Expressionism: Boston’s Claim to Fame

by Nicholas Capasso

Originally published in Painting in Boston: 1950-2000

Originally published in Painting in Boston: 1950-2000

Edited by Rachel Rosenfield Lafo, Nicholas Capasso, and Jennifer Uhrhane

University of MA Press, Amherst, MA

© 2002, DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park.

Reproduced with permission

Regional styles in the visual arts are hard to come by in the history of American art in the second half of the twentieth century. Local identities were—and continue to be—obscured by the international hegemony of the New York art scene, and accelerating global interconnectedness via print, television, and computer-related media makes notions of regionality or locality obsolete, or even suspect. Despite these powerful forces, a few geographic areas have come to be identified with particularities of style or subject matter. The art historical canon now accepts, albeit marginally, two local postwar “movements”: San Francisco Bay Area Figuration, which includes the painters Richard Diebenkorn, Nathan Oliveira, and David Park; and the Chicago Imagists, centered on the work of Jim Nutt, Ed Paschke, and H. C. Westermann. Both of these regional phenomena enjoyed historical and stylistic integrity, produced important art, and represented isolated figurative camps that weathered the fifties onslaught of New York-based Abstract Expressionism. Boston, too, has a regional figurative style: expressionism, which has flourished and persisted here since the forties.

At mid-century, Boston was home to a vital, home-grown group of painters, the Boston Expressionists, at the apogee of their powers and reputations—and anyone paying attention to contemporary American art at the time knew it.1 As early as the thirties, the young Boston Expressionist painter Jack Levine began receiving national attention and acclaim. His work was included in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting in 1937, and the following year found his paintings in Three Centuries of American Art, an exhibition organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for the Jeu de Paume in Paris. In 1942, Levine was selected by curator Dorothy Miller, along with fellow Boston Expressionists Hyman Bloom and David Aronson, for her prestigious MoMA exhibition Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States. Aronson reappeared in Miller’s Fourteen Americans in 1946, again at MoMA. During the forties, Bloom, Levine, Aronson, and Karl Zerbe showed regularly in New York commercial galleries, and ARTnews began to identify and discuss the growing school of expressionist painting in Boston.2 Also in 1946, Bloom, Levine, and Zerbe found themselves among the important artists listed on Ad Reinhardt’s syndicated drawing How to Look at Modern Art in America, a semi-satirical art historical evolutionary tree with its roots in Post-Impressionism, a Cubist trunk, and branches and leaves representing then-current stylistic directions.3

And then there is Hyman Bloom, arguably the greatest of the Boston Expressionists in terms of both aesthetics and reputation. In 1950, his work was placed in the American exhibition at the Venice Biennale, alongside paintings by Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, John Marin, and Jackson Pollock, and Elaine de Kooning wrote an extended article about his creative process for ARTnews.4 In 1954, a Bloom retrospective, organized by The Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, traveled to venues across the country and culminated at the Whitney Museum. In the same year, his painting Apparition of Danger appeared on the cover of ARTnews, and within the magazine’s pages critic Thomas Hess heralded the Boston Expressionist as “one of the outstanding painters of his generation.”5

At the time, national visibility for a group of expressionist painters came as no real surprise. Just prior to the late-fifties consolidation of Abstract Expressionism’s critical, art historical, and market victories, Figurative Expressionism had been a dominant form of painting, not only in the hinterlands of San Francisco, Chicago, and Boston, but in New York itself.6 With the waning of Regionalism and Social Realism in the early forties came a broad-based resurgence of interest in figurative painting that sought to express emotional content about the human condition. Descriptive reality was abandoned in favor of a stylistic approach, heavily indebted to Munch, van Gogh, Picasso, and early-twentieth-century German Expressionism, which stressed formal metaphors for ineffable states of mind.7 Physiognomic distortion, evocative non-naturalistic color, bold lines, and virtuoso painterly brushwork erupted from intuitive (rather than analytic) creative processes, bent to the task of communicating what a subject feels like rather than what it looks like. It was surprising that the staid city of Boston could be a locus for such an outpouring of passion.

The emergence of a strong school of expressionist painting in Boston was no accident but the product of several interconnected attitudes, events, and personalities. The first inklings of a developing expressionist sensibility came in the twenties and early thirties with the emergence of Jack Levine and Hyman Bloom. Levine and Bloom both grew up in poor, immigrant Jewish communities in Boston’s South End and West End, respectively. Both boys displayed prodigious drawing skills early on and were avid students in public school art programs at the Museum of Fine Arts and in art classes held at neighborhood settlement houses. Word of their talents quickly spread, and they attracted the attention of two very important teachers, Harold Zimmerman and Denman Ross.8

Zimmerman, a student at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, supported himself by teaching at settlements and by tutoring individuals. In the mid-twenties, he took on both Levine and Bloom, separately, and began a course of instruction that steered both artists in an expressionist direction. First and foremost, Zimmerman’s pedagogical approach relied on drawing from memory, after intense observation of natural phenomena and great works of art. In this way, nature and art were valued but not imitated, and the imaginative faculties of the mind were held in greater regard than slavish copying. Bloom biographer Dorothy Thompson precisely described Zimmerman’s approach: “a method of drawing which relied upon the imagination and emphasized ‘picture making,’ the development of an organic unit denned by balance and harmony. The aim was to create a structure in which emotional intensity was achieved by the constant play of visual tensions, and completed when they were poised.”9 To support his teachings, Zimmerman introduced his charges to the work of Rembrandt and William Blake, and in 1931 he took them on a trip to the new Museum of Modern Art in New York to see, for the first time and firsthand, paintings by James Ensor, Paul Cezanne, Chaim Soutine, and Georges Rouault.

In 1929, Bloom and Levine—while still with Zimmerman—began studying together under Denman Ross, a 77-year-old patrician art collector, Harvard professor emeritus, and design and color theorist. Ross was in the habit of taking on private students to test the applicability of his theories, and he was so impressed with the two young artists that he paid them each a stipend of twelve dollars per week so that they could devote themselves full-time to their artwork and studies. Like Zimmerman, Ross believed in formal discipline at the service of the imagination, and direct study of great works from the history of art. To this he added an idiosyncratic approach to color relationships that was, according to Ross, an applicable scientific system that could yield universal harmonies of tone and value. Though Levine and Bloom were tutored in this chromatic arcana, they did not become unquestioning initiates. The value of this intense concentration on color for them was a rapid development of their skills as painters, deep sensitivity to color relationships, and a burgeoning appreciation for color as a means of emotional expression.

By 1933, as the boys became adults, they ended their studies with Zimmerman and Ross, rented a shared studio, and joined the Massachusetts section of the Public Works of Art Project (later the Federal Arts Projects of the Works Progress Administration) in order to survive by painting during the Great Depression. By the end of the decade, both artists were producing mature works in signature styles. They remained close until 1942, when Levine left Boston to enter military service; he then relocated to New York after World War II. And, even though their names were most often mentioned in the same breath, their works—while distinctly expressionist—differed in both style and subject matter. As Bloom described it, “Jack was interested in people and politics. Jack’s interest is in political philosophy; I’m interested in mystical philosophy.”10

In works of the late forties and early fifties, Levine established a national reputation for preaching a Social-Realist agenda with the agitated formal eloquence of expressionism. Benediction (1951, fig. 22) is a typical example.11 Here, three stylized and somewhat stunted caricatures enact a morally and politically didactic narrative: two wealthy politicos dance attendance on an inhered prince of the Church. Levine’s nervous formal vocabulary of rich colors, staccato brushwork, and fractured planes is particularly apt for this critique of the supposed separation of church and state— the painting’s surface looks like a smashed, and then reconstituted, stained-glass window.

Although Levine had decamped permanently to New York, he was still held up as an exemplar, a legend, a local-boy-made-good for a generation of younger Boston artists. Hyman Bloom, who stayed in Boston, found that his influence was even greater. Painter Lois Tarlow recalled:

In the late forties and early fifties the art community of Boston was small, like a neighborhood where everyone— artist, dealer, and collector—knew everyone else. As in most neighborhoods, however, there was one member who, everyone else acknowledged, was different. Hyman Bloom was unique among us. He did not attend one of the two accepted art schools but rather studied in a tutorial situation under two outstanding teachers, Harold Zimmerman and Denman Ross. He guarded his privacy and his time. He seldom went to openings, even his own, or hung around with other artists for mutual support and admiration. We knew he had a tap into the spirit world and was interested in Eastern philosophy, mysticism, occultism, and music.12

This mystical bent proved to be much more than just a beguiling aspect of Bloom’s persona. In 1939, the artist experienced a moment of deep spiritual insight: “I had a conviction of immortality, of being part of something permanent and ever-changing, of metamorphosis as the nature of being. Everything was intensely beautiful, and I had a sense of love for life that was greater than any I had ever had before.”13 Recapturing this shattering yet illuminating experience became the core of Bloom’s life work and study.

