized as the class artist, and the strong, moving effect of Durer’s work has remained important in Bloom’s visual memory bank to this day. The distant landscape, which is far from the central theme of this profound image, is indeed harsh and spiky. Bloom’s landscape drawings are built up mark by mark, slowly describing forms and volumes as well as light and shadow. In the darkest of Rembrandt’s etchings, once one’s eyes adjust, it is possible to see into his darks. They never become flat blacks. This, too, is the case of the amazingly dense markings in Bloom’s mysterious Lubec landscapes.

My teaching career began in New England in 1961. I made a trip to the drawing room of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard to see its considerable collection of the early works of Bloom and Levine. Archival awareness had not arrived, because these piles of most impressive drawings by teenagers were kept at the time in Filene’s suit boxes.

Teaching and working in the Boston area, I had the opportunity to sell one of my works through the Boston dealer Boris Mirski, who agreed to give me in exchange one of Bloom’s magnificently baroque and dynamic wrestlers drawings, done when he was sixteen, which was in Boris’s possession (fig. 2). At the time, this exchange cost me half a month’s salary as a studio teacher at Wellesley College (where earlier Bloom had taught for two years), and I had a small family to support, but I was compelled to own the drawing. That dynamic action-packed sheet has informed, intimidated, and delighted me for decades, each morning and evening that I pass it.

Once I had moved to the Boston area, of course, I desired to meet Bloom one way or another. There was that one incidence when I was in an art supply store and I heard the proprietor saying quietly, “Mr. Bloom” this and “Mr. Bloom” that, and I saw a trim, handsome intent man dressed in a dark business suit, white shirt, and dark tie. Later, it was confirmed that he was indeed Hyman Bloom. An artist I knew who knew him advised me that if given the opportunity, I should not attempt to talk with Bloom about art, that his favorite subjects were mysticism, Indian music, and restaurants, as he ate all of his meals out. Indian music was the only subject of the three of which I had much knowledge.

Later on, we were to meet very occasionally at events at the home of Harold Tovish and Marianne Pineda in Brookline. It was only after Hyman and Stella married and moved to the state I was living and teaching in, New Hampshire, that I felt comfortable being in his company. He is a bit in exile in a semi-rural setting without public transportation, although it works fine for someone who lives so much within his own head. He is surrounded by his own works, a library, collected objects, including antique glass and Torah covers and a good studio with a door. He is blessed with strong health and a long life, plus a terrific and sharp, if somewhat sardonic, sense of humor. He once remarked about his life in Cambridge, “How I loved being a recluse in a city with so many good bookstores and places to eat.”

One afternoon in the earlier nineties, after lunch together in a Greek restaurant in Nashua, I was invited for the first time ever into Bloom’s upstairs studio and allowed to view a good-size horizontal canvas that had a large leg across the foreground with rats eating their way through the dark, rotting flesh and running along and over the limb. In the background, a city was burning. The quality of painting was brilliant, the content horrifying. (The only other contemporary works that so ripped me apart emotionally like that were Jerome Witkin’s Holocaust paintings, overwhelming in scale and graphic horror.) Then Bloom quietly expressed, “I can see no other way, can you?”

With almost universal post 9-11 jitters, with Americans feeling vulnerable as never before, with fears fanned by far worse threats and possibilities, one can only hope against hope that this canvas is not prophetic, certainly not anytime soon! Meanwhile, despite the pessimism of that painting, and in spite of Bloom’s age, one must be aware of the optimism manifest in the fact that he recently completed a large studio addition, to house the very ambitious and youthful series of large canvases of swirling, twisting, expressionist rabbis grasping their Torahs, transported into ecstatic states that are literally jumping off the master’s brush.

– Sigmund Abeles