By Elaine de Kooning

ART News, Vol. 48, No. 9, Jan 1950. Reproduced with permission.

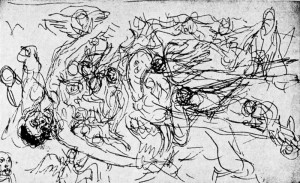

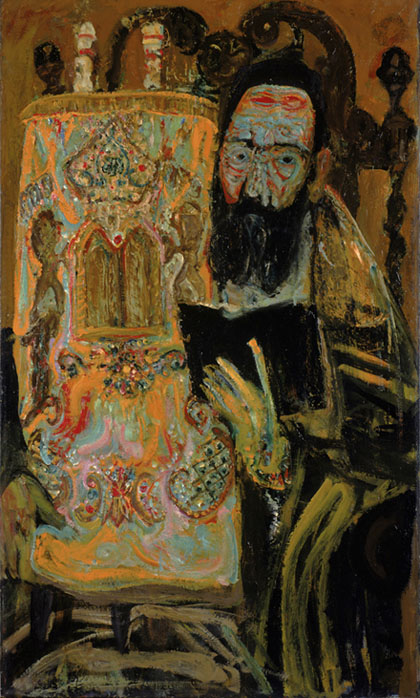

A rabbi, remote in grand proportions against an incandescent wall, a chandelier cascading in cut-glass pendants from the ceiling of a synagogue or a disemboweled corpse lying on an autopsy table — the subject of a painting by Hyman Bloom is as inseparable from its physical aspects as is the work of Grunewald or Rembrandt. Like these artists he seems to think with his brush; complex philosophical implications are conveyed in the action of painting. In one of Bloom’s recent large oils — The Harpies — composition, progressing toward total abstraction, seems to devour the subject, and the whole impact is carried in the boiling action of the pigment. Tracing a plastic motif through his work, one observes the refined interaction of technique and content; how the handling of pigment grows from one theme while it suggests another: A Christmas Tree gleams in flesh tones; the flowers and foliage around A Child in a Garden are formalized into a radiant Byzantine interior; or the same curdling brush strokes and spurts of color stud a brocaded Torah cover and the skin of the man who holds it. Complete, broad in scope and unified in a sense rare in contemporary painting, each picture by Hyman Bloom seems to be a direct culmination of all the subjects and techniques of his career and each is long in the making.

Working hours and places

The slight, attractive-looking artist has had only two one man shows since he and his friend. Jack Levine, “the boys from Boston,” made their first appearance in the Museum of Modern Art’s “Eighteen Americans from Nine States” show in 1942. Bloom’s output is very small – six pictures a year – or, more accurately, twelve every two years, since he works on a group at a time. There is no fixed method in this. He works on one picture every day for months, then puts it aside for an indeterminate period to work on others before he returns to it. And, in the same way, his daily working hours are varied. He may begin late in the afternoon and paint until two in the morning (the change from day to night doesn’t affect his colors; Bloom always works by artificial light in his rather dark studio) or he may start after he comes back from breakfast at ten or eleven. A bachelor, Bloom eats all his meals out in the various restaurants and cafeterias near his studio where he meets his friends —very few artists among them, but quite a few musicians. He collects records of Arabic, Armenian. Turkish and Hebraic music to play on the phonograph he built for himself. And related to this interest is his collection of Persian, Chinese and Japanese prints whose bright, elusive colors are picked up by the objects crowding the shelves in his studio: a Chinese silk “jewel tree” with leaves of metal and semi-precious stones for flowers; a huge opalescent slab of highly polished petrified wood; a piece of copper slag a foot long; hammered copper cauldrons; sprays of dried red leaves; peacocks’ feathers; a tiny blue humming bird; a large stuffed golden eagle; vases with iridescent glazes; chunks of mica. A principle of Bloom’s painting is demonstrated as the colors in these objects shatter their solid forms.

Early Lines and Colors

Subjects: death and religion

Most of Bloom’s subjects — from his first drawings of Absalom trapped by his hair in an oak, to his latest men at prayer or his desolate corpses —revolve around two themes, death and religion. But after the initial act of selection, his attitude toward them is curiously detached. He does not inject personal attitudes but presents a subject in the broadest frame of reference. (As a student, for instance, he was interested in the general effect of the symbols he used, but often did not bother to investigate their specific literary meanings.) Clinically portrayed, his corpses have a possibly unique position in Western art. The dead body has usually appeared as the victim of a particular situation. But on Bloom’s canvases death is defined as a process of nature, not an event in political or religious history, and the spectacle – without tragedy or moral – of a nameless corpse dissected by medical students or torn apart by harpies (here, simply symbols of decay) assumes its most terrify reality. Religion, as impersonally presented in the person of its anonymous followers, exists here as ritual. A striped four-corned prayer shawl, a golden chandelier or a Torah swathed in velvet evoke the clear and detailed description of measurements and materials in the Book of Exodus.