During the forties and fifties, Bloom chose bizarre, sometimes grotesque subject matter: corpses, autopsies, severed limbs, blazing Christmas trees and chandeliers, elderly nudes, mediums, séances, and roiling seascapes. He painted these images with bravura brushstrokes and saturated, opalescent colors in attempts to metaphorically turn matter into light, the dead into the living, and the material into the spiritual. At the heart of his enterprise was the quest of all mystics, to resolve and transcend the dualities that enslave the human spirit in the bonds of limited perceptual reality. Flayed Animal (1950-1954, plate 15)  in part a tribute to the butchered carcasses painted by Rembrandt and Soutine, is an animal unmistakably dead. Yet its vivid colors, slashing brushstrokes, dynamic, thrusting Baroque composition, and unblinking confrontational eye make this being somehow, powerfully alive. Bloom’s carcasses of the early fifties proceeded directly from his cadavers and autopsies of the mid-forties, works based on his observations of real dead bodies in the morgue at Boston’s Kenmore Hospital. The artist’s reminiscence of this experience helps explain his unique take on mortality, expressed visually in the cadaver and carcass paintings: “On the one hand, it was harrowing; on the other, it was beautiful-iridescent and pearly. It opened up avenues for feelings not yet gelled. It had a liberating effect. I felt something inside that I could express through color. As a subject, it could synthesize things for me. The paradox of the harrowing and the beautiful could be brought into unity.”14

in part a tribute to the butchered carcasses painted by Rembrandt and Soutine, is an animal unmistakably dead. Yet its vivid colors, slashing brushstrokes, dynamic, thrusting Baroque composition, and unblinking confrontational eye make this being somehow, powerfully alive. Bloom’s carcasses of the early fifties proceeded directly from his cadavers and autopsies of the mid-forties, works based on his observations of real dead bodies in the morgue at Boston’s Kenmore Hospital. The artist’s reminiscence of this experience helps explain his unique take on mortality, expressed visually in the cadaver and carcass paintings: “On the one hand, it was harrowing; on the other, it was beautiful-iridescent and pearly. It opened up avenues for feelings not yet gelled. It had a liberating effect. I felt something inside that I could express through color. As a subject, it could synthesize things for me. The paradox of the harrowing and the beautiful could be brought into unity.”14

Bloom began painting seascapes later in the fifties. In works like Seascape I, first series (1955-1956, repainted 1980), the artist depicts a slice of a much larger, and terrifying ocean where thrashing quasi-skeletal fish devour one another and dissolve into the surrounding waters. These paintings continue Bloom’s explorations of life and death and eliding states of matter, while addressing a somewhat darker theme. According to the artist, the seascapes are about “Eating, pursuit, and dying. It’s a euphemism for free enterprise, a predatory competition. Life is a contest.”15

Although Bloom turned increasingly to drawing as his primary medium in the sixties, and moved to nearby Nashua, New Hampshire, in 1978, his work continued to fire the imaginations of the emerging group of Boston Expressionist painters.16 And ultimately it was Bloom’s metaphysical and spiritual approach that was of far greater consequence locally than Jack Levine’s societal critiques.

Nowhere was Bloom and Levine’s influence more profound than among the faculty and students at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. David Aronson, a student and teacher at the Museum School—and also the artist who introduced Bloom to the Kenmore Hospital morgue—recalled that “Bloom and Levine were the key to the development of Figurative Expressionism at the Museum School. They inspired our interest in Soutine, Kokoschka, and Beckmann—in all the German Expressionists.”17 Indeed, Bloom and Levine did revere their European Expressionist forebears, and their work revealed this influence. But it was Karl Zerbe, who came to the Museum School in 1937 to lead its Department of Drawing and Painting, who almost single-handedly established expressionism as the basis of pedagogy in the visual arts in Boston for over two decades (fig. 23).

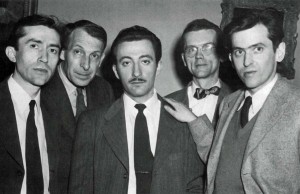

Members of the Modern Artists Group of Boston, meeting at the Old South Meeting House, Boston (left to right): Hyman Bloom,

Karl Zerbe, David Aronson, architect Robert Woods Kennedy, and Jack Levme, March 1948.

Courtesy Mercury Gallery, Boston, MA

Zerbe was born in Berlin in 1903, spent his youth and early career in Europe, and became a bonafide German Expressionist painter. He was instructed in rigorous craftsmanship and an expressionist aesthetic agenda at the Debschitzschule in Munich (a progressive forerunner of the Bauhaus) under Joseph Eberz and Karl Caspar, a follower of Edvard Munch. By the early thirties, Zerbe’s paintings displayed the influences of Oskar Kokoschka, Max Beckmann, and Georg Grosz, were collected by major German museums, and were shown by George Gaspan— Kokoschka’s dealer—in Munich. In 1933, he fled the Nazis, who would later include his work in their infamous 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition.18

When Zerbe arrived at the Museum School, he found an institution adrift. The drawing and painting program had been mired in stultifying, nineteenth-century academic pedantry and had not at all felt the effects of Modernism. Indeed, the visual arts in Boston as a whole were stuck in the past. The 1913 Armory Show, which introduced the radical avant-garde to American audiences, had a profound art historical impact in New York, where it was first exhibited, but its Boston showing provoked little response save generally hostile press. 19 Aside from the works of Bloom and Levine, painting in Boston in the twenties and thirties was dominated by an academic impressionism practiced by the followers of turn-of-the-century painters Edmund Tarbell, Frank Benson, William Paxton, and John Singer Sargent. Zerbe, Bloom, and Levine changed all of this, and their leadership made Boston Expressionism—at mid-century—the first truly Modernist art movement in the city’s history.

Zerbe took matters in hand immediately. He abandoned the school’s denatured Beaux-Arts instructional system in favor of the lessons he had learned in Germany.20 While he stressed discipline of technique and formal rigor, he also encouraged experimentation with painting media and expressive imagery. Like Zimmerman, Bloom, and Levine, Zerbe placed high value on individual expression and drawing from the imagination. And he preached respect for art historical tradition while lecturing with authority about the branches of Modernism that had informed his own work. These included the Cubism of Picasso and Braque and the German Expressionism of the Blaue Reiter group, Kokoschka, and Max Beckmann, all of which came as exciting revelations to his students.21 Yet Zerbe was never willing to abandon the figure and looked on the rise of Abstract Expressionism with disdain. At one point, Zerbe arranged for a show of Abstract Expressionist paintings at the Museum School but inserted into the otherwise legitimate exhibition a framed, paint-stained rag, labeled as the work of one P. T. Jackson—a conflation of P. T. Barnum and Jackson Pollock!22 And one of Zerbe’s star pupils, the painter Henry Schwartz, recalled that “In postwar Boston, expressionist painting was okay because the abstract movements sweeping the rest of the country were streng verboten, and those indulging in them were excommunicated.”23

In addition to his persuasive pedagogy, Zerbe was instrumental in bringing major expressionist artists to the Museum School to lecture and teach. In 1948, Max Beckmann visited the school, where an exhibition was held of his work. While there, he also delivered a talk on humanistic values in art and conducted critiques of students’ work. Zerbe also programmed a Museum School summer session at the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, which was directed by major expressionist artists: Ben Shahn in 1947, Mitchell Siporin in 1948, and Oskar Kokoschka in 1949.

Zerbe’s own work was marked by a mastery of, and a constant experimentation with, materials. According to his student Bernard Chaet, he was “involved with looking for a magic medium.”24 By 1938, Zerbe felt that he had found one in encaustic, an ancient and difficult process in which pigment is suspended in heated wax, dries quickly, lasts long, and allows a deep luminosity of color.25 With encaustic, Zerbe painted landscapes, portraits, and still lifes that were deeply indebted to Beckmann’s style and odd narrative juxtapositions of objects. Art historian Frederick Wight remarked that “a dreamlike, casual, and mysterious interrelationship of things is basic in Zerbe’s painting, and the feeling which he releases or conveys ranges all the way from somber grandeur to whimsy evoked out of the odd.”26 By the mid-forties, Zerbe adopted the Modernist themes of the harlequin and clown, and he used them as symbols of both alienation and a deeply felt spirituality, what critic Nancy Stapen referred to as “the most salient characteristic of Zerbe’s art … Its interiority.”27 Sometimes these single figures were obvious self-portraits, and sometimes, like Hooded Figure (1952, plate 16),

they were mysteriously masked. Zerbe left Boston in 1954 for the more salubrious climate of Florida, where he was appointed Professor of Painting at the state university in Tallahassee, a position he held until 1971. While there, his work became more colorful, more abstract, and more richly textured. These tendencies are all revealed in his Portrait of a Painter (Kokoschka) (1959), a tribute to his mentor, whose gesticulating image dissolves into a field of abstract shapes and broad brushstrokes.

At mid-century in Boston, Zerbe was not alone in his enthusiasm for expressionism. Art historian Judith Bookbinder has argued persuasively that cultural and educational institutions in Boston and Cambridge were marked by a pervasive germanophilia, and that this paved the way for the local embrace of Northern European Expressionist art.28 At Harvard University, for example, the Germanic Museum (renamed the Busch-Reisinger Museum in 1949) began collecting and exhibiting German Expressionist works in the thirties, with major shows of Georg Grosz in 1935 and 1941 and a Max Beckmann show in 1940. By 1950, it was the only area museum with an ambitious permanent collection of modern art, and it featured major works by Ernst Barlach, Otto Dix, Erich Heckel, Vasily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Paul Klee, and Emil Nolde.29

Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), while not a collecting institution, was just as avid in its embrace of European Expressionism. Founded in 1936 as the Boston Museum of Modern Art—a regional outpost of its parent museum, New York’s Museum of Modern Art— the institution changed its name in 1939 to the Institute of Modern Art to reflect its non-collecting status and to distance itself somewhat from MoMA. The Institute of Modern Art mounted several important exhibitions that added fuel to Boston’s expressionist fire: Contemporary German Art in 1939, a Georges Rouault show in 1940, and during the war years, exhibitions on Chaim Soutine, Marc Chagall, James Ensor, and Forbidden Art of the Third Reich. In 1948, the ICA was born when Director James Sachs Plaut issued a somewhat confused manifesto that in effect changed the institute’s name yet again and posited a mission favoring Northern European Figurative Expressionism in counter distinction to MoMA’s perceived francomania and promulgation of abstract art. In the wake of this declaration, the ICA mounted major exhibitions of the work of Kokoschka in 1948, Munch in 1950, and Ensor, again, in 1952.30 Boston’s august Museum of Fine Arts was a bit late to hop on the bandwagon, purchasing works by Kokoschka, Munch, Beckmann, and Kirchner shortly after the ICA exhibitions.31

All of these local expressionist resources were eagerly sought out by Zerbe’s students at the Museum School, among them David Aronson, Arthur Polonsky, Henry Schwartz, Bernard Chaet, and Lois Tarlow. These artists, along with Bloom, Zerbe, and Mitchell Siporin (see below), formed the core of what was nationally recognized as the Boston Expressionist group in the early fifties. While the practitioners of Boston Expressionism did not establish a thoroughly cohesive style, they did share several salient characteristics. They all abjured non-objective painting and relied on representation, particularly on images of the human figure seen alone or in narrative vignettes. To these images they applied an expressionist formal vocabulary that stylized and manipulated reality to make eloquent visual statements about ineffable feelings and universal humanistic themes that included religion, spirituality to the point of mysticism, artistic alienation, history, suffering and redemption, existentialism, human foibles, and the emotional resonance of nature. These themes were often inflected by the Jewish cultural heritage and immigrant experience or several of the artists. The Boston Expressionists also prided themselves on their technical abilities, especially their facility with drawing and acute color sense. They respected tradition, admiring not only twentieth-century European Expressionists but also expressionist heroes of yore: Michelangelo, El Greco, Rembrandt, Blake, and Goya. This reverence for the past, rather than the wholesale dismissal preached by the strictest adherents of Modernism, set the Boston Expressionists apart and branded them in the avant-garde circles of New York as conservative and backward-looking.

David Aronson was certainly the most influential of Zerbe’s students in Boston. Not only did he attend the Museum School beginning in 1941, he also taught there at Zerbe’s invitation from 1942 to 1955. In that year, when Zerbe left for Florida, Aronson was hired by Boston University to completely restructure the curriculum at its School of Fine and Applied Arts and turn the direction of instruction away from commercial art and toward fine art. In his new position, Aronson adopted Zerbe’s insistence on rigorous technique applied to individual expression, his position on the primacy of the human figure, his attitude of respect for the lessons of the past, and his admiration for European Expressionism. Aronson also hired several Museum School graduates—among them Arthur Polonsky, Reed Kay, Jack Kramer, Conger Metcalf, and John Wilson—to fill out his faculty.32 Thus the stronghold of expressionist pedagogy was transferred from the Museum School to Boston University.

Aronson’s paintings, while distinctly his own, bore important traces of Beckmann and Zerbe’s complex compositions in shallow space, Levine’s stylization of figures, and Bloom’s mysticism. At mid-century, Aronson was producing monumental narratives based on themes from the New Testament. To many, these subjects seemed odd, for like Bloom, Aronson was born in an Eastern European shtetl and was raised in the Jewish neighborhoods of Boston. But like many Jewish immigrants educated and acculturated in America, Aronson had deeply conflicted feelings about his heritage and felt that he must explore forbidden “graven images” and tackle traditionally Christian iconography in order to liberate himself to pursue a humanist agenda. As Aronson eloquently explained it:

Religion and art are two means of seeking ultimate truth. Religion has affinity for a great cross-section of humanity. Art is sympathetic to fewer numbers. A sincere art comes to judgment in unequivocal face value, endowed with effective power to stir a quest for the true. How fitting, therefore, to give expression through the medium of art, for freedom from imposed thinking in religion. Once this freedom is attained, we would say, religion gives peace of mind without premeditated dogma. The initial Scriptures are full of truths. They also abound in unconditional generalities that are open for specification and interpretation. It is just here that teachings have often been twisted, like the faces in some of my pictures. By intentionally employing the gentle and the grotesque in the same picture, I present this play of truth against duplicity.33

The artist also remarked, “I chose to paint Christian themes in order to participate with the Old Masters in themes they had painted.”34

One such work is Aronson’s Marriage at Cana (1947-1952, plate 17)  , an almost Byzantine hieratic stage show of events alluded to in the Gospel of John 2:1-12. But while the scripture is focused upon Jesus’s first public miracle— the changing of water into wine—Aronson is more concerned with the set of human themes that center around a wedding: love, celebration, spectacle, ritual, display, and hierarchies of class and personal relationships. Indeed, no single figure can be confidently identified as Jesus, the story’s traditional protagonist. Aronson conveys the emotions associated with this rich drama with jewel-like colors and active black outlines in musical rhythms, as well as a staggered succession of tight, shifting spaces. The artist’s later work has been, in general, softer, more atmospheric and lyrical, and less compositionally complex, focused on individual figures rather than large casts of characters. Aronson also took up sculpture in 1961, and he continues to create in both media.

, an almost Byzantine hieratic stage show of events alluded to in the Gospel of John 2:1-12. But while the scripture is focused upon Jesus’s first public miracle— the changing of water into wine—Aronson is more concerned with the set of human themes that center around a wedding: love, celebration, spectacle, ritual, display, and hierarchies of class and personal relationships. Indeed, no single figure can be confidently identified as Jesus, the story’s traditional protagonist. Aronson conveys the emotions associated with this rich drama with jewel-like colors and active black outlines in musical rhythms, as well as a staggered succession of tight, shifting spaces. The artist’s later work has been, in general, softer, more atmospheric and lyrical, and less compositionally complex, focused on individual figures rather than large casts of characters. Aronson also took up sculpture in 1961, and he continues to create in both media.

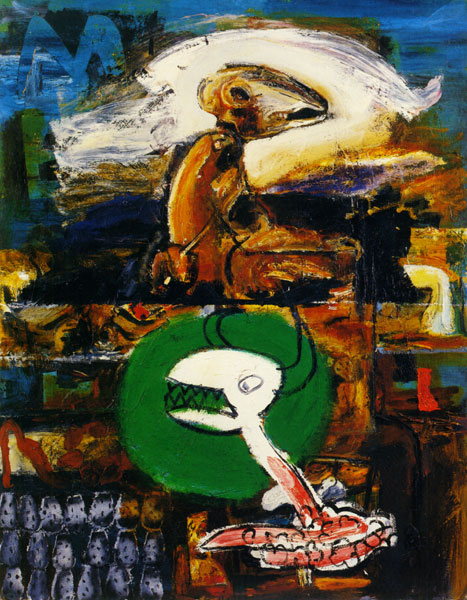

Arthur Polonsky’s work also contributed to Boston Expressionism’s legacy of mysticism. He sometimes adopted Biblical subject matter like Aronson, but more often his imagery is as uncanny as Bloom’s. And his work almost always reflects, in feeling, Zerbe’s dreamlike interiority, via Odilon Redon. Marine Samson (1959, plate 18) is a particularly apt example of all these tendencies. What this narrative—with its fey Samson, screeching bird, expiring horrific monster, and seaside setting—has to do with the story related in Judges 13 to 16 is anyone’s guess. Only the jawbone of the ass grounds the image in recognized Biblical iconography. But in true expressionist fashion, Polonsky is not interested in Samson’s tale per se but in sets of feelings, inexpressible with text, that illuminate the human condition. The artist himself has made this quite clear: “In all years, styles and dedications, whatever the utility, command or social assignment, the real work of the artist’s hand, tangent upon heart and mind, has been to symbolize and draw near the multiple possibilities of perception by which we animate with meaning the terrain of our being in the world.”35 What sets Polonsky apart from his immediate milieu is his Symbolist/Surrealist interest in psychological resonances created through irrational juxtapositions of beings and objects, and the ferocious brushwork with which he animates his astonishingly bizarre scenes.