Although the artist is thoroughly familiar with his subjects (he received an orthodox religious training in Boston where he has lived since he came from Latvia at the age of seven) he is constantly searching for new visual aspects. His library has much source material – books on Eastern and Western European synagogues, catalogues of different ceremonial objects (he owns a Torah cover and prayer shawl); and for his corpses, medical and anatomical books (he also visits hospital dissecting rooms).

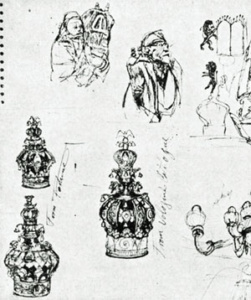

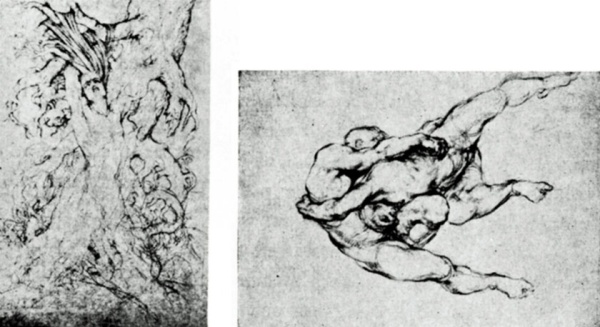

The same subject is drawn over and over — Bloom has filled innumerable notebooks—before, during and after the making of a picture—and much of his approach to painting can be observed in the elements he deals with in his sketches. Unusually small—ranging from an inch square to eight by ten inches— awkward and intense, they have the scale of his finished work. Scratching his pen-point across a page in short, rapid strokes that scuff up the paper, the artist can miraculously suggest blazing tones in a black and white drawing, or even represent configurations of pigment. Never facile, the quality of his line is fierce, compressed, opulent. Sometimes, as in the sketches for The Harpies, he scatters the pen-strokes to create a glittering, mobile surface, but more often he converges the separate strokes, reiterating contours until they become thick, resilient bands like those made with a heavily loaded brush. Unconcerned with consistency of finish, he often mixes his mediums. In a pen and ink drawing, he may carry one section further with show-card color (as in the old man; top center; page 32) or heighten details of a gouache with pencil. For his tempera sketches, often transparently washed over a completed pen and ink drawing, he uses a technique similar to that of his oils, achieving luminous, coppery tones as he glazes brilliant purples, oranges, reds and greens over one another, or wipes off wet layers of paint to uncover colors underneath. Except for the copies from magazines, catalogues or newspapers, his sketches are rarely vignettes floating unrelated to the boundaries of the paper. Whether roughed out in a few minutes or intricately developed like the temperas, the sketch is conceived in terms of the canvas and thus the artist almost invariably establishes a rectangle around it. When he is ready to start on a picture, he scales up the sketch to find the proportions of the canvas. Stacked facing the wall, the works-in-progress are remarkably varied —often “difficult” — in size and proportion, such as the many long narrow panels.

Similarly, he rarely uses all the colors spread out on his palette — a large sheet of glass — but he “likes to have them all there.” He lays out a fresh palette almost every day, often making slight adjustments, like a Mars yellow for an ochre, or cobalt for a Prussian blue. The texture and the weight of the paint are as important to Bloom as the tones. He likes the way zinc white dries, but finds it does not have sufficient body, so he adds an amount of white lead paste which he buys in 25 pound cans from Bocour. But, except for white, the pigment he uses most, he finds ready-made colors have too much oil, so he mixes powdered pigment in small quantities — enough to last a day or so — with his own medium, half dammar varnish, half stand oil. Unusually heavy, this medium resists the brush, qualifying his drawing and making his edges seem hammered out of metal. It dries fast enough to allow him to work on the picture the next day, but if the painting is put aside for any period, the artist, before working on it again, coats it with the medium to produce the tacky surface he likes to paint on, and also to soften the underpainting so that fresh colors are worked in and will not dry in a separate layer. Because of this method, his paintings do not crack despite the repeated use of varnish. Once his colors are mixed, he never adds more medium. If he wants a more fluid mixture or transparent glaze, he thins out the pigment with turpentine.