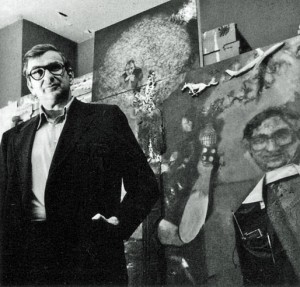

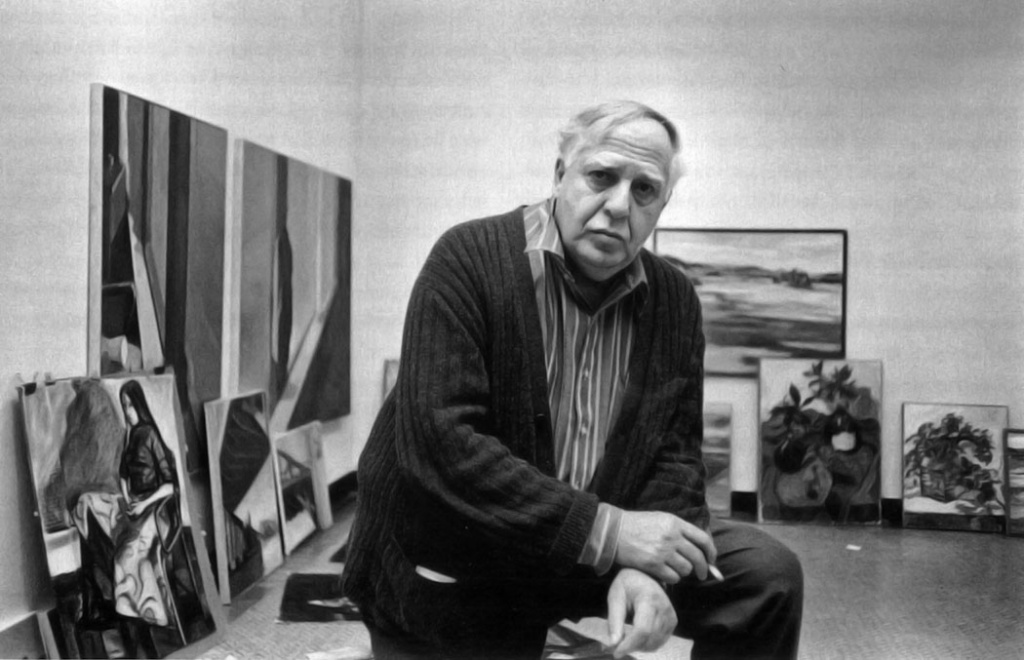

Henry Schwartz in his studio, 1982.

Courtesy Gallery NAGA, Boston, MA

Unlike many of his mid-century Boston Expressionist contemporaries at the Museum School, Henry Schwartz (fig. 24) developed gradually and did not create his truly major paintings until the eighties. His early work, which strongly bore the marks of Beckmann, Zerbe, and Aronson, gave way to a powerful personal style that involved a multifaceted mastery of paint application, lurching scales, seemingly wet surfaces, and a twisted trompe-I’oeil perfectionism bent to expressionist ends. This virtuosity positions Schwartz alongside Hyman Bloom, and Schwartz’s own student Gerry Bergstein, as the greatest masters of painterly technique in Boston since John Singer Sargent.

Schwartz is not a mystic but an intellectual deeply interested in the emotional content of history and culture. Schwartz devoted himself to experiencing and understanding the great nineteenth- and twentieth-century master-works of Northern European Romanticism, Symbolism, and Modernism, and then disgorging his meditations on their meanings and implications onto canvas. His researches went far past the visual arts, and included music and literature. He describes himself as “an avid concert-goer, record collector, and musicologist, and music became the spiritual center—a religion, really—around which my painting took orbit.” Schwartz went on to say: “Much of my art is narrative. The murals I have done are arranged like filmstrips peopled not so much with the events of my own life, although I appear in them, as with those of the minds that made the art I respect, like Joyce, Proust, Mahler, and that are necessary for the life of the mind.”36

[ Vienna Blood: Dirty Dancing on the Danube 1888-1938 (1988-1989, plate 20)  may well be Schwartz’s magnum opus. In this ambitious work, the artist combined aspects of history painting and portraiture with expressionist formal distortions to create an image resonant with deeply felt ambivalence about European cultural and political history. Across the bottom of the painting, a row of men appears. From left to right, they are Ludwig Wittgenstein, Adolf Loos, Oskar Kokoschka, Karl Krauss, Alban Berg, Johann Strauss, Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Sigmund Freud. Together, they represent the end-products of nineteenth-century German Romanticism, the pinnacle of philosophy and the arts in fin de siècle Vienna. While Schwartz deeply admires these men and their achievements, he is also painfully aware that the same culture that spawned their creative brilliance also funneled directly into the philosophical underpinnings of Naziism.37 The tiny figure of Adolf Hitler lurks below the intellectual giants, and the register of writhing, tortured female bodies above them is an allegory of the human and cultural rape and murder of the Holocaust. Thus, embedded in Schwartz’s work is a vastly intelligent yet uncomfortable and self-conscious deconstruction of expressionism itself. In psychoanalytic terms, Schwartz can be seen as Zerbe’s Oedipal son.

may well be Schwartz’s magnum opus. In this ambitious work, the artist combined aspects of history painting and portraiture with expressionist formal distortions to create an image resonant with deeply felt ambivalence about European cultural and political history. Across the bottom of the painting, a row of men appears. From left to right, they are Ludwig Wittgenstein, Adolf Loos, Oskar Kokoschka, Karl Krauss, Alban Berg, Johann Strauss, Arnold Schoenberg, Anton Webern, and Sigmund Freud. Together, they represent the end-products of nineteenth-century German Romanticism, the pinnacle of philosophy and the arts in fin de siècle Vienna. While Schwartz deeply admires these men and their achievements, he is also painfully aware that the same culture that spawned their creative brilliance also funneled directly into the philosophical underpinnings of Naziism.37 The tiny figure of Adolf Hitler lurks below the intellectual giants, and the register of writhing, tortured female bodies above them is an allegory of the human and cultural rape and murder of the Holocaust. Thus, embedded in Schwartz’s work is a vastly intelligent yet uncomfortable and self-conscious deconstruction of expressionism itself. In psychoanalytic terms, Schwartz can be seen as Zerbe’s Oedipal son.

Schwartz also played a key role in the transmission of expressionist values to a younger generation. After Zerbe’s departure in 1954, Schwartz was the only remaining dyed-in-the-wool Boston Expressionist left on the faculty at the Museum School, where he taught until 1990. Like Zerbe, he was a beloved teacher and became an important bridge between mid-century Boston Expressionism and the local manifestations of Neo-Expressionism in the eighties and later.

Three other painters—Barbara Swan, Bernard Chaet, and Lois Tarlow—studied under Zerbe at the Museum School, and while their early works all directly reflected their Boston Expressionist milieu, they went on to pursue paths that gently diverged from the heady humanism, mystical musings, and strict focus on the figure that predominated in the fifties. Barbara Swan is, as art historian Pamela Allara put it, “a Boston Expressionist in spirit if not in style.”38 This analysis was shared by Dorothy Adlow, venerable art critic for The Christian Science Monitor, who in her review of Swan’s first solo exhibition in 1953 wrote, “Barbara Swan is above all a portraitist … In painting, she combines the interest in personal characterization with decorative device and expressiveness of color. . . . Combined in the paintings are various influences—academic, expressionistic, neo-impressionistic.”39 Swan’s painting The Nest (1956, plate 19)  bears all of this out. In it, one can see her considerable academic skills in the renderings of anatomy and drapery. Yet the painting also reveals her expressionist training in its odd plunging perspective, use of evocative colors, and almost spiritual contrast of darks and lights.

bears all of this out. In it, one can see her considerable academic skills in the renderings of anatomy and drapery. Yet the painting also reveals her expressionist training in its odd plunging perspective, use of evocative colors, and almost spiritual contrast of darks and lights.

Swan—along with Lois Tarlow—also strikes an early feminist note in the almost all-male club of Boston Expressionism. This is a self-portrait of the artist nursing her infant son, Aaron Fink (a member of the next generation of expressionist painters in Boston). Swan continued to create works of art while assuming the duties of wife and mother in the late fifties and sixties, a time when a great many other women put aside or abandoned careers in favor of an exclusive focus on their families. With the composition of this painting, she also managed to avoid stereotypical Madonna and Child clichés and express honest and ambivalent emotions about motherhood and breastfeeding. Over the next few decades, the artist gradually adopted a more realist style, but her thematic focus remained on the complexities of identity within the format of portraiture. In her best-known works, Swan painted herself, and the images of others, amidst the reflections and refractions of studio still life vignettes of assembled glass vessels and mirrors.

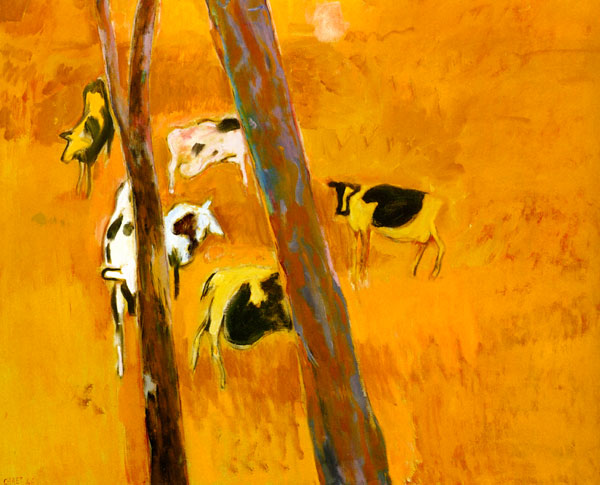

Bernard Chaet completed his studies at the Museum School in 1947, and in 1951 he was hired by Josef Albers to teach at the prestigious Fine Arts Department at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Although he remained at Yale until 1990, he remained a strong presence in the Boston art world, showing consistently at the Boris Mirski Gallery and later the Alpha Gallery. His early work was very much in line with the prevailing expressionist trends, with strongly drawn and richly colored figurative works that addressed profoundly humanistic themes. In his later work, he turned increasingly toward pure landscape—a major facet of expressionist interest that was given short shrift at the Museum School. Chaet became a great colorist and a master of the expressive possibilities that lie in the technical manipulations of paint: texture, impasto, and brushwork. In works like his Six Cows (1966, plate 22)  , one can discern the influence of early German Expressionist landscape painting, but also Matisse and prewar American Modernism. Chaet has faithfully carried the tradition of native abstract landscape, established by John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Arthur Dove, into the late twentieth century. About the cow theme, which recurs in his work, Chaet wrote: “This motif started when I was drawing landscape in Connecticut and some cows literally walked into my drawing space. I was attracted by the individual black and white shapes playing against the hills and foliage. I translated these drawings into paintings indoors.”40 Like a true expressionist, Chaet works as much from his memory and imagination as his observations of natural phenomena.

, one can discern the influence of early German Expressionist landscape painting, but also Matisse and prewar American Modernism. Chaet has faithfully carried the tradition of native abstract landscape, established by John Marin, Georgia O’Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and Arthur Dove, into the late twentieth century. About the cow theme, which recurs in his work, Chaet wrote: “This motif started when I was drawing landscape in Connecticut and some cows literally walked into my drawing space. I was attracted by the individual black and white shapes playing against the hills and foliage. I translated these drawings into paintings indoors.”40 Like a true expressionist, Chaet works as much from his memory and imagination as his observations of natural phenomena.

Lois Tarlow also became best-known as a landscape painter. Like Barbara Swan, her early work focused on portraits of her family and domestic scenes, in an expressionist style nuanced by academic drawing. But she truly came into her own in the seventies, when she began a series of large, stylized landscapes that imposed a lyrical, expressive order on unruly nature. Like Chaet, she paints from memory: As the North River Meets the Sea (1973-1976, plate 23)  , for example, was painted in her studio, based on her observations of the Marshfield, Massachusetts, saltwater marshes, which she had seen while driving by in her car.41 In this painting, she captures the unmistakable (at least to coastal New Englanders) look of the marsh but orders its pools into regressing blue crescents and enflames the foliage with reds and pinks. The image is not about the marsh per se but her experience of it, both visual and psychological. Later works by Tarlow became more formally agitated, and more concerned with environmental issues. But as the artist explained, “Through the years, some formal aspects of my work have remained constant. However representational my paintings may appear, abstraction has always been a strong impetus. Color is continually food for my spirit…. I like a surface achieved with apparent ease from a sensual enjoyment of the paint or pastel. These threads bind the years together.”42

, for example, was painted in her studio, based on her observations of the Marshfield, Massachusetts, saltwater marshes, which she had seen while driving by in her car.41 In this painting, she captures the unmistakable (at least to coastal New Englanders) look of the marsh but orders its pools into regressing blue crescents and enflames the foliage with reds and pinks. The image is not about the marsh per se but her experience of it, both visual and psychological. Later works by Tarlow became more formally agitated, and more concerned with environmental issues. But as the artist explained, “Through the years, some formal aspects of my work have remained constant. However representational my paintings may appear, abstraction has always been a strong impetus. Color is continually food for my spirit…. I like a surface achieved with apparent ease from a sensual enjoyment of the paint or pastel. These threads bind the years together.”42

Mention must also be made of Mitchell Siporin, a nationally prominent Chicago painter who came to Brandeis University in 1951 as the founding director of the Department of Fine Arts. For at least a decade prior to this appointment, Siporin had been in the same rough orbit as his Boston Expressionist contemporaries. With Bloom and Levine, his work was included in MoMA’s Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States; he had directed the Museum School’s summer program in the Berkshires in 1948; and, in his well-received work prior to World War II, Siporin had managed to create a persuasive blend of expressionist style and Social-Realist content not unlike Levine. About the painter’s imagery in the thirties and forties, Carl Belz wrote, “his figures are twisted out of shape, their heads and limbs are given exaggerated proportions, and the spaces they occupy are warped into nightmarish configurations.”43 Siporin specialized in depicting human suffering.

After the war, and increasingly into the fifties, Siporin’s themes became more gently satirical, his figures less grotesque and more caricatured, and his style more abstract, flat, and color-saturated. All of this is evident in Rockport Beach Scene (1955, plate 21)

, where the artist smiles at human foibles on parade at the seaside. Also evident is his work’s remarkable resemblance to many of the salient characteristics of Boston Expressionism: jewel-like passages of color, hieratic scale, ambiguous space, and a compositional debt to Beckmann and Zerbe. Surely Siporin’s work had been influenced by his exposure to the paintings he was encountering in local museums and galleries.44 Siporin’s teaching also took on an expressionist tone, and in 1954 he hired Arthur Polonsky, who would teach for ten years at Brandeis before moving to Boston University. With Zerbe and Aronson, Siporin became the third pillar of expressionist pedagogy in Boston.

Boston Expressionism thrived in the fifties and enjoyed a great deal of support in local museums and galleries, especially The Institute of Contemporary Art, DeCordova and Dana Museum (later DeCordova Museum and Sculpture Park), and the Boris Mirski Gallery.45 But nationally, none of the artists save Bloom, briefly, garnered significant attention, and the entire regional movement was ground under the heel of non-objective Abstract Expressionism and the dominance of New York as the new epicenter of global contemporary art. The Boston Expressionists—those discussed above and others (Sigmund Abeles, Leonard Baskin, Jason Berger, Alfred Duca, Reed Kay, Jack Kramer, Michael Mazur, Conger Metcalf, Joyce Reopel, Arnold Trachtman, Jack Wolfe, and Melvin Zabarsky)—stuck to their guns and bravely continued to create and exhibit Figurative Expressionist paintings, many to this day.46 In 1970, DeCordova director and expressionist sympathizer Frederick Walkey organized the exhibition Humanism in New England Art and summed up the prevailing aesthetic Zeitgeist:

Humanism is probably the dominant artistic fashion in New England—the one for which we are best known nationally; because it represents a tradition of nearly two decades and seems to be as viable today as twenty years ago…. The exhibiting artists share a profound sense of history and a dedication to tradition; they have very little in common with the “now-in” generation . . . these artists keep alive a tradition for brilliant draftsmanship, a respect for materials, and a mastery of fundamentals which gives them a freedom to express profound and subtle ideas.47

But this was strictly local. The international swan song of Figurative Expressionism, Peter Selz’s New Images of Man exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959, was not only excoriated by critics but also contained not a single painting by any Boston Expressionist.48 The phoenix, however, would rise from these ashes in the eighties.

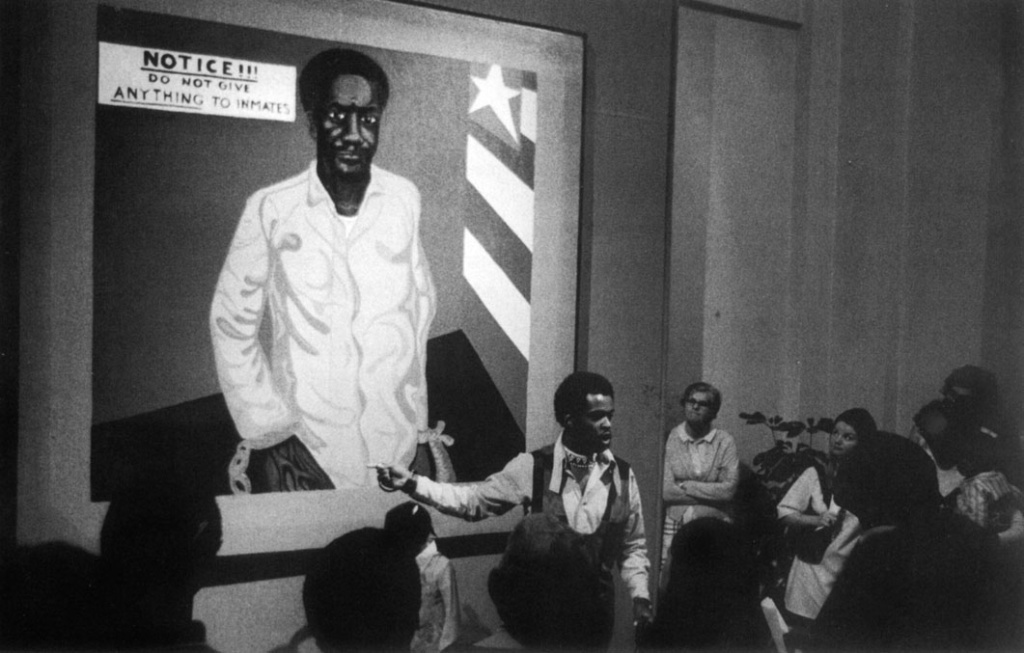

Dana C. Chandler (Akin Duro) presenting gallery talk for “Afro-American Artists: New York and Boston” exhibition organized by Museum of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, School of the Museum of Fine Arts, and Museum of Fine Arts, at the MFA, 1970.

Courtesy Northeastern University Libraries, Archives, and Special

Collections Department

The sixties and seventies saw several new but unrelated contributions to the local expressionist tradition. The first was the emergence of Dana C. Chandler (Akin Duro),49 a gifted African-American artist who had a wrenching and formative experience shortly after completing his studies at the Massachusetts College of Art. On June 5, 1967, Chandler (fig. 25) watched white police officers brutally disperse a group of African-American women who were staging a peaceful protest at a welfare office in Boston’s Grove Hall neighborhood. This horrific incident, as well as the rise of the civil rights movement nationwide, prompted the artist to devote his life and work entirely to addressing the social inequities fostered by racism in America. Chandler describes his entire oeuvre as

a picture story of an unrequited love for the vision of America described in the contemporary version of the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights, as painted by one of its Africanative American sons. I love this country, in fact I consider myself to be a super-patriot striving to make America live up to its vision of being the ‘Land of the free, home of the brave, with liberty and justice for all.’50

His chosen themes, while all centering on the African-American experience, have included oppression, economic inequity, the scourge of drugs, racial sexism, domestic violence, the societal emasculation of black men, the beauty of black women, the middle passage, slavery, apartheid, and portraits in homage to leaders in African-American history. This artistic activism puts Chandler squarely in the political tradition of expressionism that strove for social justice, as evidenced in the work of van Gogh, Barlach, Beckmann, Grosz, Kollwitz, and locally Siporin and Levine. But while all his art historical predecessors dealt with class inequality, Chandler expanded the expressionist political dialogue by dealing in no uncertain terms with racial inequality.51

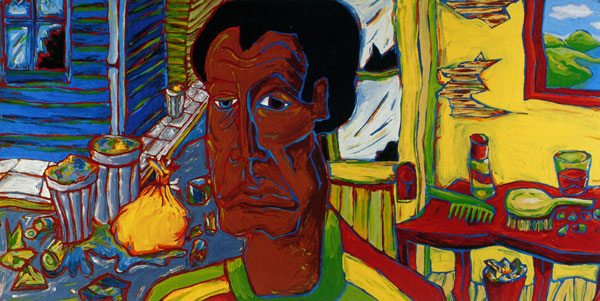

The Ghetto (1980, plate 25)  shows Chandler at the height of his powers and is characteristic of his bold style. This artist has always been concerned with making accessible and clear images with strong emotional impact, and he does this with vibrant colors, stark outlines, and recognizable imagery. Several of his design choices are reminiscent of posters, signage, and propaganda art. But Chandler’s work is never simplistic. In The Ghetto, for example, the clever positioning of the central monumental figure subtly marks a transition between the garbage-strewn street and a crumbling domestic interior, each painted in different scales and with separate senses of spatial illusion. Both indoors and outdoors crowd in on the man, trapping him in his bleak environment. According to the artist, “My job is to depict/report, without hatred or rage, our cancers, self-inflicted or otherwise, point to solutions, and present them to you visually. Not just to paint pretty pictures, though I can do that as well . . . “52

shows Chandler at the height of his powers and is characteristic of his bold style. This artist has always been concerned with making accessible and clear images with strong emotional impact, and he does this with vibrant colors, stark outlines, and recognizable imagery. Several of his design choices are reminiscent of posters, signage, and propaganda art. But Chandler’s work is never simplistic. In The Ghetto, for example, the clever positioning of the central monumental figure subtly marks a transition between the garbage-strewn street and a crumbling domestic interior, each painted in different scales and with separate senses of spatial illusion. Both indoors and outdoors crowd in on the man, trapping him in his bleak environment. According to the artist, “My job is to depict/report, without hatred or rage, our cancers, self-inflicted or otherwise, point to solutions, and present them to you visually. Not just to paint pretty pictures, though I can do that as well . . . “52

Another artist who made a significant contribution to the expressionist sensibility in Boston was Flora Natapoff. Natapoff began her career in New York, where she absorbed the influence of Abstract Expressionist painters, primarily de Kooning. But by the time she came to Boston in 1974 to teach at Harvard University’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts, she had begun to mature artistically and arrive at her own style. For works like Harvard Square, Orange and Green (1982, plate 26) , Natapoff developed a collage technique writ large. She combined torn bits of paper with brushy applications of paint to create ambitious urban and technological landscapes. These works are expressionist in their deliberate formal distortions, and in the artist’s intention to capture the feeling, rather than the look, of the city, its architecture, and its dynamism. And while heavily indebted to a collage technique, they can be confidently considered paintings. As art historian Carl Belz explained, “the fragments of paper are descriptive; they function like a repertory of brushstrokes, each possessing a different shape, edge, or color, depending on the combined requirements of the subject and its image.”53 The twentieth-century collage aesthetic is largely about the juxtaposition of images. In Natapoff’s technique, collage is used like paint to make an overall image coalesce. Although the artist left Boston for London in 1982, she continued to address the theme of the city in her new home and still shows her work in Boston.

, Natapoff developed a collage technique writ large. She combined torn bits of paper with brushy applications of paint to create ambitious urban and technological landscapes. These works are expressionist in their deliberate formal distortions, and in the artist’s intention to capture the feeling, rather than the look, of the city, its architecture, and its dynamism. And while heavily indebted to a collage technique, they can be confidently considered paintings. As art historian Carl Belz explained, “the fragments of paper are descriptive; they function like a repertory of brushstrokes, each possessing a different shape, edge, or color, depending on the combined requirements of the subject and its image.”53 The twentieth-century collage aesthetic is largely about the juxtaposition of images. In Natapoff’s technique, collage is used like paint to make an overall image coalesce. Although the artist left Boston for London in 1982, she continued to address the theme of the city in her new home and still shows her work in Boston.

But the most art historically significant and far-reaching stimulus to the expressionist tradition—both nationally and locally—was the towering figure of Philip Guston. Guston basically had three careers, in the thirties and forties as a Figurative Expressionist with a distinctly political agenda, in the fifties and sixties as an Abstract Expressionist who painted in a lyrical, idiosyncratic style, and after 1970 as a stylistic maverick who became an important progenitor of the Neo-Expressionism that swept the international art scene in the late seventies and early eighties.54

Guston’s maverick days began with his famous October 1970 solo exhibition at New York’s prestigious Marlborough Gallery. The art world expected yet another show of non-objective paintings—gently inflected fields of pink, rose, and gray. But Guston shocked everyone, presenting instead large canvases, painted in a klutzy cartoon style, that featured figures and objects in narrative scenes— all anathema to the prevailing non-objectivity and formalism espoused by critic Clement Greenberg and legions of doctrinaire Minimalists. Moreover, the images were bizarre: piles of shoes, smoking cigarettes, disembodied limbs, and, most famously, figures hooded like Klansmen, racing around in jalopies. The show was panned by stunned critics.” Guston responded: “I got sick and tired of all that purity. I wanted to tell stories.”56

Despite the initially hostile press, Guston continued to paint his stories. And he found refuge from New York brickbats in Boston. Throughout his career, the painter had enjoyed a long and positive relationship with the Boston art world. As early as 1949, while still a Figurative Expressionist, Guston lectured at the Museum School under the auspices of Karl Zerbe. In 1966, he had a major exhibition of his Abstract Expressionist work at The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis, and in the following year he held a public conversation on art with Professor Joseph Ablow at Boston University. Then, in 1970, at the instigation of David Aronson, Guston received an honorary doctorate from the university, which also enthusiastically hosted an exhibition of the painter’s new work shortly after the Marlborough Gallery debacle. In 1972, he became a Visiting Critic, and in 1973 he was appointed University Professor, a post that he held until 1978 (fig. 26). As University Professor, Guston traveled from his home in Woodstock, New York, to meet with students in Boston University’s graduate painting program for intensive three-to four-day stretches. In 1974, he showed another body of new paintings at the university.57

Guston’s time at Boston University meant a great deal to him, both professionally and personally. During a period of great stress, occasioned by continuing carping over his new work by friends and critics in New York, Guston found a faculty, student body, and audience unconstrained by Modernist orthodoxy and genuinely appreciative of Figurative Expressionism. He also gained public recognition, academic justification, and a forum for expounding upon his new ideas. The seventies also proved to be the most fertile decade of Guston’s career, in terms of both sheer output and free artistic experiment and risk-taking. Inside-Outside (1977, plate 27)  is typical of the kind of painting that he made during his time at Boston University. In it appear standard issues from his late iconography: disembodied hairy legs fitted into impossibly flat shoes, a light bulb, a cockroach, bottles and paint tubes, an ashtray— all crazily adrift in a shocking pink artist’s studio. Space, scale, and narrative are all ambiguous. What is the function of the giant looming door, seemingly off its hinges? What really goes on here, in this expressionist allegory of the artist’s creative desires?

is typical of the kind of painting that he made during his time at Boston University. In it appear standard issues from his late iconography: disembodied hairy legs fitted into impossibly flat shoes, a light bulb, a cockroach, bottles and paint tubes, an ashtray— all crazily adrift in a shocking pink artist’s studio. Space, scale, and narrative are all ambiguous. What is the function of the giant looming door, seemingly off its hinges? What really goes on here, in this expressionist allegory of the artist’s creative desires?

Guston just didn’t give a damn any longer about the priorities and protocols of the New York art world, especially in light of all that he saw going on around him. He said:

When the sixties came along I was feeling split, schizophrenic. The war, what was happening to America, the brutality or the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into a frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue. I thought there must be some way I could do something about it. I knew ahead or me a road was laying. A very crude, inchoate road. I wanted to be complete again, as I was when I was a kid. . . . Wanted to be whole between what I thought and what I tell.58

And this is the great legacy that Guston passed on to his students at Boston University. He stressed that painters should follow their own honestly and strongly felt muse. There should be no disjunction between form and feeling, and no difference between deeply personal and potentially universal content. The strict integrity of emotion, expression, and the act of painting was the ultimate goal, the ultimate truth. Jon Imber, one of Guston’s favorite students at Boston University, remembered that “Guston would differentiate between just making art and expressing the thing that is most important to you. … He felt you can learn to make a painting technically, but would ask if you were touching the thing that inspires you. Were you expressing something about humanity? Every line, every gesture, every piece of surface had to mean something.”59 Through these teachings, and by his example, Guston substantially reinvigorated the heritage of Figurative Expressionism in Boston.

Philip Guston in the Boston University Art Gallery, 1975.

Courtesy Boston University Art Gallery

While Guston was teaching at Boston University, something even more profound was taking place in the art world at large, a development that would add volatile fuel to the embers of Boston’s Expressionist fire and also embrace, justify, and acclaim Guston’s radical late works: Neo-Expressionism.60 This international rejection of Minimalism and formalism, also known as New Image, Primary Images, New Wave, Bad Painting, and New Figuration, arose amongst young artists simultaneously, in the late seventies and early eighties, in Germany, Italy, and the United States. A new roster of art stars burst upon the scene, adding considerable excitement and some stylistic cohesion to an art world drifting in the visual doldrums of reductivist non-objective painting, colorless primary structures, anti-visual Conceptual Art, and post-Minimalist exercises that seemed overwhelmingly conditioned by a Minimalist agenda that would just not go away. Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, Jorg Immendorf, Sigmar Polke, and A. R. Penck in Germany; Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, and Enzu Cucchi in Italy; and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Sue Coe, Eric Fischl, and Julian Schnabel in America led a broad-based return to the figure in narrative contexts. Their paintings were huge, raw, deliberately awkward, and riotously colored and composed. In her catalogue for the seminal 1978 Bad Painting exhibition at New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art, Marcia Tucker wrote:

It is figurative work that defies, either deliberately or by virtue of disinterest, the classic canons of good taste, draftsmanship, acceptable source material, rendering, or illusionistic representation. In other words, this is work that avoids the conventions of high art, either in terms of traditional art history or very recent taste or fashion. Nevertheless, “bad” painting emerges from a tradition of iconoclasm, and its romantic and expressionist sensibility links it with diverse past periods of culture and art history.61

There was no mistaking that this new tendency represented a massive resurgence of expressionism. In America, these painters used their arsenal of agitated formal distortions to express feelings about a wide range of humanistic concerns and contemporary anxieties: myth, dreams, personal identity, historical tragedy, natural and technological apocalypse, consumerism, the deleterious effects of the mass media, urban violence, pornography, and other cultural vulgarisms. The Neo-Expressionists consciously bore the influences of German Expressionism, Surrealism, and their own immediate precursors, a group of figurative painters active in the sixties and seventies who had been labeled as “eccentrics”: Guston, Charles Garabedian, Joan Brown, Jim Nutt, Roger Brown, Ed Paschke, and H. C. Westermann. But to this expressionist heritage they added some characteristics that helped define the work of their own generation. Among them were the adoption of vernacular art forms like graffiti and comix, wholesale appropriations from art history and the mass media, and a tendency to overload canvases with dense, layered imagery to reflect the information-saturated culture in which they were immersed.

Artists in Boston were well aware of this phenomenon. The international art press made much ado about Neo-Expressionism, and exhibitions of this hot new style were everywhere. Bostonians traveled to New York to see not only the Bad Painting show but also New Image Painting at the Whitney Museum in 1979, and the 1981 and 1983 Whitney Biennials, which were chock-a-block with huge and savage paintings.62 Even at home there was no dearth of contemporary expressionism on display. In addition to the seventies Guston shows at Boston University, in 1980 The Rose Art Museum at Brandeis organized Aspects of the 70s: Mavericks, which included Figurative Expressionist works by Guston, Garabedian, Leon Golub, Red Grooms, Jess, and Lucas Samaras. In 1983, the Hayden Gallery at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology presented Body Language: Figurative Aspects of Recent Art, and The Institute of Contemporary Art’s Currents series, which ran from 1983 through 1985, brought to town works by Penck, Cucchi, Clemente, Golub, and many others associated with Neo-Expressionism. Even the venerable Museum of Fine Arts got in on the act. In 1986, its round-up of area private collections, Boston Collects: Contemporary Painting and Sculpture, included paintings by Baselitz, Penck, Polke, and Guston (as well as contemporary Boston Neo-Expressionists Gerry Bergstein, Alfonse Borysewicz, and Clifton Peacock).

A new generation of painters in Boston began to don the expressionist mantle. Not only did they represent the local arm of an international movement, they also were the direct inheritors of mid-century Boston Expressionism. Pamela Allara noted, “because during the fifties, the principles of Expressionism were so firmly established at Boston’s universities, it permanently conditioned the cultural climate. Subsequent generations could not avoid absorbing its ideas, even if, because of critical neglect, they were unaware of its art.”63 With Bloom, Zerbe, Aronson, et al., the new expressionists in Boston shared a devotion to the figure, a respect for painterly craft and art historical tradition, and a tendency toward allegory. Formally, the two generations were alike in what critic Theodore Wolff identified as their “particular emphasis on somewhat acidic, profoundly subjective themes fervently articulated within a pictorial context that is often gigantic in scale, blatant or exotic in imagery, and opulent or strident in color.”64 The young painters also employed a device central to the work of both Beckmann and the Surrealist artists whom they also admired: the evocative and irrational juxtaposition of disparate objects in shallow fields. They, too, were humanists, but Allara identified an important distinction in attitude between New York and Boston: “Neo-Expressionism uses the central motif of classical art— the figure—to speak to the death of humanism; whereas, Boston art celebrates its legacy.”65

The work of expressionist artists in Boston around 1980 is difficult to lump together as a singular movement, for each artist pursued his or her own muse with a distinctive style. However, a few general themes emerge that unify these artists and set them apart somewhat from concurrent expressionisms practiced elsewhere. Their content was deeply personal rather than overtly political. They also evinced a deep appreciation of a range of Surrealist images and techniques that could plumb the individual and universal depths of the subconscious. They were not averse to humor, or to reflecting the overwhelming impact of popular culture, which distanced their work from the high seriousness of fifties Boston Expressionism. After all, when Bloom and Levine were boys, they took to art as a refuge from a milieu circumscribed by religious dogmatism, cultural isolation, and poverty. The artists who grew up in postwar America were busy watching The Twilight Zone and Bugs Bunny. But in their later works, beginning in the nineties, they moved slowly away from themes of agitation and the bizarre to embrace subjects—and formal approaches—imbued with dignity, lyricism, and a melancholy peace. And they could paint, really paint, with a mastery of craft and technique that far outshined their New York compatriots.

The first manifestation of a renewal of the local expressionist sensibility was the emergence of several young painters who had studied at area art schools and began showing work in Boston in the late seventies and early eighties. Foremost among them was Gerry Bergstein, who graduated from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 1971 (and began to teach there in 1974). Early on, Bergstein practiced a Surrealism wed to expressionism. Before arriving at the Museum School, he had studied at the Art Students’ League in New York under artist Harry Sternberg, who, according to Bergstein, painted like Jack Levine.66 Then, in Boston, he studied with Henry Schwartz and Jan Cox, a Belgian Surrealist painter who had succeeded Zerbe as head of the Department of Painting and Drawing. Bergstein was also profoundly influenced by the Surrealists Max Ernst and Rene Magritte, Abstract Expressionists de Kooning and Gorky, and, of course, Guston.67

Bergstein distilled all these sources into a personal approach in which Surrealist techniques of free association and irrational juxtaposition were brought to bear on expressively distorted images created with an amazing facility of craft. This artist could draw and paint like an expressionist, an Abstract Expressionist, a veristic Surrealist, and a trompe-l’oeil master—and convincingly combine these styles on a single canvas.68 During the eighties, this stylistic spectrum was matched by an equally diverse range of imagery drawn from art history, self-portraiture, nature, popular culture (especially television), and the suburban cultural landscape—again, all on the same surface.69 A fine example of this visual riot is Bergstein’s Self-Portrait as a Fur Covered Volcano (1983, fig. 27), about which the artist said, “This painting was inspired by a remark from my wife who said I was a ‘fur covered volcano’ in that I often seem placid and soft on the outside while seething on the inside. … I continued to explore the spatial tensions obtained by juxtaposing thick and thin paint. I had always been interested in juxtaposition of images (Magritte). I was finding that juxtapositioning of different surfaces could be just as strange and surreal.”70

The point of Bergstein’s technique and approach to imagery is fundamentally humanistic and expressionistic. He seeks to express ineffable mental states conditioned by his own experience of the world—an admittedly chaotic and confusing world—as a model for emotionally apprehending larger issues in contemporary society, psychology, epistemology, and ontology. These weighty themes, though, are always tempered by humor. As the artist explains it, “My goal is to do for painting what Groucho Marx and Alfred Hitchcock did for movies and television. My work is a representation of the paradoxes, ironies, and absurdities of our media-bombarded culture, translated through the language of paint.”71 Elsewhere he wrote, “I still wonder how the unexplainable creation of the universe, the light-speed movement of all those subatomic particles, and billions of years of evolution could have led to squeezing the Charmin, tax returns, life insurance, the art world, and other strange results. If, as Einstein said, ‘God does not play dice with the universe,’ maybe he was playing bingo.”72

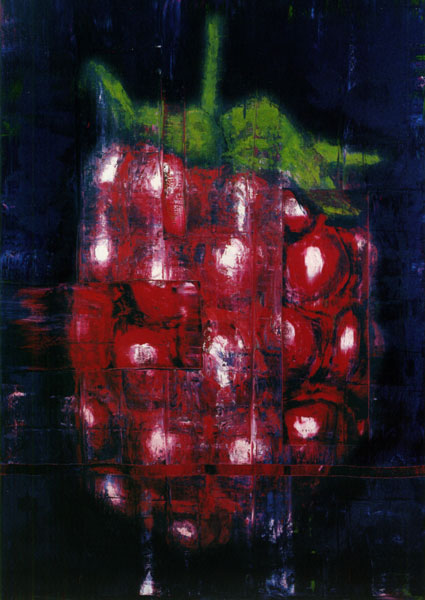

By the nineties, Bergstein’s paintings had calmed considerably. The crashing motion of style and image was replaced by more quiet compositions in which time was apprehended not as manic simultaneity but as a slow falling-away, implied by hushed colors and images of rotting fruits and falling leaves. These paintings, more romantic and less surreal, like “Entropy #4 (1991, plate 28)  , still rely on the artist’s complete control of painting and drawing and also deal with personal/universal humanistic themes: fecundity and barrenness, youth and age, life and death.73 But the artist traded in his idiosyncratic disgorgement of the contents of his gray matter for the time-honored poetic language of decay.

, still rely on the artist’s complete control of painting and drawing and also deal with personal/universal humanistic themes: fecundity and barrenness, youth and age, life and death.73 But the artist traded in his idiosyncratic disgorgement of the contents of his gray matter for the time-honored poetic language of decay.

Another expressionist artist to emerge from the Museum School was Doug Anderson, who blazed upon the scene immediately after his graduation in 1979. Of all the young expressionist painters in Boston, Anderson was subject to the greatest amount of exposure and media hype, most likely because his work resonated so closely with the then very hot Neo-Expressionist developments in New York.74 A savvy art world player, Anderson was well aware of the potential of his cultural context: “I started sliding out of abstraction and was pushed also by the fact that there were a lot of painters around at the end of the 70s who were starting to reincorporate the figure and objective imagery in a very exciting way that had nothing to do with traditional realist figurative work . . . “75

Like his contemporaries in Gotham, Andersen’s work was strident, garish, and violent. His imagery was over the top—nightmarish to the point of paranoia with images of war, urban strife, and disease, yet peppered with whimsy and kitsch. Like Bergstein, he shared an interest in Surrealist juxtaposition, popular culture, and the mass media. And like all the Boston Expressionists since the forties, he was at heart a colorist. He adopted a ferocious style, with overheated hues and paint applied like liquid fire. His slick, intense surfaces were inspired by the look of glossy magazines and served a number of purposes. According to Anderson, “An imperative seems to come across through color—a warning sign or a portent; some of the work seems gaudily religious, but simultaneously rooted in consumer advertising—color functions both as a danger signal and an invitation or attempt at seduction.”76

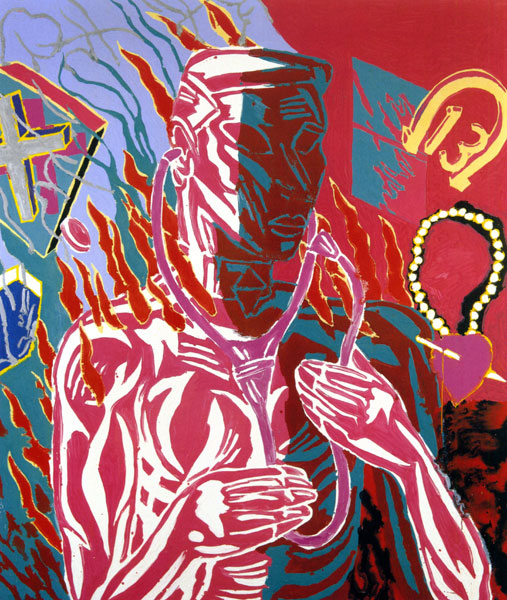

With this signature style, Anderson set up barely cohesive allegories like There’s No Cure Find a Place for It (1982-1983, plate 30).  Here, a flayed and burning central figure speaks into a stethoscope, surrounded by floating superstitious and religious charms. This strange and ambiguous work could be interpreted as a terrifyingly anxious expression of fear, fate, death, and desire at the onset of the AIDS epidemic. Like the work of his colleagues, Andersen’s work calmed down in the nineties and became in turns more decorative and cerebral. Yet, despite his national recognition and local prominence, Anderson stopped painting and by the end of the decade left Boston for California to apply his creative energies to the widening world of the Internet.

Here, a flayed and burning central figure speaks into a stethoscope, surrounded by floating superstitious and religious charms. This strange and ambiguous work could be interpreted as a terrifyingly anxious expression of fear, fate, death, and desire at the onset of the AIDS epidemic. Like the work of his colleagues, Andersen’s work calmed down in the nineties and became in turns more decorative and cerebral. Yet, despite his national recognition and local prominence, Anderson stopped painting and by the end of the decade left Boston for California to apply his creative energies to the widening world of the Internet.

Another artist who started out from the Museum School and eventually left Boston (but not painting) is Alex Grey. For a single year, 1974 to 1975, Grey attended the school, where he pursued performance art of a particularly exhibitionistic and ritualistic variety.77 By the end of this year the artist had two important formative experiences: he met his life and career partner, Allyson, and he dropped acid for the first time. Grey had a predisposition for all things mystical and continued, with Allyson, to take LSD as a spiritual exercise. This hallucinogenic quest for enlightenment came to fruition when the pair unlocked the mystery of what they call the Universal Mind Lattice. Grey explains this as

an advanced level of spirituality beyond the material realm of seemingly separate objects. My wife and I simultaneously experienced this psychedelic transpersonal state in 1976. We lay in bed with blindfolds on, as our shared consciousness, no longer identified with or limited by our physical bodies, was moving at tremendous speed through an inner universe of fantastic chains of imagery, infinitely multiplying in parallel mirrors. At a superorgasmic pitch of speed and bliss, we became individual fountains and drains of light, interlocked with an infinite omnidirectional network of fountains and drains composed of and circulating a brilliant iridescent love energy. We were the Light, and Light was God.78

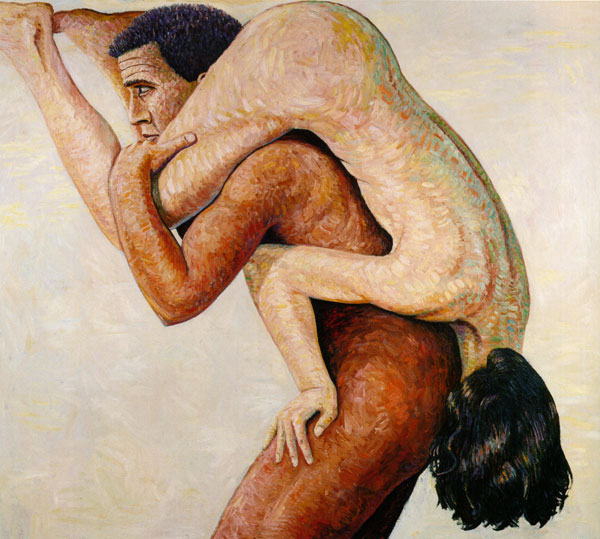

Between 1978 and 1983, when the Greys left Boston for New York, Alex developed a personal style and iconography to communicate the spiritual insights gained from LSD, meditation, and readings from a host of religious and occult texts. In works like Kissing (1983, plate 31) , an allegory of personal and universal love, Grey attempts to provide a visual analogy for the wholeness and unity of physical and spiritual being. He uses a tight academic drawing style that verges on medical illustration to reveal the inner, material workings of the human organism.79 Surrounding and connecting these idealized yet transparent bodies are waves of energy and symbols derived from various mystical traditions that describe the spiritual aspects of existence, and the unity of all things within the Universal Mind Lattice. Grey explained, “I show the physical form as well as other subtle energies. I approach the physical body with a hyper-real approach that then, in a way, seduces the mind into imagining these other disciplines as equally true.”80

, an allegory of personal and universal love, Grey attempts to provide a visual analogy for the wholeness and unity of physical and spiritual being. He uses a tight academic drawing style that verges on medical illustration to reveal the inner, material workings of the human organism.79 Surrounding and connecting these idealized yet transparent bodies are waves of energy and symbols derived from various mystical traditions that describe the spiritual aspects of existence, and the unity of all things within the Universal Mind Lattice. Grey explained, “I show the physical form as well as other subtle energies. I approach the physical body with a hyper-real approach that then, in a way, seduces the mind into imagining these other disciplines as equally true.”80

Grey’s “hyper-real” style, tied to observations and diagrams of anatomy, is a far cry from the painterly physiognomic distortion usually expected from expressionist work. However, he does distort perceptual reality—most radically—and his intentions lie firmly within the ethos of expressionism. His interest in the profound depths of the human condition, and his desire to break down dualities of mind/body, matter/spirit, and the self/other—with their roots in personal transcendent experience—are directly parallel to the aims of Hyman Bloom. 81